For as long as Wall Street has stood for greed and unearned profits there have been those who have stood against it.

In 1890, the leader of the Knights of Labor railed at “the control of our financial affairs by the bulls and bears of Wall Street.” Six years later, a spokesman for New York workingmen denounced politicians and financiers as “fire-eaters, demagogues, libelers, corruptionists, fanatics and Wall Street gamblers.”

But the first occupation of Wall Street proper occurred during the early months of 1914, when Emma Goldman and Upton Sinclair, as well as hundreds of their socialist and anarchist comrades, descended on lower Manhattan to protest the callousness and cruelty of the plutocratic elite.

Conditions in 1914 were as bad as they have ever been. An industrial depression had left more than a quarter of a million city residents out of work. Charity services were overwhelmed. At night, during the early winter months, the parks were crowded with sleeping homeless people. Meanwhile, radical street speakers stirred the destitute masses, nurturing unrest. “At Rutgers Square, at Tompkins Square Park, in Mulberry Bend, almost anywhere in the tenement districts,” one anarchist organizer recalled, “a few minutes of speech-making would draw a thousand people together.”

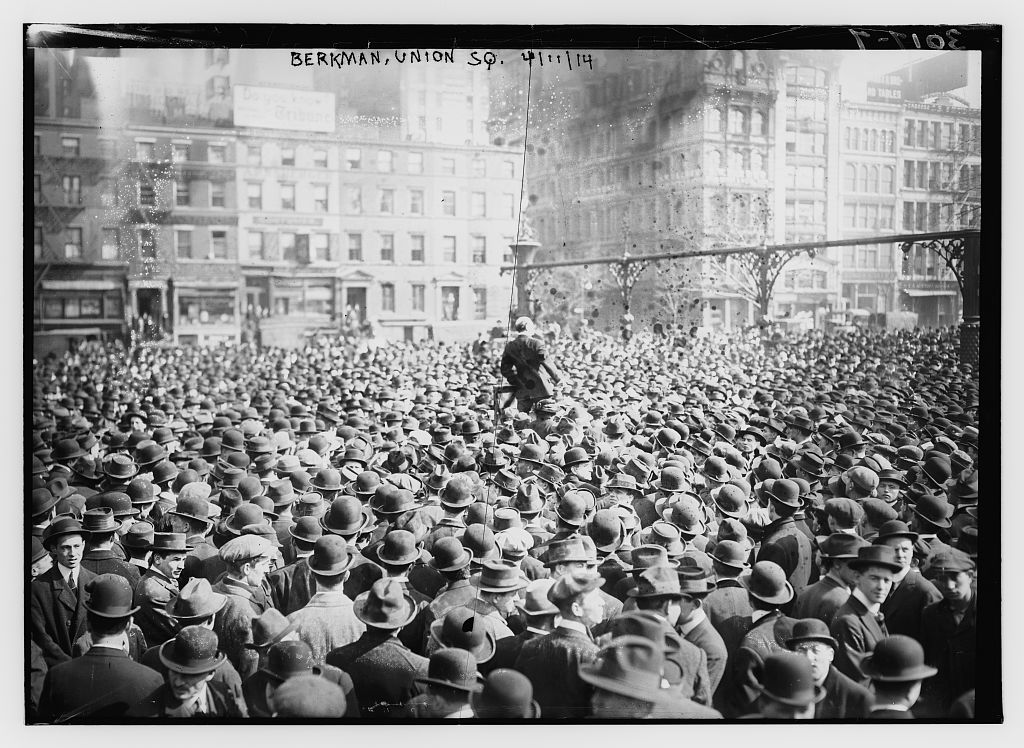

On Saturday afternoons throughout the spring, thousands of angry demonstrators gathered in Union Square to speak out against social iniquities. “Your toil made the wealth of the nation,” Emma Goldman shouted to the crowds in late March. “The rich are keeping it from you. March upon Fifth Avenue and take that which belongs to you!”

When hundreds of anarchists followed her lead, terrorizing the city’s most affluent neighborhood, alarmed city fathers determined to suppress this sudden militancy. In April, club-wielding policemen charged a peaceful rally in Union Square. Mounted officers trampled the protesters while several leaders of the movement were beaten and arrested.

|

Then as now, official violence only boosted sympathy for the victims and encouraged others to join the movement. Liberal opinion swung toward the radicals as the press denounced the brutality of the officers’ methods. The mayor attempted to curb the police department’s excesses. Within days, the police commissioner was fired and his replacement entered office determined to protect the protesters’ rights of free speech. Allowing dissidents to voice their opinions, he argued, was the best way to ensure that their activities would not escalate toward even more violent tactics.

The following Saturday, when anarchists again gathered at Union Square, the police kept out of sight. Speakers went unmolested as they decried the capitalist classes. Despite the heat of the rhetoric the rally ended peacefully. “There was no show of force at all, and no abridgment of free speech,” wrote Lincoln Steffens, the muckraking journalist. “It was an experiment in liberty, and liberty worked.”

Tolerance on the part of the police stole the passion from the protesters. Subsequent demonstrations drew only a few dozen people. Organizers were bewildered by the sudden change, but “Big Bill” Haywood, the leader of the radical Industrial Workers of the World, understood what had happened. “With the clubbing came the converts,” he explained, “and after there was no more martyrdom there were no more additions to the ranks.”

If events had ended here, they would have offered a comforting example of the efficacy of progressive policing and tolerant governance. But within weeks the newfound peace in the city was disrupted by external events. In late April, word reached the city that a long-simmering labor conflict in the Rocky Mountains had turned violent. Mine guards and militiamen, controlled by the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, had invaded a union encampment, killing a score of people, including two women and eleven children. The attack would become known as the Ludlow Massacre, and in New York it inspired hundreds of protesters to descend on Lower Manhattan.

|

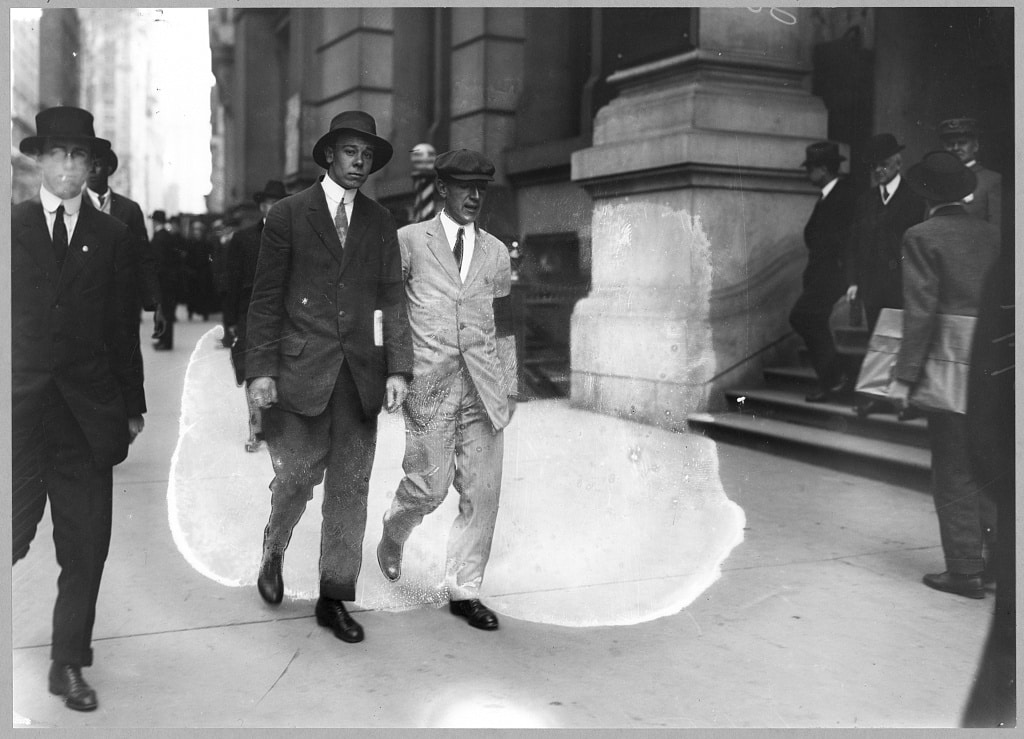

Led by Upton Sinclair, the 35-year-old author of The Jungle, radicals determined to force the Rockefellers to accept accountability for the killings. For weeks, dozens and sometimes hundreds of protesters picketed the sidewalks in front of the Standard Oil Building at 26 Broadway — just a few blocks from today’s Zuccoti Park — in what was perhaps the first occupation of Wall Street.

Committed to nonviolence, they wore crepe armbands to signify a funeral for the Colorado dead. Fanning out from Lower Manhattan, anarchists soon established demonstrations in front of the Rockefellers’ mansions on West 54th Street; they even rode trolleys up to Westchester County to mount picket lines at the gates to the family’s country estate near Tarrytown.

The Rockefellers no longer appeared in public. Armed detectives patrolled their property. Newspapers around the world reveled in the spectacle of their disgrace. “Thirty-six dollars and seventy-five cents have one billion two hundred million eighty-nine thousand dollars surrounded,” a Chicago magazine sneered, “John D. Rockefeller, the richest man in the world, and his son, John D., Jr., are today as close prisoners in their estate as are the convicts in Ossining penitentiary.”

|

Then, as summer began, the months-long protest fervor climaxed disastrously. Around 9 a.m., on Independence Day, a tenement building at 1626 Lexington Avenue — between 102nd and 103rd streets — erupted in a cascade of smoke and debris. The bodies of three anarchists were discovered in the rubble; a bomb they had been constructing had accidentally detonated prematurely — their probable target had been John D. Rockefeller.

The broad coalition that had rallied to the movement quickly disaggregated. The police commissioner’s tolerant stance no longer appeared so enlightened. Suddenly, the administration found itself accused of recklessly coddling revolutionaries. Reversing course, the city began infiltrating and sabotaging the activities of radical groups. More conflict between anarchists and police would follow, culminating eventually in the deportation of Emma Goldman and the 1920 Wall Street bombing that killed 38 people.

The protests of 1914, which unfolded through a series of tactical decisions concerning the use of violence, potentially suggest a variety of useful lessons to today’s protesters and administration. In the end, though, tactics are secondary to the central issues at stake — the grievances of the demonstrators concern a social system that extends far beyond the jurisdiction of the mayor and police. However the current occupation of Wall Street ends, it will have as much to do with forces beyond the city as with the tactical responses of local officials.

Thai Jones is a PhD candidate in U.S. History at Columbia University. His new book — More Powerful Than Dynamite: Radicals, Plutocrats, Progressives, and New York’s Year of Anarchy — will be published by Walker Books in April 2012.

| Print