In one of the most enduring axioms of revolutionary integrity, Amílcar Cabral—African liberation theorist, freedom fighter, and martyr—urged those engaged in the struggle for liberation and justice to “Tell no lies, claim no easy victories.” This precept demands truth-telling, humility, and a relentless confrontation with reality. It stands in opposition to demagoguery, denial, and the temptation to obscure difficult truths for the sake of appearances.

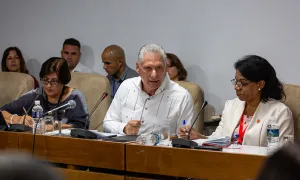

In today’s Cuba, as the country grapples with the profound effects of the U.S. economic war and internal social challenges, President Miguel Díaz-Canel’s recent statements, countering previous incongruous (to say the least) remarks of a now-resigned government minister on inequality and social vulnerability, reaffirm the Cuban Revolution’s commitment to Cabral’s principle. Far from concealing its difficulties, the Revolution has chosen the path of honesty, ethics, and humanism—a path that is difficult but principled.

The U.S. economic siege against Cuba is not merely an attempt to destabilize the country’s economy; it is a deliberate strategy of suffocation. It aims to incite internal discontent, distort the image of the Cuban government, and ultimately dismantle the gains of the Cuban Revolution. This is a war of attrition, conducted not only with financial sanctions and trade restrictions but also with a barrage of misinformation and psychological warfare. In this climate, any misstep by the Cuban government or deficiency within Cuban society is exaggerated and weaponized. As a result, flaws that are inherent to every political and economic system—especially under duress—are made to appear as unique failures of socialism. Yet these are not signs of ideological collapse, but rather indicators of how relentlessly the Revolution is attacked.

Despite this unrelenting pressure, the Cuban revolutionary leadership continues to engage in a critical self-assessment. In his remarks to the National Assembly’s Commission on Youth, Children, and Women’s Equality, President Díaz-Canel does not shy away from acknowledging that the country faces serious challenges: from economic distortions and worsening inequality to social behaviours that reflect a breakdown in social, communal and familial bonds. However, instead of denial or scapegoating, he calls for solutions rooted in ethics and justice. “The Revolution does not hide its problems,” he declared.

It faces them with ethics and social justice, even in the midst of extreme circumstances.

This frankness is not weakness—it is revolutionary strength. It is precisely what Cabral called for: an unflinching honesty that does not minimize hardship but also does not abandon hope. Díaz-Canel’s insistence that these are “our problems”—our homeless, our vulnerable communities, our social inequalities—is a testament to the Revolution’s enduring humanistic vocation. This is not a government that disowns the marginalized; it embraces its duty to them. There is a recognition that vulnerability is not an aberration in a revolutionary society but a consequence of both internal and external pressures, and therefore demands coordinated, compassionate, and persistent action.

“These are our problems—our homeless, our vulnerable communities, our social inequalities,” President Díaz-Canel

The Cuban president’s ethical framing of politics echoes another foundational insight of Cabral: that revolutionary struggle is not merely about material gains, but about dignity, truth, and values. Díaz-Canel invoked Cuban revolutionary intellectual Armando Hart to emphasize that “law as an expression of social justice” and “ethics as an expression of truth” must guide the Revolution. In doing so, he rebukes superficial or callous analyses of Cuba’s social difficulties. He cautions against arrogance and detachment, calling instead for “sensitivity,” “human warmth,” and “decent conduct” in addressing the country’s deepest social wounds.

To that end, the Revolution has launched more than thirty targeted social programs, aimed at alleviating the conditions of vulnerable populations. These are not symbolic gestures but material commitments, funded despite the crushing weight of a blockade that seeks to deny Cuba even the basic resources required for governance. The existence of these programs—backed by political will, ethical clarity, and popular participation—demonstrates that the Revolution has not given up on its foundational promises. It continues to strive, in extremely difficult conditions, towards a society where no one is left behind.

What makes Cuba’s stance particularly powerful is its refusal to claim easy victories. It would be tempting, especially under siege, to project an image of success unmarred by crisis. But the Revolution refuses such self-congratulatory illusions. As Díaz-Canel states, “We know our problems have worsened… But the Revolution recognizes that there are causes that have led to these types of problems, and so the Revolution has to… project how we are going to solve it, knowing that it’s a long struggle.” The acknowledgment that progress will be slow and uneven, that not all problems can be solved at once, is a testament to revolutionary maturity—not defeatism.

This political and moral clarity is all the more significant given the dehumanizing narratives promoted by imperialist and monopoly media, which seek to portray Cuba as a failed state. Against this chorus of cynicism, the Cuban Revolution asserts a different truth: that a people who are honest about their difficulties, who remain committed to justice in the face of adversity, and who maintain solidarity as a guiding principle, are not defeated.

To persevere and continue to develop under siege, to continue building a society rooted in dignity, equality, and ethics despite scarcity and external aggression, is not a failure. It is a revolutionary achievement. Thus, the Cuban Revolution remains faithful to Cabral’s injunction—not only in its refusal to lie or claim easy victories, but in its continuing effort to struggle, to confront, and to care.

As Cuba endures an ongoing economic war designed to destroy the capacity of the Cuban government to fulfill its promises and commitments to the Cuban people and erode the island nation’s social fabric, it has chosen the harder but more principled path. It faces its problems squarely, acknowledges its shortcomings, and seeks solutions through collective action and moral responsibility. This commitment to revolutionary ethics and humanism is perhaps the most powerful proof that the Cuban Revolution, despite what some might consider insurmountable odds, remains alive, dignified, and revolutionary.

Honouring Amílcar Cabral’s timeless words, shows the world what it means to fight for justice and genuine emancipation with honesty, courage, and resolve.

Isaac Saney is a Cuba and Black studies professor and historian at Dalhousie University.