|

Annual Fundraising Appeal

Friends of MRZine and Monthly Review! The continuing existence of MRZine and Monthly Review depends on the support of our readers. Unlike many other publications, we make all new Monthly Review articles, as well as MRZine articles, available online, free of charge. We do so without drawing any advertising money at all from Google ads, pop-up ads, and other scourges of the Net. How then can we continue our work? We need your financial support! To donate by credit card on the phone, call toll-free: You can also donate by clicking on the PayPal logo below: If you would rather donate via check, please make it out to the Monthly Review Foundation and mail it to:

Donations are tax deductible. Thank you! |

“I’d like to say that people . . . people can change anything they want to. And that means everything in the world. Show me any country . . . and there’ll be people in it just trying to take their humanity back into the center of the ring . . . . And follow that for a time. Y’know, think on that. Without people you’re nothing.” — Joe Strummer

Is anything left in music that is even vaguely redeeming? In the face of all the soulless pabulum being fed to us in the MTV-strangled airwaves, I often wonder if the industry has won. When rock n’ roll is so full of the cynical, the snide, the intentionally ironic, it seems like record companies are signing bands that not only won’t say anything but won’t feel anything. Not caring is the fad of the day, and righteousness is passé, naïve, and stupid.

Antonino D’Ambrosio agrees. As we sit in a bar on the Lower East Side of New York City, we talk about the sense of collective amnesia from which many bands suffer. As the head of La Lutta New Media Collective, D’Ambrosio is aware that most of today’s artists have little bark and even less bite. He is also the editor of Let Fury Have the Hour: The Punk Rock Politics of Joe Strummer, a book devoted to the Clash front man, now in its fifth printing in two years. Almost four years after Strummer’s death in December of 2002, it is amazing how few remember the seismic effect the Clash had on music. “Every band out there is a Clash imitator,” the author tells me, “but half of them don’t know who the Clash were.”

Indeed, when the National Review claims “Rock the Casbah” as a top “conservative rock song,” something really went wrong. “When the right wing starts moving in on rock n’ roll, it’s scary,” he says. As a son of Italian immigrants growing up in Philadelphia, D’Ambrosio knows what it looks like when the right wing has its grip over a whole city. In the early eighties, around the same time the Philly police were throwing the members of MOVE into jail, he was being introduced to the sounds of the Clash’s music, an experience he recalls in his book: “When I heard, really heard the Clash’s music for the first time, it came by way of the song ‘Clampdown.’ I related to it as it seemed written for me. It became more than a song: ‘Clampdown’ was my own personal anthem. The Clash promised rebellion. And I was certain that they could deliver it and liberate me from a sense of hopelessness and a life of ‘wearing blue and brown.'”

D’Ambrosio isn’t alone. A common thing to hear from Clash fans is “that band changed my life.” And it is easy to see why. “Some might say the Clash was the greatest punk band of all time,” he thinks aloud. “If you’d ask me who the greatest punk band of all time was, I’d say Bad Brains. But the Clash was without a doubt the greatest Rebel Rock band of all time.” What the Clash was rebelling against was clear, too. In 1970s London, where newspaper headlines screamed of unemployment, race riots, and police brutality, rebellion was the only sane thing to do. When Strummer got together with Mick Jones, Paul Simonon, and Terry Chimes (later replaced by Topper Headon), they knew which side they wanted to stand on. And it is no exaggeration that their musical rebellion changed rock n’ roll forever.

Since Strummer’s untimely death, a whole crop of books have sprung up paying homage to the Clash, each claiming to be the definitive story of the band. Some are better than others. But none highlights the importance of Strummer’s own politics in his life and work like Let Fury Have the Hour. In a little under 350 pages, D’Ambrosio compiles pieces from iconic music journalists like Lester Bangs and political musicians as diverse as Billy Bragg and Chuck D. He also includes his own words on Strummer, whom he met and talked to, not too long before his death. Each piece is unique, but all of them make it very clear who Strummer was: an artist who looked at the world around him and did what he could to change it for the better. “Joe always said his politics was Marxist,” Antonino tells me, “but I always thought it was humanist before anything else.” Marxist or not, it is undeniable that Strummer had a deep sense of compassion and solidarity with his fellow human beings that was reflected in his life and music.

Today there are both detractors and so-called “fans” of Strummer who say that political stances can only do disservice to music and that musicians have no role in social change. Whether they like it or not, however, people listen to what artists have to say. Back at the bar, Antonino relates a story to me, obscure but poignant. In the late seventies, when far-right groups were on the rise along with unemployment in the UK, fellow punkers the Jam (known for dressing in mod-style suits) announced they were voting Conservative in the elections. While the Jam’s conservative turn would dog the band throughout their career, few know Strummer wrote one of the Clash’s greatest songs, “(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais,” as a response to it:

The new groups are not concerned

With what there is to be learned

They got Burton suits, ha you think it’s funny

Turning rebellion into moneyAll over people changing their votes

Along with their overcoats

If Adolf Hitler flew in today

They’d send a limousine anyway

This isn’t only one of punk’s quintessential anthems, it’s a piece of political dialogue, and a brilliant one at that! To the “art for art’s sake” crowd, a sin against music itself. But to the kids in 1970s London looking for a way out, it was a crucial warning and a call to arms.

It was moves like this that made the Clash more than mere entertainers — active participants in the world at large. The band headlined the Rock Against Racism shows in 1978, openly supported political prisoners in Northern Ireland, and spoke out against the crushing of the British miners’ strike in the mid-80s. Naturally, any major record exec cringes at the very thought! In the mind of a suit (if there is a mind in a stuffed suit), artists shouldn’t think — they should sing, dance, and rake in the dough. A clearer proof of that can’t be found than the band’s constant fight with CBS Records that D’Ambrosio chronicled in Fury. The company initially refused to release the Clash’s first album in the States (though it would later become the biggest-selling import in US history). When the band insisted on selling double and triple albums for single album prices, the label would force them to cover the difference out of their own pockets. And when they named their fourth record Sandinista! the execs panicked. “The label heads said our music would not sell — too political,” says Joe, “especially in America where the Reagan administration was conspiring to destroy the Sandinistas.”

Despite this, the band, and Joe, never backed down. After the Clash’s demise halfway through the hellish eighties, Joe reemerged a few years later as a solo artist and sometime actor, appearing in films like Alex Cox’s Straight to Hell and Jim Jarmusch’s Mystery Train. These films reflected Joe’s rebel outlook, as did his music. The three albums he released with the Mescaleros, the band he played with until his death, were quintessential Joe Strummer. They are musically eclectic, danceably catchy, and thoroughly human. Now signed to independent label Hellcat, Joe embraced a wide variety of musical styles, from rock to worldbeat, from rocksteady to folk. Songs like “Bhindi Bhagee” promoted ethnic tolerance, “Johnny Appleseed” was a send-up of corporate globalization, and his cover of Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song” would prove as relevant sung by Joe as it was by Marley twenty years before.

It was during this last era in Joe’s work that D’Ambrosio had the chance to meet him. And the picture he conveys in his book gives the reader a good sense of how Joe evolved in his later years. He was older and wiser, yes. But he never sold out, never compromised, and never stopped believing that the world is worth fighting for. It’s this idea that prompted the author to compile Fury after Joe’s death.

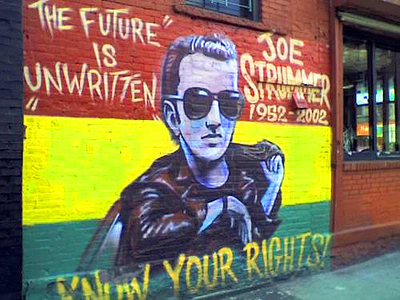

I talk to Antonino about the video for “Redemption Song” (the only one off Streetcore, released after his death), a sublime piece of NYC filmmaking that documents the painting of a mural dedicated to Joe not long after his death. As it turns out, the mural is close to the bar where we are drinking. While we walked to the mural through the cold winter night, I looked around New York and thought of Joe’s own connection with the city. “He’s a god here on the Lower East side,” I’m told. No surprise.

At 7th and A, the vibrant mural is visible from down the street. It is painted in the Rastafarian colors of red, yellow, and green. At the center of the mural is a spray-painted image of Joe, his leather jacket slung over his shoulder. “THE FUTURE IS UNWRITTEN” is scrawled next to Joe’s head, and “KNOW YOUR RIGHTS,” at the bottom of the mural. The higher-ups in the music industry have taken advantage of Joe’s death. We can now hear the Clash’s songs being used to sell cars and cell phones. It’s the sound of their legacy made safe for mindless consumption. The mural, however, reminds us of what Joe really stood for.

When Joe died of heart failure at the age of fifty, he was working on a song dedicated to the life of Nelson Mandela. The mainstream music press offered perfunctory “tributes” to Joe, glossing over his passion for social justice. But, for fans whose lives were touched by his music, the sense of loss was greater than any article could express. With the US already rattling sabers to go into Iraq, the void Joe left was deeply felt by many. Four years later, it still is.

Outside the boardrooms of Sony and EMI, there are those of us who look to music to remind us that we’re not alone, to help us make sense of a frightening world, and to inspire us to believe that we can change anything if we want to. Joe’s music changed our lives, and we have not forgotten the truly incendiary power that music can have.

What is the best way to remember Joe Strummer? To build the kind of world he fought for. And who are the builders of a new world? “You know,” Antonino says to me as the night winds down, “if anyone were to ask Joe ‘who is the next Clash?’ he’d say ‘you are.'”

Let’s prove Joe right.

Alexander Billet is a music journalist living in Washington DC. He is currently working on a book of his own entitled The Kids are Shouting Loud: The Music and Politics of the Clash. He also maintains the blog Rebel Frequencies:rebelfrequencies.blogspot.com. He can be reached at [email protected]. For a copy of Let Fury Have the Hour, go to the website for Nation Books.

|

| Print