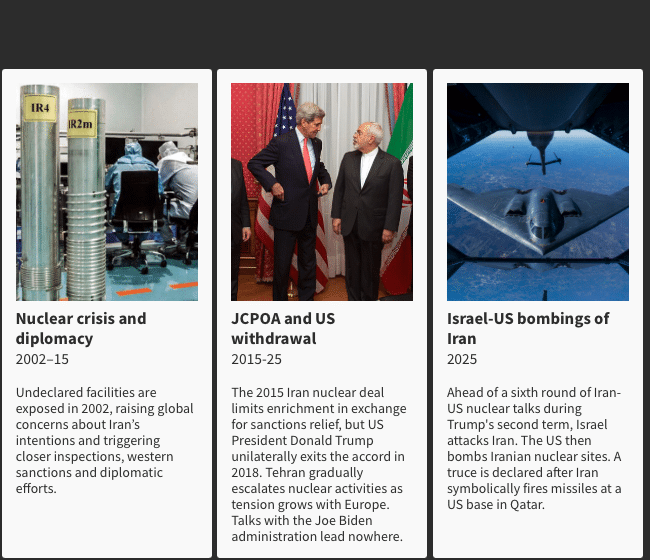

Donald Trump undermined the nuclear architecture when he decided to withdraw the United States from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018. That decision, the hesitations of the Joe Biden administration, and Iran’s refusal to agree to a new deal in the summer of 2022 rendered the JCPOA irretrievable. But the June 21, 2025 attack goes far beyond that. The traditional “maximum pressure” policy has now culminated in an attempt to physically destroy Iran’s nuclear facilities. But what has actually been destroyed is nuclear diplomacy itself.

To grasp the magnitude of this shift, it is necessary to recall the essence of the JCPOA. From their inception two decades ago, nuclear negotiations were based on a simple quid pro quo: Iran would agree to limit its nuclear program and submit it to a strict international verification regime; in exchange, the international community would lift the economic sanctions, initially imposed by the United Nations Security Council back in 2006.

This balance, ultimately enshrined in 2015 with the JCPOA, worked. It allowed Iran to maintain a nuclear program that could only be used for civilian purposes, given the technical specifications of the agreement, and subjected it to constant supervision by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). In return, Iran could reintegrate into international trade and access financing.

Even if it does not formally withdraw from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), Tehran’s political will to accept inspections of its nuclear facilities has vanished.

Clearly, such a negotiation required an exact understanding of Iran’s nuclear capabilities—what is called the baseline—established by the IAEA. In other words, knowing precisely what Iran had, what it was doing, and where. Only with that knowledge could meaningful negotiations take place. It was also the basis for measuring progress, deviations, or violations. The U.S. bombing of Iranian nuclear facilities has shattered this possibility. Even if Iran does not withdraw from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), the political will in Tehran to accept inspections of its nuclear sites—or what remains of them—has evaporated. What we once called nuclear diplomacy with Iran, which the second Trump administration invoked almost until the day of the bombing, has simply died because the foundations on which it was built have disappeared.

What, then, are those who still call on Iran to “return to the negotiating table” talking about? All of us who have participated in nuclear negotiations with Iran are aware of one reality. Quantitative limits could be set: how many centrifuges, how much enriched uranium, and up to what level enrichment could occur—reversing steps Iran had taken in recent years. But what could not be undone was the knowledge acquired by Iranian nuclear scientists and engineers—often the target of Israeli targeted assassinations. This truth was painfully evident for those of us who negotiated from 2021 to 2022, and again in 2024 with the new Iranian government, even more than for those who negotiated from 2013 to 2015—and much more than for those who began negotiations in 2005.

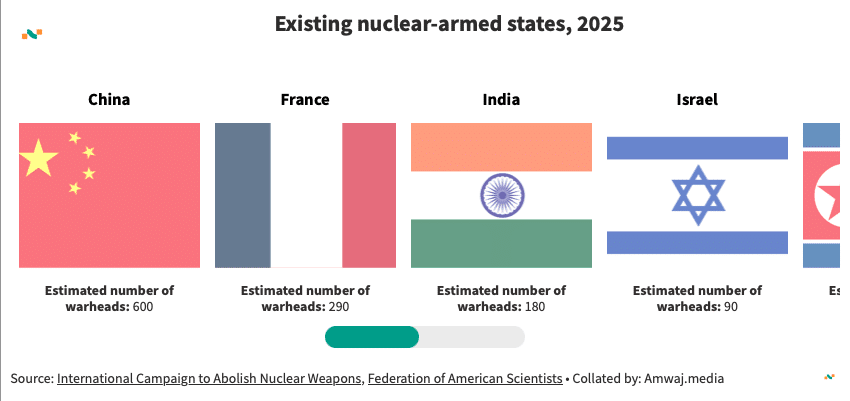

Iranian engineers now master the entire nuclear fuel cycle. They have also developed missiles and delivery systems with domestic technology. These are two of the three necessary conditions for a country to build a nuclear weapon. The third—so-called weaponization, the capacity to miniaturize and mount an explosive device on an operational warhead—has not, according to U.S. intelligence, been developed; Trump does not need to lie like George W. Bush did. But this is not an insurmountable technical barrier. It is a matter of time and political will.

This is where the June 21 attack may have been decisive. Never before had the United States directly attacked Iranian territory. This unprecedented strike has shown the Islamic regime, for the second time, that nuclear diplomacy is reversible, fragile, and vulnerable to changes in leadership in Washington. There will not be a third time.

Returning to the earlier question: what are France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and others talking about when they call for a return to negotiations? They are not referring to what was buried and destroyed in Fordow or Natanz, but to what is buried and alive in the minds of Iranian engineers. The deal now would involve Iran committing not to develop a nuclear program, even for civilian purposes, in exchange for the lifting of economic sanctions. Is it realistic to expect Iran to make that commitment? And for the United States to reward it by lifting sanctions? Washington has always had major difficulties securing Senate approval to lift sanctions in exchange for tangible steps such as dismantling centrifuges or shipping enriched uranium out of Iran. It seems unreasonable to expect it to lift sanctions in return for a mere promise—a piece of paper on which the Islamic Republic states it “will not do it anymore,” perhaps accompanied by a few symbolic transparency measures.

If such a deal lacks meaning from the American side, it sounds like a macabre joke from the Iranian perspective—except perhaps tactically, to stop Israeli strikes. It is inconceivable that Iran would commit to not developing nuclear activities while nearly all Gulf Arab states are doing so—and while under the threat of bombs. No, nuclear diplomacy is dead.

If Iran now chooses to take that third step—the militarization of its nuclear capabilities—if it now decides to move toward a bomb, it will do so following a clear strategic logic: no one bombs the capital of a nuclear-armed country. June 21, 2025, may go down in history not as the day the Iranian nuclear program was destroyed, but as the day a nuclear Iran was irreversibly born.

A Spanish version of this article was originally published on the website of the Spanish magazine Politica Exterior.