I’m writing a preface for a new edition of my memoir, Red Dirt: Growing Up Okie, which first appeared in 1997 — it’s about my life growing up poor, rural, super-patriotic, and Christian fundamentalist in Oklahoma, and still becoming anti-imperialist, Marxist, anti-racist, and feminist. I am trying to deal with the red-state (the South and Midwest) / blue-state (the two coasts) dichotomy that reared its head during the 2004 presidential election as a part of the post-911 traumatic stress syndrome. Of course, nothing is that simple — some states have razor-thin majorities of one or the other, while other states have significant regions or cities colored opposite to the state as a whole. Yet, one thing is certain: Oklahoma, electorally, fits comfortably into the red state category, and has for some time, long before the signifiers were coined.

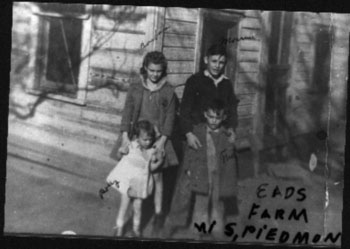

But, that was not always the case. “Red” in the title of Red Dirt predated the label “red” for Republicans, though it can be added to the litany of reasons I chose it. I was thinking, first, of the red soil in rural Canadian County where I grew up and where my father tried to scratch out a living as a tenant farmer. Secondly, Oklahoma originally was territory that the federal government established as a homeland for the Indians that it forcibly removed from the Southeast during the 1830s. My mother was in part descended from those “red” people. Third, my paternal grandfather was a Socialist and a Wobbly, active in the Socialist Party and in the Industrial Workers of the World. He and other Reds were victims of the Wilson administration’s “red scare.” Not only my grandfather, but also at least twenty percent of Oklahomans during that time were “reds,” and many more were sympathetic. The Socialist Party won local elections all over the state, and a significant percentage of voters supported their own presidential candidate in five elections. Their activity and general pro-unionism in Oklahoma created the most progressive state constitution in the country.

But, that was not always the case. “Red” in the title of Red Dirt predated the label “red” for Republicans, though it can be added to the litany of reasons I chose it. I was thinking, first, of the red soil in rural Canadian County where I grew up and where my father tried to scratch out a living as a tenant farmer. Secondly, Oklahoma originally was territory that the federal government established as a homeland for the Indians that it forcibly removed from the Southeast during the 1830s. My mother was in part descended from those “red” people. Third, my paternal grandfather was a Socialist and a Wobbly, active in the Socialist Party and in the Industrial Workers of the World. He and other Reds were victims of the Wilson administration’s “red scare.” Not only my grandfather, but also at least twenty percent of Oklahomans during that time were “reds,” and many more were sympathetic. The Socialist Party won local elections all over the state, and a significant percentage of voters supported their own presidential candidate in five elections. Their activity and general pro-unionism in Oklahoma created the most progressive state constitution in the country.

By the time I was coming of age in the 1950s, Oklahoma had been for three decades a tightly run proto-fascist state, with oil and wheat keeping a small ruling class super-wealthy and the rest of the population poor and ignorant. That ruling class controlled every institution, including the media. Those of us who disagreed were expected to leave, and those of us who were able did so, leaving a hard core of Baptist and corporate control and a fearful population. Oklahoma’s transition from traditional Dixiecrat Democrat to right-wing Republican, like the South as a whole, happened with the Republican Party’s “southern strategy” of the Nixon era.

How I came to disagree can be attributed to two family secrets that were whispered in oblique stories. One was about my mother’s mother being part Indian. The other was about my father’s father being a Red — a radical socialist and member of the IWW. The secret about being part Indian was kept, because it was both dangerous and shameful to be an Indian in Oklahoma before the 1960s. My father warned me to keep secret stories about his Wobbly father that he told me, because it was dangerous and shameful to be a Red at the time, the communist witch hunting time of “McCarthyism.” Somehow, those secrets became the core of my imagination and identity.

This experience has informed me in assessing the present red-blue configuration, with Protestant fundamentalism, laissez-faire capitalism, and super patriotism linked with war being the ruling political ideology. Having grown up Southern Baptist and super-patriotic, I know what it is like to view the world that way, and how powerless I felt to effect change, but I also know how alternate information can be transforming.

(Some may wonder what would have become of me had I not moved to California and experienced the “Sixties.” But, people do not have to leave oppression to be free; they can — and often do — resist it where they are.)

It’s amazing to me how many otherwise intelligent leftists and liberals of the two coasts believe there is a growing surge of voting masses in the South and Midwest that are reflections of Ann Coulter and Ralph Reed. Yet, some sixty percent of eligible voters — citizens — do not vote in national elections. And in polls, the majority of people say they do not want Roe v. Wade overturned, say the Iraq war is wrong, favor domestic partners, etc. Only twenty percent of the U.S. population claims to be fundamentalist Christians, surely a whopping figure when mobilized, but why blame the other eighty percent of us for the power of the right wing agenda that the Christian right offers? The results of the 2004 election brought out class hatred of the white working class that must be embedded in the minds and emotions of many liberal/left activists and gatekeepers. Thomas Frank’s What’s the Matter with Kansas? was embraced as an oracle for telling us about the dumb working-class white people who vote against their economic interests (Kerry’s capitalism vs. Bush’s capitalism?). Surely, some did vote for Bush, especially the aroused fundamentalist ones, but most of them — like most young people, women, Blacks, Latinos — did not vote at all. They just don’t see voting as an effective means of resistance. Maybe they aren’t so dumb after all.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz is a long-time activist, university professor, and writer. In addition to numerous scholarly books and articles, she has written three historical memoirs, Red Dirt: Growing Up Okie (Verso, 1997), Outlaw Woman: Memoir of the War Years, 1960–1975 (City Lights, 2002), and Blood on the Border: A Memoir of the Contra War (forthcoming October 2005 from South End Press) about the 1980s contra war against the Sandinistas.