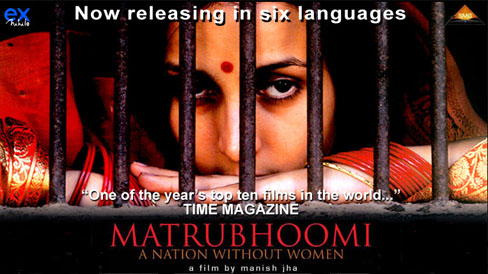

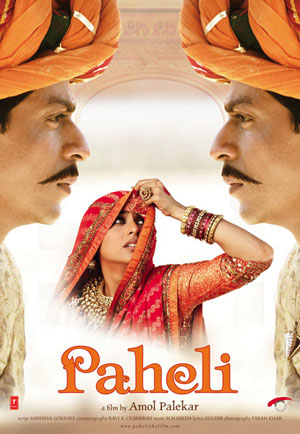

Two films, Paheli and Matrubhumi: A Nation without Women, hit theatres in India within weeks of each other. Significantly, both the films, directed by Amol Palekar and Manish Jha respectively, have or claim to have women at the centre of their discourse. In the promos of Paheli, the producer-actor Shah Rukh Khan talked of the film as an attempt to portray the needs and desires of a woman, to explore, in short, what women really want! Matrubhumi, on the other hand, as the title suggest, looks at the possibility of a nation without women. Paheli is — surprisingly for its director Palekar, who has in the past been highly critical of mainstream cinema — a commercial film complete with stars, song and dance, and a show of opulence. Matrubhumi, eschewing all the necessary trappings of a masala Hindi film, takes a hard look at a possible future. Given that both the films speak of women, it would be interesting to compare them in terms of the positions they take and the ideological underpinnings that are thereby revealed within the larger context of the changing realities of women’s existence in our society.

In India, more than anywhere else, the question of women’s emancipation, equality, and freedom is enmeshed in complexities and contradictions. Trapped between feudal, caste ideologies and structures on the one hand and the pressures of consumerist competitiveness ushered in by globalization on the other, women find themselves, their bodies and identities, becoming a site of contestation. If a large section of women are even today victims of age-old patriarchal attitudes and systems that deny them education, independence and the right to self-determination, there are also women struggling, individually as well as collectively, to assert their right to work, dignity, and justice. In evidence are also a desire and efforts to redefine their relationships with men and other women, their role within the family as also their commitment to the larger issues in the world around them. But in the last decade globalization has impacted women’s lives in a variety of ways. At the one end of the spectrum are the significant beneficiaries of neo-liberal policies: the very affluent, highly educated, and upwardly mobile. To this bracket belong professional women in high-paying jobs as well as housewives with extremely consumerist lifestyles. Some of these women are able to exercise a degree of freedom in their personal lives in terms of the choice of sexual partner(s) and/or orientation Although the global media has played a part in promoting personal freedom, it has also been responsible for the fetishising of women’s bodies through advertisement, music videos, soaps, and other programmes that has led to a commodification of not only women but also what they are valorized for: love and sex! At the other end of the spectrum are poor women in rural as well as urban areas, literally struggling to make ends meet. Neoliberal policies have taken away jobs as they slowly destroys the public distribution system, making mere existence a daily effort. Similarly affected are women farmers who are being driven to the very edge of sucide. Finally, patriarchal values, son preference, and greed for a lifestyle promised by globalization, technology, and the global media’s projection of women as sex objects all coalesce together to essentially increase violence against women across the spectrum. The skewed sex ratio — an effect of sex-selection abortion, dowry deaths, and general violence against women — reflects the total alienation of human sensibility that has taken place today. It is against such a reality that any film claiming to make a statement about women has to be judged.

When we look at these two films, Paheli (A Riddle) and Matrubhumi (Motherland), we are struck by an interesting similarity. Both the films imagine a time and place other than the exact present. Paheli goes back in time to an unspecified past, where, one gathers, life is much more feudal and patriarchal than now. Based on Vijay Dan Detha‘s short story “Duvidha,” it tries to recreate a world gone by, a world where ghosts were common, where people traveled in bullock carts and entertainment was provided by puppet theatre. In contrast, Matrubhumi imagines a future, a dystopia, a nation without women. Obviously, both the films are really attempts to say allegorically something of relevance to the lives of women today. And, it is here that the similarity ends.

Paheli’s plot, except for its end, remains by and large true to that of “Duvidha.” It tells a story of a young girl and a ghost. The girl is married to a trader who leaves home for business on the day after the wedding, without the marriage being consummated. But a ghost who has seen the girl on her way to her husband’s home has fallen in love with her and, on realizing that the husband has left for five years, takes his form and comes to her. Since the ghost is truly in love with the girl, he reveals his true identity to her on the first night. The girl, after agonizing about it for a while, accepts him, and they start living together. After four years, the husband, on hearing rumours of his wife’s pregnancy, returns home. The two, the ghost and the man, both claiming to be the girl’s husband, are given a test to determine their authenticity. During the test, the ghost is tricked into a bag and left to his fate on the desert floor, and the real husband assumes his rightful position in the household and his bedroom. The girl is heartbroken but not for long. It soon becomes evident that the ghost has slipped out of the bag and into the husband’s body to the great delight of the girl, and the film ends on this happy note. The overall happiness of the mood is reinforced by opulent sets, shiny and colourful clothes and jewelry, and glamourous stars

Paheli’s plot, except for its end, remains by and large true to that of “Duvidha.” It tells a story of a young girl and a ghost. The girl is married to a trader who leaves home for business on the day after the wedding, without the marriage being consummated. But a ghost who has seen the girl on her way to her husband’s home has fallen in love with her and, on realizing that the husband has left for five years, takes his form and comes to her. Since the ghost is truly in love with the girl, he reveals his true identity to her on the first night. The girl, after agonizing about it for a while, accepts him, and they start living together. After four years, the husband, on hearing rumours of his wife’s pregnancy, returns home. The two, the ghost and the man, both claiming to be the girl’s husband, are given a test to determine their authenticity. During the test, the ghost is tricked into a bag and left to his fate on the desert floor, and the real husband assumes his rightful position in the household and his bedroom. The girl is heartbroken but not for long. It soon becomes evident that the ghost has slipped out of the bag and into the husband’s body to the great delight of the girl, and the film ends on this happy note. The overall happiness of the mood is reinforced by opulent sets, shiny and colourful clothes and jewelry, and glamourous stars

.

Paheli is evidently an attempt, though a light-hearted one, at making a statement about women’s needs, desires, and agency. In the original story, the possibilities of the written word allow the writer to trace the thoughts of the girl who finds herself in such a strange situation. In the film, on the other hand, when the ghost declares himself and confesses his love, the girl sheds a few tears of confusion and then immediately accepts him as her lover. From here on the film has no use for her. The focus is on the ghost, and intermittently on the husband, who is shown to be missing the wife he had been so prompt in leaving.  The ghost is full of love for the girl and she basks in it as she reciprocates. But till the end she faces no difficulty due to her choice, confronts no conflict in terms of social opposition or pressure. The question doesn’t arise because her lover is a ghost who looks exactly like her husband. In our society, most women are unable to exercise their will, not so much from inner inhibition as from fear of public outcry and persecution. The girl in the film (as well as the original story) has it easy because of the surreal plot device that makes any potential problem disappear.

The ghost is full of love for the girl and she basks in it as she reciprocates. But till the end she faces no difficulty due to her choice, confronts no conflict in terms of social opposition or pressure. The question doesn’t arise because her lover is a ghost who looks exactly like her husband. In our society, most women are unable to exercise their will, not so much from inner inhibition as from fear of public outcry and persecution. The girl in the film (as well as the original story) has it easy because of the surreal plot device that makes any potential problem disappear.

The ghost in the film is supposed to be symbolic, standing for the ideal love/lover every woman desires, according to the promotional interviews of the film. At one point in the film (as well as the original story), in answer to the husband’s query about his identity, the ghost replies that he is the “love” in a woman’s heart. As mentioned earlier, Paheli‘s end is different than that of “Duvidha.” And it is a difference that is crucially important. In Detha’s story, the ghost is tricked into a bag, and the bag is thrown in the river. The ghost is thus truly defeated. The last paragraph of the story describes the girl walking towards the bedroom with the baby at her breast grieving over her fate. Even animals, she rues, are freer than women, and all that a woman can hope for is better life for her daughter! Detha’s story has folksy simplicity, but its ending pointedly confronts real problems faced by real women. In a feudal, patriarchal family and social structure, a woman is able to exercise very little control and choice. When the ghost comes to her, she easily overcomes any inhibition she may feel and accepts him with open arms. But it is beyond her powers to choose him over her rightfully wedded husband. The defeat of the ghost in the story is in that sense meaningful because it is in keeping with his earlier assertion that he is a reflection or an embodiment of the love in a woman’s heart, in other words, what a woman really desires. But between a woman’s dream and its fulfillment is a whole social system that has for centuries discriminated against women. Dreams, even those of loving husbands and sexual fulfillment, can become realities only if the whole structure changes. A woman cannot go on living in a completely patriarchal world and get her heart’s desires. That can happen only in a mainstream Hindi film like Paheli that is looking not only for a sweet palatable end but also for an easy, fairy-tale solution to an extremely complex social problem.

Matrubhumi, although it creates an imaginary future world, is in fact a result of looking hard and long at the present-day reality. The opening describes a scene of birth, with the mother in labor and the father waiting anxiously. But “unfortunately” a girl is born and promptly killed. At the end of the film the director quotes the census figures: 35 million girls have disappeared in India due to gender discrimination. If this continues, the film warns in no uncertain terms, we shall be a nation without women. This brave new world is represented by a village somewhere in north India where not a single woman can be found. The film is grim but not without its moments of dark humour. For example, a man dresses up as a woman and performs for other men, singing and dancing to raunchy bollywood numbers. Taking advantage of the paucity of women, a father tries to pass off his young boy for a girl and earn a good sum from a youth who would buy a bride. An old man has tears in his eyes at a show of a pornographic film. Pornography, masturbation, homosexuality, and bestiality — practices condemned by many who encourage son preference — are ironically the only options left in the world without women that they helped to create.  Then, a family of five brothers and a father move centre stage. The sons, desperate for marriage, nag their father to find a girl. But there are no girls to be found in all the surrounding villages until the priest spots Kalki, kept hidden and protected behind high walls by her father. The father, who is unwilling to marry her to the eldest of the five sons because he looks rough and would rather give her to his younger gentle-looking brother, ends up marrying her to all five for a much larger sum. Kalki’s existence in her new home — where the brothers take turns with her at night and also the father demands his share in her sexual exploitation — is a wretched hell. It is to the credit of the director that he handles this potentially voyeuristic situation with subdued suggestiveness rather than with explicit crude violence.

Then, a family of five brothers and a father move centre stage. The sons, desperate for marriage, nag their father to find a girl. But there are no girls to be found in all the surrounding villages until the priest spots Kalki, kept hidden and protected behind high walls by her father. The father, who is unwilling to marry her to the eldest of the five sons because he looks rough and would rather give her to his younger gentle-looking brother, ends up marrying her to all five for a much larger sum. Kalki’s existence in her new home — where the brothers take turns with her at night and also the father demands his share in her sexual exploitation — is a wretched hell. It is to the credit of the director that he handles this potentially voyeuristic situation with subdued suggestiveness rather than with explicit crude violence.

Kalki’s only solace is the youngest brother, whose sensitive understanding of her situation brings them close. Kalki has a friend also in a young lower-caste servant boy who almost instinctively connects with her.  The moments between these three speak of human resilience in the most savage of times and provide the only relief in a film that stares relentlessly at a world gone inhumanly cold. But the brothers cannot tolerate Kalki’s affection and special relationship with their youngest brother, and he must pay for his gentleness with his life. In a world where there are no women, men are reduced to even greater brutality. Women in such a world are ever more mere receptacles for men’s lust and no ordinary poetry of a male-female relation will thrive, the director seems to say.

The moments between these three speak of human resilience in the most savage of times and provide the only relief in a film that stares relentlessly at a world gone inhumanly cold. But the brothers cannot tolerate Kalki’s affection and special relationship with their youngest brother, and he must pay for his gentleness with his life. In a world where there are no women, men are reduced to even greater brutality. Women in such a world are ever more mere receptacles for men’s lust and no ordinary poetry of a male-female relation will thrive, the director seems to say.

Kalki’s attempt to escape this hell with the servant boy’s help result in his murder and a caste war, in which, once again, Kalki becomes the prize that “higher”- and “lower”- caste men fight over. Although Kalki had found a comrade in this adolescent, for the rest of the lower-caste men, she is not only just a woman but also a sign of upper-class privilege and arrogance. Violence, mayhem, and death follow. The film ends on a strange note. Almost all the men have been killed as Kalki gives birth, with the help of another young lower-caste boy, to a girl. Stark and unsparing, the film takes a hard look at a possible future. If the present trend of sex-selection abortion, dowry deaths, and general violence against women continues, the film argues, men will live a lonely, desparate, and beastly existence, and finally end up killing each other. Perhaps only then can women make a new beginning, with the help of others who have been equally week and oppressed

Matrubhumi is a horrific nightmare. And like a nightmare it is extreme, grotesque, and irrational. For example, apart from Kalki we do not see a single woman in the village, not even middle-aged or old mothers of the adolescent boys we see around. Similarly, it is not possible that men miss women only sexually; after all, an immense amount of work is done by women, both at home and in the fields. But such logic is out of place in the bleak vision of the film. And its particular vision is the result of unflinchingly facing the brutalization and commodification of human relations in general and its specific effect on women in a society caught between traditional son preference and “modern” consumerist greed. Kalki’s father starts flaunting a car and a mobile phone once he has made a profitable deal of selling her for five lakhs, one for each brother. He is indignant in reaction to Kalki’s complaint that even her father-in-law demands his right over her body, but only because he feels cheated — he simply comes to collect one more lakh. Clearly, this is a reversal of the present scenario, where the growing demands for dowry are after all triggered by the lure of consumer durables. For the few who have benefited from it, globalization has brought in its wake a lifestyle of buying and spending. For many it is merely a dream that beckons. The dowry system that was in the past confined to specific communities is now becoming universal because dowry is seen as a means to make the elusive dream come true. If women keep on burning for dowry or, alternatively, are denied life because of the parental fear of the often impossible burden of dowry, then the day is not far, the film warns, when they would themselves become rare “commodities” for which men will pay with their lives.

Paheli‘s dream chooses to ignore the realities of women’s life, past or present, that is assumed and implied in Matrubhumi. Its end, the ghost inhabiting the husband’s body seems to suggest a change of heart in men as a solution to the problem of the thwarting of women’s desire. Modern India, as mentioned earlier, has given a handful of urban, affluent, and educated women a degree of freedom and independence to exercise their will in at least some walks of their lives. Even here, however, it is not simply a matter of a change of heart, either of men or women. The objective conditions of their lives have changed! Paheli‘s quick-fix solution is therefore problematic not only because it is unreal but because it presumes to advocate women’s freedom of choice and agency in matters sexual without questioning the hierarchical structure of family that is entrenched in larger class and caste structures of oppression and exploitation. Mainstream Hindi films are by and large extremely “audience friendly” and hence avoid disquieting truths. But given the director’s pretensions to meaningful cinema, our habitual indulgence cannot be granted to the film. Paheli‘s choice of a more palatable end than the original “Duvidha” reveals an ideological position that assumes that liberation, even sexual liberation, is merely a matter of individual choice and agency. In contrast, Matrubhumi is in touch with the real and understands not only the oppressiveness of economic and social structures but also the human endeavor to overcome them. Paheli is

a sugar-candy dream — it tastes sweet but is empty of substance. Matrubhumi is, on the contrary, a nightmare which wakes you up in cold sweat.

Aarti Wani

is a lecturer in English at Symbiosis College of Arts, Commerce, & Computer Science, Pune. A member of AIDWA (All India Democratic Women’s Association), Wani is involved in many youth-, media-, and culture-related activities and projects in the city.