Bastille Day 2005 inaugurates the new Monthly Review Webzine. Paris is also an excellent place to begin a series on social medicine. For it was in Paris, in 1830, that one of the seminal papers in social medicine appeared. While the Parisian workers overthrew Charles X, the last of the Bourbons, a French physician, Louis Rene Villerme published a paper examining mortality patterns in different Parisian arrondissements (districts).

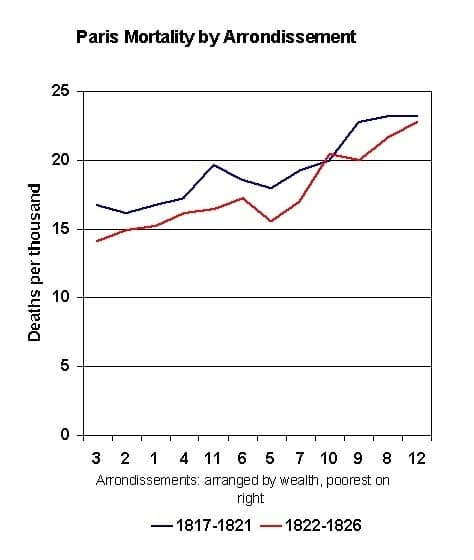

Villerme began with the simple observation that mortality rates differed greatly from one arrondissement to another. (See table 1) The lowest death rate was 14.1/thousand in Arrondissement 3; the highest was 22.7/thousand in Arrondissement 12. Further, when Villerme compared the five year periods 1817-1821 and 1822-1826, these patterns remained stable. The differences between the arrondissements were not the result of chance.

Villerme carefully sought the explanation for these differences using the conceptual tools of his time. He tried to correlate mortality with the distance of the arrondissement from the Seine River, the relationship of the streets in the arrondissement to the prevailing winds, the arrondissement’s source of water and local climatological factors such as soil type, exposure to the sun, elevation and inclination of the arrondissement.

Villerme carefully sought the explanation for these differences using the conceptual tools of his time. He tried to correlate mortality with the distance of the arrondissement from the Seine River, the relationship of the streets in the arrondissement to the prevailing winds, the arrondissement’s source of water and local climatological factors such as soil type, exposure to the sun, elevation and inclination of the arrondissement.

Finally, in a result Villerme called “quite remarkable,” he found that mortality patterns correlated nearly perfectly with the degree of poverty in the arrondissement. As a measure of poverty, he used the percentage of people in the arrondissement exempted (because of low income) from a particular tax. Thus, the arrondissements arranged in terms of poverty correlated quite well with the observed differences in death rates. In the table, the richest arrondissements are on the left; the poorest on the right. Villerme provided solid statistical confirmation of a key principle in understanding health: health and wealth are closely associated. Social class is a key, perhaps the key determinant of health.

This result remains as true today as in 1830. Recently the World Health Organization established a Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. The head of the Commission, Dr. Michael Marmot, offered a pithy 21st century version of Villerme’s findings:

Let’s take the United States, for example. If you catch the metro train in downtown Washington, D.C., to suburbs in Maryland, life expectancy is 57 years at beginning of the journey. At the end of the journey, it is 77 years. This means that there is [a] 20-year life expectancy [gap] in the nation’s capitol, between the poor and predominantly African American people who live downtown, and the richer and predominantly non-African American people who live in the suburbs.

The creation of the WHO Commission is evidence that the study of what is called “the social determinants of health” is undergoing something of a renaissance right now. Ironically, the political climate seems more and more hostile to public health. In fact, it is probably symptomatic of this political climate that more money goes to the academics to study the problem. I am told that there are some 1200 papers examining the relationship between poverty and ill health. Do we really need more research?

Much of the academic work — and that of the WHO Commission — seeks “factors” to explain the relationship between poverty and ill health. Does this relationship correlate with income, education, political participation, women’s access to health care, or some other factor? By discovering factors, can we come up with targeted interventions — money for Head Start programs, nutrition programs for young children, “empowerment” programs — that will alleviate these social inequalities? Such programs are usually touted for their “low cost” and proven efficacy in economic terms. After all, we wouldn’t want to feed children just because they were hungry or educate them just because it would make their lives richer.

Villerme was one of a generation of socially-minded physicians who looked at — and denounced — the impact of the Industrial Revolution in European cities. Friedrich Engels, in his book on the conditions of the English working class, drew on the work of these physicians to demonstrate the inhumanity of capitalism and the need for social revolution.

I suspect that Mr. Engels would shake his head at this search for “factors.” The heart of a capitalist economy, its economic soul, rests on the exploitation of one class by another. How then can we hope for health equality among the classes? The “factors” simply reflect in a variety of ways the core of capitalism. Certainly, whatever factor one might look at — education, income, housing, nutrition, political liberty — the Parisians of 1830 are quite a different group from the Washingtonians of 2005. And yet the core relationship between health and wealth holds true.

In summary, the best way to stay healthy is to chose the right parents, the ones who live in the right neighborhoods.

Conferences: July 17 to July 22 will see the second People’s Health Assembly in Cuenca, Ecuador. The Assembly will bring together health activists from around the world broadly united by the goal of reanimating the Alma Ata Declaration. News and updates can be found at the Assembly Website <http://phmovement.org/pha2/> .

Sources: A page-by-page PDF file of Villerme’s article is available from the Bibliotheque Nationale de France at <http://gallica.bnf.fr/Catalogue/NoticesInd/FRBNF37303496.htm>. The complete text of Engels’ The Condition of the Working Class in England is available on the web at <http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/condition-working-class/>.