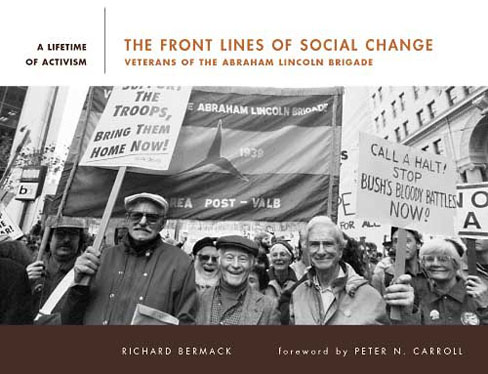

The Front Lines of Social Change: Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. By Richard Bermack, Introduction by Peter Carroll. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2005. 120pp, oversize. $19.95pbk.

This is a photo book with text, and Richard Bermack is the master photographer of veteran political activists on the West Coast. He has been on the job for over thirty years, placing his own 1960s ego in the background (no easy generational task), taking oldtimers for what they are at literal face value. You could say that the photos themselves looked more deeply.

The Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (properly speaking, a “Batallion,” but hardly anyone remembers the fine point of sematics) have been Bermack’s favorite subject over the years, and with good reason. They sum up, in their extraordinary courage (many of their relatives would have said foolhardiness) and self-sacrifice, the internationalism of the 1930s radical generation. Most of them might rather have fought the capitalist class almost anywhere than struggling to hold onto “bourgeois democracy” against a threatening fascist offensive in Europe, but they did not choose their own turf. It chose them.

Once committed, they did not look back. That the Soviet leaders and the Comintern should have been more democratic and more revolutionary, less authoritarian and downright hypocritical, most of the survivors (not all) would not freely admit. But their own behavior, with few exceptions, was exemplary. And it’s true, as we historians look back at the 1930s, that, if Franco had been defeated, if the fascist advance had been halted, then the Second World War would, at a minimum, have taken a different course in its first years. Arguably, the Holocaust could have been prevented. And in the last years of war, the Truman administration’s alliance with fascist collaborators from France to Spain to Greece and far beyond would have been harder to pull off. We might have had a different world.

Bermack employs photo archives of the “Abes” (as they are often called by the inner circle) as youths, along with his own photos of them in later years, to show what they were and what they became. The brave faces look out at us twice over, each one heroic. Some precious old literary documents, from the poems of Mike Quin to the poetry of Edwin Rolfe, decorate the pages.

|

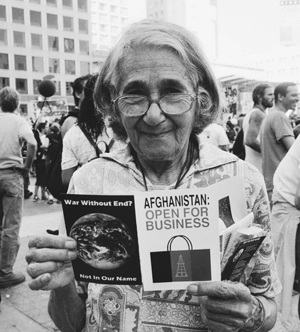

From one standpoint, it is a superb oral history, because Bermack is so attentive to the memories. If oral history is inevitably (despite many hopes of oral historians after “facts”) about states of mind in the present, Bermack records the subsequent shocks, from repression at home to the Khruschev Revelations, as part of the life story. What comes out in the end — and it’s a very long ending, because the ALB veterans were active throughout the 1960s, closing out their political lives only when they died or became too infirm to join a picket line — is no political orthodoxy, but pure courage.

Whoever has met these folks in later years (years that extend through my own political lifetime) will likely shed a silent tear while leafing through these pages. With them, a generation passes. But thanks to Richard Bermack, they did not pass unseen or unheard.

Paul Buhle, currently a lecturer in history and American civilization at Brown University, is author or editor of twenty-seven books on radicalism, labor, and popular culture, including five volumes on the films of the Hollywood blacklistees. Most recently, he coedited Wobblies: A Graphic History (2005) and The New Left Revisited (2003), winner of an American Library Association’s Choice Academic Book Award. He has written for The Nation, Times Higher Education Supplement, The Guardian, and the Journal of American History, among others. He founded the journal Radical America (1967-95), the Oral History of the American Left project (New York University), and the Community and Labor Oral History project of Rhode Island.