The present being a product of the past, our attempt to understand history is a part of our endeavor to understand ourselves and shape our world today. However, it is also true that often our understanding of the present determines the way we look at history. So, when it is popular imagination that is involved in this engagement with history, it can afford an insight into some of the dominant ways in which our social existence is being understood and redesigned.

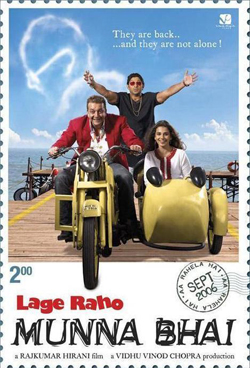

Rang De Basanti Director Rakeysh Mehra. Screenplay Renzil D’Silva & Rakeysh Mehra Music A.R. Rehman Producer Rakeysh Mehra With Amir Khan, Sidharth Suryanarayan, Sharman Joshi, Kunal Kapoor, Atul Kulkarni, Soha Ali Khan, Madhavan, Alice Patten

|

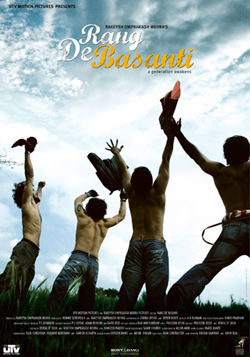

Rang De Basanti [Color it Yellow] — A Generation Awakens and Lage Raho Munnabhai [Carry on Munnabhai], two films released this year to considerable popular acclaim, were also this year’s Oscar contenders. Rang de Basanti was the official entry from India while the producers of Lage Raho Munnabhai had the confidence of popular support to enter it as a private contestant. But it is not Oscar dreams (now dashed) alone that these films have in common. The films have been considered together by commentators because both of them engage with “characters” from another narrative, that of the freedom struggle. Rang De Basanti recruits Bhagat Singh, the young revolutionary who was hanged by the British at the age of 23, while Lage Raho Munnabhai calls upon Mahatma Gandhi, the leader of the national movement for independence. In recent years, filmmakers have again and again visited the site of the freedom struggle and brought to screen the events and personalities associated with that moment. What make these most recent attempts different from the earlier ones is that both the films are located squarely in the present with contemporary characters who are inspired by Bhagat Singh and Mahatma Gandhi respectively. Thus there is an obvious effort at interpreting the words and actions of these figures from the past in the context of contemporary reality

Bhagat Singh, a young revolutionary, was influenced by the Russian revolution and Communist ideology. He and his comrade Batukeshwar Dutt were tried for throwing bombs in the assembly. The bombs were only meant to make a noise with the aim of drawing attention to and protest against the passing of two bills — the Trade Dispute bill and the Public Safety bill — that would severely curtail the rights of workers to strike and protest. After throwing the bombs, they stood their ground distributing pamphlets and courted arrest. In the course of this trial, Bhagat Singh’s involvement in the murder of Saunders, a British officer, was revealed, and he was hanged, along with his comrades Sukhdeo and Rajguru. Mahatma Gandhi, the leader of the Congress Party that was at the forefront of the struggle for independence, inspired a generation with his ideas and practice of non-violence as a tool of resistance to the British rule. Popular imagination has often perceived these two figures as opposites, without fully understanding their real ideological differences. During the last few decades, with the ascendancy of militant Hindu Right, Gandhi’s politics of non-violence and Satyagraha (insistence on truth) has increasingly come under disrepute as effeminate, and Bhagat Singh’s young passion divested of its ideological moorings has been seen as a manly antidote. In short, regrettably, a simple dichotomy of violence and non-violence has become popularly equated with the difference between these two. Therefore, the fact that both Rang de Basanti and Lage Raho Munnabhai were enthusiastically received by the same audience despite the two films apparently containing opposed messages is surprising and reason to look closely at the “messages” and their politics.

The pre-release publicity of Rakyesh Mehra’s Rang de Basanti — A Generation Awakens had hinted at the theme of youth as architects of change. The film traces the transformation of a gang of friends from carefree, bohemian, disillusioned “good for nothings” to people who sacrifice their lives for a cause. This transformation is the result of their participation as actors in a film on the life of Bhagat Singh. Sue (Alice Patten), an English girl, comes to India to make a documentary on the lives of the Indian revolutionaries with a script based on a diary kept by her grandfather James McHeneley, who served as a superintendent in a jail where Bhagat Singh and his comrades were imprisoned. After initial resistance, (the result of their inability to understand or identify with Bhagat Singh’s commitment), the youngsters agree to play the characters in Sue’s film mainly because Daljeet or DJ (Amir Khan) has taken a fancy to Sue and is able to convince his friends. DJ himself plays Chandrashekar Azad, while Karan Singhania (Sidharth Suryanarayan), an alienated son of his rich industrialist father, plays Bhagat Singh, Aslam (Kunal Kapoor) plays Ashfaqullah Khan, Sukhi (Sharman Joshi) plays Rajguru, Laxman Pande (Atul Kulkarni) plays Ramprasad Bismil, and Sonia (Soha Ali Khan) plays Durga Bhabi. Throughout the film, Sue’s documentary (which is nothing like a documentary she claims to be making but a regular fictionalized feature) inter-cuts with the main story line of DJ and his friends and is distinguished from it by its sepia tones, thus continually juxtaposing the present-day Indian youth with the young revolutionaries of the past.

One of the achievements of the film is the near natural portrayal of these youngsters. “College life” has been a perennial theme of Popular Hindi cinema. In a society where only 6.4% of the young people who are eligible for higher education actually have access to it, the college campus naturally becomes a dream site of privilege, freedom, and possibilities. And films have exploited the context of a college campus as a space where romance blossoms between the hero and the heroine. As such, for decades, a set formula consisting of pranks against teachers and others, rival gangs, initial hostility and competitiveness between the main protagonists, and the song and dance through which the hero pursues/woos/threatens the heroine came to define this “boy meets girl” scenario in numerous film. In recent years, these campuses have acquired a designer sheen (Kuch Kuch Hota Hai) or have altogether shifted abroad (Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gum). Rang De Basanti, breaking from this formula that has been so predictable in its artificiality, takes a refreshing look at the life style, values, and concerns of a section of young Indians. This break is possibly also a sign of the Hollywood style narration slowly inching its way into mainstream Indian cinema. There are no classrooms because no one attends class; there are songs, but they are either played on the record player as the “students” dance crazily to the music or used as background scores; there are spontaneous humor and tremendous raw energy of the youth language — slang, abuses, and jokes — which approximates what may be spoken by footloose youngsters in the north of India. That the film’s depiction of youth in its element made identification easy, thus attracting the young audience to the film, is obvious. It is the significance of this identification that is problematic.

A large early portion of the film is given to the making of Sue’s documentary as the friends, reluctantly and irreverently, participate in the enterprise. What also emerges is a certain picture of the young as disillusioned but not particularly bothered by what they see around them. India for them is a corrupt and overpopulated country where people are helpless to do anything about their problem. The only exception is Laxman Pande. Initially, he does not belong to the group and in fact despises these boys and girls for their Western lifestyle and even disrupts their parties. He belongs to the youth wing of a political party, and the saffron scarf around his neck and his derogatory remarks about Muslims directed against Aslam establish his allegiance to the ideology of the Hindu Right. But Laxman is also idealistic and gradually gets drawn to the film-making process and soon starts acting in it although always holding himself aloof until the events that give a major twist to the plot. Sonia’s fiancé Ajay Rathod (Madhavan), who is a pilot in the Indian Air Force, dies in a Mig–21 crash. It becomes evident that inferior spare parts and corruption in the services are responsible for the crash. The Defense Minister, instead of inquiring into the corruption charges, blames the pilot for rash flying. The group leads a peaceful protest that is brutally attacked by the state police machinery. Replicating the revolutionaries’ murder of Saunders, the group murders the Defense Minister and then takes over the radio station to explain their actions to the nation. Commandoes are called in, and DJ, Karan, Sukhi, Aslam, and Laxman die, smiling valiantly. Finally, they have acted; they are not impotent!

A well-made film in terms of script, acting, and visual style, what does Rang de Basanti say? Hundreds of college-going young people take their education and career seriously, become doctors, engineers, and computer programmers, join the military, the police force, or the Indian Administrative Service (IAS). A few youngsters, for various complex social and psychological reasons, remain outside the gambit of this social-integration machine. So are the characters in this film — they are misfits and refuse to buy the promise of the system. For example, DJ graduated from the university five years ago but continues to hang onto the campus because he knows that, while he is respected there, outside he has no role or identity. Karan refuses the advice of his rich businessman father to make something of his life, Aslam spurns the narrow Muslim identity offered by his family, and in the end Laxman sees through the politics of convenience practiced by the Hinduist Party to which he belongs. Potentially this is a group of youngsters whom Bhagat Singh could have spoken to and made half of them converts to his politics. But Bhagat Singh is never allowed to speak to them. The Bhagat Singh of Mehra’s imagination, mediated through the diary of an English jailer and his granddaughter, is only a hotheaded patriot who willingly sacrificed his life for his country. Nowhere do we hear about his ideas on religion, imperialism, exploitation, oppression, or Socialism. And Bhagat Singh was a prolific writer. He died so young, and yet in his letters, diaries, pamphlets, and booklets, his ideas of a just equitable society found ample expression. He even wrote a booklet titled WhyI Am an Atheist while in jail. As a matter of fact, Bhagat Singh had much to say to students, too. At one point, while allowing their concern for education and career, he said that they should also be ready when the time came to move beyond self-interest and give themselves to a larger struggle! However, Bhagat Singh and his comrades in Mehra’s picture are exactly like the ones we have encountered in our school textbooks. The fictional Mr. McHeneley has after all seen only the courage of the young revolutionaries in the face of death and is naturally clueless about what gave them this courage. So, Mehra’s revolutionaries are only fiery-eyed young men of action, sans thought, sans ideas. Consequently, Rang de Basanti merely succeeds in effectively silencing Bhagat Singh.

Not surprisingly, we see no gradual transformation of DJ and his group of friends. They do not notice that farmers, tribals, and workers are daily protesting and struggling to protect their livelihoods from an onslaught of the state and private corporations. They do not become aware of the deep divide in the country between the handful rich and the poor majority. We see only Laxman Pande, the Hinduist student leader, gradually changing as his hardcore Muslim hatred gives way to a more sympathetic identification with the “other.” But the rest continue to have a ball as they shoot the film and occasionally rail against corruption and people’s impotency to do anything about it. The only rejoinder to them is in the form of Ajay Rathod, who claims that he is in the Indian Air Force because he loves his country and would sacrifice his life for it. Indeed, on those rare occasions when they do discuss the problems besetting the country and the solutions to them, it is always in terms of dying for your country by joining the military! Thus it is only with Ajay’s death, that is, when they get a personal blow, that they wake up to prove to the world that the youth will not take things lying down any more!

But, what according to the film is the way forward for the young of India? The answer is to be found in Karan Singhania’s dialogue with the nation. When the boys take over the radio station, Karan takes the mike to declare that they are not terrorists but only students from the university, frustrated with corruption. A question and answer session ensues, and in an answer to a question regarding the possible choices before the young of India, he advises them to join the Military, the Police force, and the Indian Administrative Services! Precisely what numerous students do anyway and what a few like these youngsters did not. It should be noted that he does not advocate struggle or protest, violent or otherwise. That, minutes after this message, Karan and his friends fall to bullets fired by commandoes summoned by the State is an irony evidently unintended by Mehra.

If in Rang De Basanti innocuous college youngsters make a violent choice, then in Rajkumar Hirani’s Bollywood comedy Lage Raho Munnabhai, Munnabhai (Sanjay Dutt) and his sidekick Circuit (Arshad Varsi), the pair of hoodlums made famous by the hugely popular Munnabhai MBBS (2003), become advocates of a version of Gandhian non-violence. Munnabhai falls in love with a radio jockey, Jhanvi (Vidya Balan). In order to meet her, he must win a quiz on Gandhi, which is well nigh impossible because of his supreme ignorance about Gandhi. He asks Circuit the relevance of 2 October (Gandhi’s birthday, which is a national holiday), and Circuit answers that that it’s a “dry day” (a day when liquor is not sold)! Even so, he wins the quiz with the help of Circuit and by kidnapping and bullying certain history teachers into telling him the right answers. To Jhanvi, he pretends that he is a professor and wishes to propagate Gandhianism among the youth by using the tapori lingo (the street Hindi spoken by the lumpen in Mumbai, perhaps a Bollywood construct). When Jhanvi invites him to speak to a group of elderly men living with her grandfather and herself because their children have abandoned them, Munnabhai is in trouble and has to make an attempt to know something about Gandhi. After reading for three days and nights in a library dedicated to Gandhi’s life and works, Gandhi appears to Munnabhai. Henceforth, Gandhi (played by Dilip Prabhavalkar) becomes a mentor to the hallucinating Munnabhai, counseling him and prompting answers to questions people ask him, not only during his visit to Janhvi’s geriatric family but also later when, with Jhanvi, he starts advising people about their everyday problems from her radio studio, becoming a kind of agony aunt.

Lage Raho Munnabhai, which has been applauded for making Mahatma Gandhi hip, is a funny film and through its humor occasionally manages to strike at some of the evils plaguing our social existence, most notably, corruption, superstition, and incivility. That this critique is light-hearted is also the reason why the humor is never black and why the mantra of “Gandhigiri,” which emerges as the message of the film, is a simplistic solution to our problems. “Gandhigiri,” an obvious foil to the “Gundagiri” (hooliganism) practiced earlier by Munnabhai and Circuit, advocates truth and non-violent means of changing the adversary’s heart. Thus, Lucky Singh (Boman Irani), an unscrupulous businessman, who has grabbed Janhvi’s and her extended family’s home, is to be prevailed upon by sending him flowers and get-well-soon cards; a young boy is advised to tell the truth to his father about his misadventures with stocks; and an old former teacher must shame the clerk into releasing his pension by stripping to his underwear in front of the whole office and handing over his little belongings — his watch, glasses, shoes, etc. — to the clerk to make up the sum of the bribe demanded. This packaging of Gandhianism in an easy “usable” formula has been rightly criticized for commodifying a complex socio-political vision. Simple repeatability is essential to branding, and Lage Raho, which is already using the “Munnabhai” brand, creates a new brand “Gandhigiri” by turning “truth and non-violence” into the catchphrase for the brand promising a quick fix for any problem.

Lage Raho Munnabhai’s “Gandhigiri” as propagated by a pair of goons, whose physical prowess is never in doubt, resonates with “Gundagiri” and goes some way in legitimizing a gentler form of resistance. Thus the Hindu Right’s charge of the weakness and effeminacy implicit in Gandhian methods is, in a manner of speaking, answered. Rang De Basanti also articulates disenchantment with the Hindu Right, through the disillusionment of Laxman Pande. The last few years have been witness to a setback in the political fortunes of Hinduist and extreme right-wing parties, and the popularity of both these films echo this mood. While this is essentially welcome, what seeks to replace the lure of a communal identity is possibly a promise of a new lifestyle held out by these films.

Lage Raho Munnabhai differs from Rang de Basanti in that, unlike the latter’s absolute erasure of Bhagat Singh’s politics, Lage Raho Munnabhai‘s interpretation of Gandhi merely simplifies. And yet the understanding of the present that fuels both these interpretations reveals their essential similarity. The chief problem faced by the characters in these films is corruption and fraud in which the state is complicit, in the form of the Chief Minister in Rang de Basanti and petty officials in Lage Raho Munnabhai. That corruption truly plagues individuals and institutions across regions and classes cannot be denied. At the same time, it must be noted that corruption is the major problem discussed by the ideologues of neo-liberalization who see it as a hurdle in the efficient working of market policies. And yet, when thousands of farmers commit suicide, they do so not because of corruption but because of the too efficient implementation of neo-liberal policies. In other words, in making corruption the central dilemma, both the films express the “angst” of the upwardly mobile urban Indians. Both Bhagat Singh and Gandhi, despite their dissimilar ideologies, are recruited for the same cause, that of cleaning up the system without fundamentally recognizing or questioning the real malaise. Consequently, Bhagat Singh’s transformative politics is unnecessary, while Gandhi’s non-violence comes in handy merely to teach people manners: “do not spit in public corners,” “be polite to the lower classes,” etc. To be sure, along with corruption, Lage Raho Munnabhai also communicates, however light-heartedly, the family disconnect that people experience resulting from increasing individualism and competitiveness. Nevertheless, the film’s solution of flowers, gifts, and cards only endorses, once again, the promise of a consumer haven.

The massive transformation in economic and cultural lives of the people in face of the onslaught of global capital has visibly increased and hardened divisions along the axes of caste, gender, and class. In such a context, while the very poor are being almost pushed out of existence, others, like criminals or students who resist integration into the system, exist on the periphery, with immense disruptive potential of one kind or other. When the popular media seek to understand the pressures, conflicts, struggles, and discontents in a rapidly changing world, in their tragic or comic aspect, it is often through the medium of these outsiders, as in the case of these two films. Bhagat Singh and Mahatma Gandhi are interpreted neither through the medium of those who belong — business leaders and IT professionals — nor through those who see the neo-liberal agenda for what it is and are consciously active in resisting it but through those who are seen as outsiders and in need of cooption. Students must give up their cynicism and help improve the system or their despair may drive them to self-destruction like the youngsters in Rang de Basanti. And criminals must never learn that they are a necessary appendage to big business but instead ought to give up their violent ways, learn some manners, and use their native wisdom to help people who are struggling to cope in a world where old family values seem to be eroding rather rapidly.

Ordinarily, identification with criminals is a complex negotiation involving revulsion as well as attraction. By domesticating the hoodlums and divesting them of their menace, Lage Raho Munnabhai simplifies this process. Similarly, the young audience can easily identify with the youngsters in Range De Basanti who speak and behave like them, not only because of the naturalistic portrayal, but also because their own social position makes it possible for them to momentarily understand the cynicism of someone like DJ, who says that with one foot in the past and the other in the future he is pissing on the present. However, the difficulties of the present, as experienced by these characters with whom the audience identify, are simply the difficulties of a section of people who actually stand to gain from the economic transformation taking place in our society, provided they participate sensibly. Hence, Gandhi’s Satyagraha can be relieved of the burden of its history as one of the most potent weapons against British imperialism and become “Gandhigiri,” a gentle tool to sort out civic tensions. And because the truly exploited majority is always already forgotten, Bhagat Singh who had forewarned against “brown evil replacing the white” need not be summoned for anything more than holding our hand as we merrily take off on this bumpy ride.

Aarti Wani is a lecturer in English at Symbiosis College of Arts, Commerce, & Computer Science, Pune. A member of AIDWA (All India Democratic Women’s Association), Wani is involved in many youth-, media-, and culture-related activities and projects in the city. This article was first published by Film International.

|

| Print