After years of dealing with a corruption-ridden Mayor Eric Adams, beleaguered New Yorkers on June 24 selected a mayoral candidate in the Democratic primary—often the city’s de facto general election. While the city’s ranked-choice voting system meant that the official winner won’t be known until July 1, the presumed victor is the top vote-getter in the first round: state assembly member Zorhan Mamdani.

But for much of this election cycle, it has been easy for a casual consumer of news to believe that only one person was in the running to replace Adams: disgraced former New York State Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

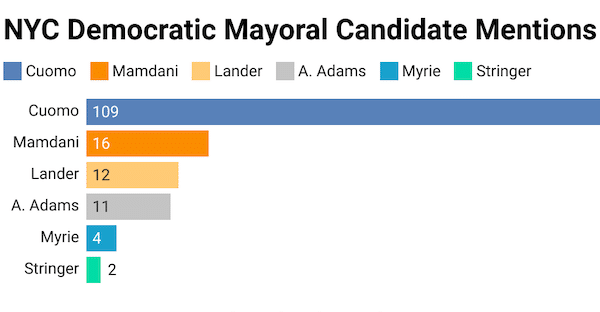

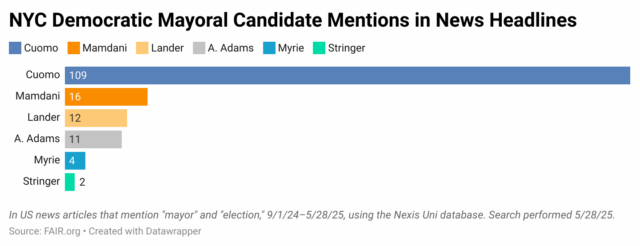

A FAIR analysis of media coverage of the top six Democratic candidates (based on polling through the end of May) found that Cuomo’s name appeared in headlines seven times more often than Zohran Mamdani, who for months had been in second place in opinion polls, and nine times more often than Brad Lander, who typically came in No. 3 in the polls (as he did in first-round voting). The omissions were sometimes egregious; for example, one May 2025 New York Times article (5/17/25) was headlined “Can Cool Kids Get This Mayoral Candidate Elected?” Mamdani was the candidate in question, but his name was relegated to the subhead.

By far the most references

FAIR searched the Nexis Uni news database for U.S. news stories that included each candidate’s name and the words “mayor” and “election.” (We looked on May 28, 2025, going from September 1, 2024, until the date of search.) We then manually filtered out duplicates and false positives. Cuomo received by far the most references, with 411. Lander had the second-most, with 266; Mamdani had only 203.

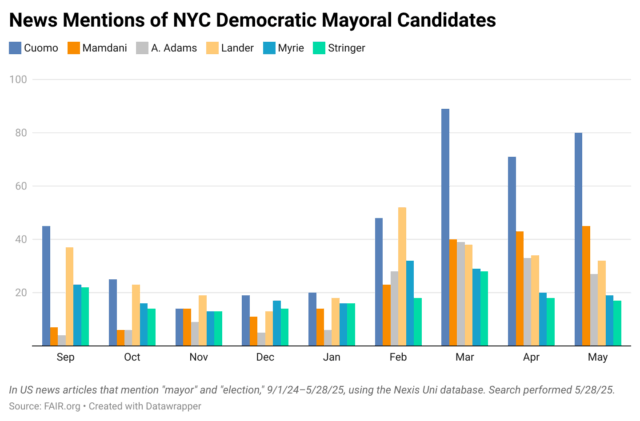

Cuomo’s mentions increased markedly after he announced his candidacy on March 1, but rumors of his candidacy made him the most-mentioned candidate in most of the preceding months.

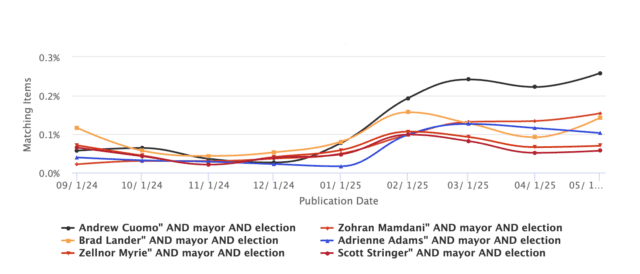

FAIR searched Media Cloud‘s New York state and local news database as well, with similar results: Cuomo became the clear leader in mentions in February, with far greater coverage than his competitors in the three months before the election. Cuomo had 141 mentions in New York media in the month of May, versus 84 for Mamdani and 78 for Lander.

Media Cloud analysis of New York Democratic mayoral primary coverage.

Familiarity creates affinity

Maisie Williams as Arya Stark from Game of Thrones.

To understand why this matters, consider a different name—Arya.

The first time the name Arya appears on the Social Security Administration’s list of most popular baby names is in 2010, where it crawled onto the list as the 942nd-most popular name for girls. That’s the same year that Game of Thrones debuted with a bang, introducing the country to Arya Stark—a main character and a fan favorite. By 2019, when the show fizzled its way off the air, the name Arya had become the 92nd-most popular baby name for girls in the country.

Despite the truism that familiarity breeds contempt, familiarity can in fact create affinity, according to Kentaro Fukumoto, a professor of political science at the University of Tokyo.

“In psychology, there’s a theory called the mere exposure effect,” Fukumoto told FAIR. “The theory argues that when you’re exposed to something [enough] you start to like it.”

Mere exposure effect is how one goes from not even knowing the name Arya to deciding to name your child Arya. It’s also how we sometimes go from hating a song on the radio to loving it. And it’s why companies—and politicians—run ads. The hope is that if we hear a name often enough, it will unconsciously motivate us to buy the product or vote for the candidate. And there’s some evidence, at least when it comes to politicians, that they’re right.

Name-recognition effect

Campaigns use lawn signs in part to increase the familiarity of their candidates’ names (Creative Commons photo: Eric Behrens).

In 2018, Fukumoto published a study that looked at what happened in Japanese elections when a Japanese national candidate shared a last name with a candidate in a down-ballot race—and thus voters were exposed to that name a lot. Fukumoto found that in districts where candidates shared a name, the national candidate received a 69% boost, compared to how they performed in districts where they didn’t share a name. So, for example, if a national candidate had 10% of the vote share, in districts where they shared a name with a down-ballot candidate, their vote share would become 17% —a sizable jump.

Fukumoto cautions that for major candidates, the effect is likely not as large, but the effect is very important for minor candidates—say, a lesser-known candidate challenging an incumbent. In the New York City mayoral race, Mamdani and the other less-covered candidates certainly were much less well-known than Cuomo, who not only served as governor, but whose father also served as governor from 1983—94.

A 2013 study by researchers at Vanderbilt University also found that name recognition can give candidates a boost. That study took advantage of the fact that a local school had strict routes for parents to drive down, to avoid creating the dreaded overburdened school pick-up line. The researchers placed four lawn signs for a local election with a fictional candidate—Ben Griffin—along one of the routes, and then surveyed all of the parents afterwards. They found that parents who drove along the route with the sign were 10 percentage points more likely than those who didn’t drive along the route to say that they would put Griffin—who, remember, did not exist—in their top three choices for a council seat. And that’s a handful of lawn signs placed along one road.

In aggregate, news outlets prioritizing one candidate over others could shift the outcome of the election. When one considers that the 2021 mayoral primary election was decided by just 7,000 votes, it matters that Lander received roughly 35% less attention, Mamdani 50% less attention, and Adrienne Adams, the speaker of the New York City Council (and no relationship to Eric Adams), received 62% less coverage than Cuomo.

Bad publicity still publicity

Some of Cuomo’s coverage may have related to his history of scandals (New Republic, 1/26/24)—but a FAIR analysis (4/9/25) found media downplayed that record.

Some of Cuomo’s mentions were likely tied to the continued fallout of his governorship, including his concealment of nursing home deaths during the Covid-19 pandemic, and lawsuits tied to the New York attorney general’s report on complaints that he had sexually harassed employees. That report affirmed that Cuomo had sexually harassed members of his own staff as well as other state employees, creating a culture “filled with fear and intimidation.”

But at the same time, many of the candidates in the race were current government officials, who might be expected to generate news coverage in the course of their work. Adrienne Adams has been the speaker of the New York City Council since 2022. Lander is the city’s current comptroller, widely considered the second most powerful citywide office, serving as the chief financial officer and auditor of the city agencies. Mamdani is a New York State Assembly member, and Zellnor Myrie is a New York State senator.

And negative news coverage doesn’t mean negative election impact for candidates receiving outsize media attention—Donald Trump famously received billions of dollars worth of free media in his 2016 campaign, much of it negative.

Thumbs on the scale

Further, while the analysis focused on the frequency of occurrences, not the tone, in recent weeks some news outlets have made their support for Cuomo more explicit. The New York Times editorial board said in 2024 that it would no longer endorse candidates for local races, but still this week published a confusingly written piece (6/16/25) that amounted to an endorsement for the former governor. (In April, a FAIR analysis—4/9/25—found the Times’ coverage of the former governor’s record notably forgiving.)

The Atlantic‘s Annie Lowrey (6/12/25) noted that “the political scion with a multimillion-dollar war chest and blanket name recognition could lose to the young Millennial whom few New Yorkers had heard of as of last year”—before going on to argue that “if this is democracy, it’s a funny form of it.”

Similarly, Annie Lowrey in the Atlantic (6/12/25) wrote a piece, rife with inaccuracies about voting methods, criticizing the city’s system for primaries as anti-democratic. New York City uses a ranked-choice system, which allows voters to rank mayoral candidates in their order of preference. While mathematicians don’t all agree on which voting systems are the best at accurately capturing voter preferences, there is broad consensus that plurality voting—where the candidate who gets the most votes in a single round wins—is the worst. Like the New York Times editorial, Lowrey’s article ends up as a de facto endorsement for the former governor, but by criticizing the system, it also acts to undermine the election itself. In other words, if Cuomo loses under this system—according to Lowrey—no he didn’t.

It’s unsettling that news outlets that proclaim to be for democracy are putting their thumbs on the scale, providing Cuomo with extensive coverage even as he mostly avoided actually meeting the people he has said he wants to govern.

However, while name recognition is important, news coverage is not the only way to get it. In 2018, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez unseated Joe Crowley, a Democrat who had served as the U.S. representative for New York’s 14th District for almost two decades, and received almost no media attention before she did so. She did it, in part, by knocking on doors.

Mamdani, who entered the race in the low single digits as a relatively unknown assemblymember, and headed into Primary Day neck and neck with Cuomo in polling, pledged to knock on at least 1 million doors before NYC’s June 24 Democratic primary. Two weeks ago, on TikTok, Mamdani said they were on track to reach that goal 10 days early.

Kendra Pierre-Louis is an award winning journalist with a focus on climate change and media criticism.