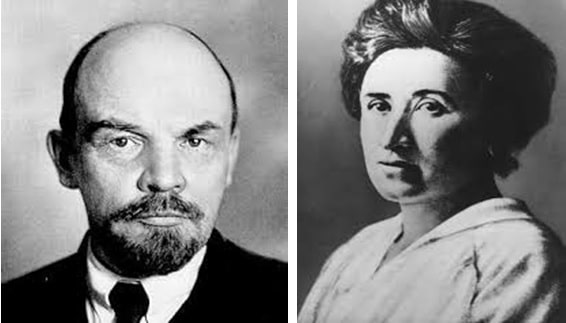

Lenin: Responding to Catastrophe, Forging Revolution. By Paul Le Blanc. London: Pluto Press, 2023, 245pp. $18

Rosa Luxemburg: The Incendiary Spark. By Michael Löwy, edited by Paul Le Blanc. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2024. 168pp. $18

The Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, based in Berlin, recently issued a bulletin entitled, “Seven Reasons Not to Leave Lenin to Our Enemies.” This was intriguing because Rosa was one of Lenin’s sternest critics, and during the Cold War era, her works found print in the United States as vindication of current U.S. policies against the Soviet Union. The disciples—or were they merely the confused followers?—of Lenin’s principles seemed to the anticommunists the greatest threat to democracy, and Luxemburg was obviously the cure.

This was always a misrepresentation of Rosa the revolutionary. For decades, within the Left, Rosa’s reputation had been defended most ardently by the disciples of Trotsky, thus also inevitably of Lenin as well. During the 1960s, the sudden appearance of the New Left and Feminism raised her status so greatly that she, or rather her reputation, seemed beyond Lenin. Perhaps that was only a momentary, in any case. The similarity of their views on empire, on the expansion of empire as capitalism’s last resort and on the struggle against empire as a phase in socialist history at larger, continues the spiritual partnership-of-sorts.

The two books under review offer, together, a useful popularization well suited to the interests and the hopes of the coming leftwing generations now so active on the campuses and communities. They also return us to old questions in new ways, with sometimes surprising insights.

Michael Löwy is a near-legendary figure in modern Marxist thought. Raised in Brazil, he joined a miniscule Trotskyist group before shifting to Paris in 1961. Rosa Luxemburg was already very much on his mind, despite the criticism rained upon her over the decades by reformist socialists, Bolsheviks, hardline Communists, and academic cold warriors. Löwy has always been a bit of a Luxemburgite, for a long time within the Fourth International. Meanwhile, he taught and wrote unique books in different parts of Europe. Interested in Hegelianism, Surrealism, Anarchism, and other matters far from the usual Marxist map, he has been slow to come to the attention of American readers. Perhaps now, as Löwy has reached his middle eighties, his proper place will be found. And in a good place, with Rosa. Here, at any rate, we have a collection of essays published over the decades, going back to the 1960s and up to the present, looking at Luxemburg from different angles.

She has been “speaking” to my own new left generation for a long time. By the middle 1960s, some of us found pamphlets of her writings, in English, published in Ceylon! As Löwy notes, the first substantial English language collection of her writings, offered by Monthly Review Press in 1971, was a “Radical America Book,” the first of a projected series bearing the stamp of a magazine that I founded in 1967. This particular “Luxemburgian” project ended suddenly, with the collapse of the New Left. Four decades later, I was happy to have organized the creation of Red Rosa (2015), the graphic novel drawn by Kate Evans, which has had almost a dozen editions in various languages, making it a vehicle reaching young, global generations.

What Luxemburg called for and Löwy reiterates is, in brief, a “conception of socialism that is both revolutionary and democratic—in irreconcilable opposition to capitalism and imperialism—based on the self-emancipatory praxis of the workers, on self-education through experience and on the action of he great popular masses” (p.23). Nothing less. “Red Rosa” thus bitterly opposed the bland reformism of the German Social Democrats who accepted Empire (Germany’s own, that is) and the imperial state as part of progress, if only it could be guided a bit better. As she, a great admirer of Lenin’s accomplishments, nevertheless also opposed the drift of Leninism away from constant collaboration with the masses.

Contrary to the semi-anarchist readings of Luxemburg devotees over the decades, she very much believed in the training of a revolutionary party, even if its commands apparently needed, as Lenin himself suggested, to be superseded at certain moments of crisis. If she was critical of existing Bolshevism, she was in favor, if one may put it this way, of a better Bolshevism, toward which Lenin in his last years seems to have been himself pointing.

Alongside Luxemburg’s writing and organizing in practical terms (even reformers in the Social Democratic Party regarded her as the finest teacher in the party schools), we find her decisive insights into the consequences of colonialism. Here we come usefully to Paul Le Blanc, whose latest work on Lenin covers much familiar ground, in a particularly lively manner.

For some readers, including myself, the Lenin of the Global South—among his final writings, he insisted that the struggles there made the overthrow of capitalism inevitable—and the last-moment struggles against Stalinism seem the most pressing today. If global capitalism, including the capitalism of the United States, is in a sea of trouble, yet trouble always seems to be pushed away, deferred, by the power of capital—until a Day of Reckoning that has not yet come. For those outside the zones of good fortune, existence itself is in doubt. That today they suffer the most from the effects of global warming is only the worst of a centuries’ old list of woes.

I would suggest that Le Blanc is in line with another recent volume of the lighter touch, Lenin: the Legacy We Do (Not) Renounce, by a hundred writers. Many of them offer amusing and revealing anecdotes about the Lenin legacy, like the contributor who gives intermittent “baths” to the little bust of Lenin inherited from his father, murdered for owning Lenin texts more than a half century ago. Like the Abraham Lincoln book end on my bookshelf, those Lenin items—statuettes, lapel pins, not to mention posters and murals—have never ceased to be present around the world and show no sign of disappearing.

We truly are living in a “Lenin world,” notwithstanding the collapse of the East Bloc. Nobody is clearer than Le Blanc, who has a firm grasp of the “Catastrophe” of the title. He lays out, in practical terms, Lenin’s sense of Party and strategy, his admiration for artistic expression, and above all his insistence upon the creative independent action of the proletariat.

That all this Lenin stands so far from popular stereotypes brings us back sharply to Luxemburg. In a chapter entitled “Western Imperialism against Primitive Communism,” Löwy explains that Luxemburg’s precise understanding of ongoing imperialist invasions led her to develop a text, from prison, with more space devoted to “primitive communist society and its dissolution” (p.54) than to the capitalist market economy. The Introduction to Political Economy (1914-15, edited and published by Paul Levi in 1925) was clearly intended to destroy misguided beliefs in the supposed “eternal nature” of private property. Drawing upon semi-anthropological sources then available, she insisted upon the universality of the agrarian commune.

From this standpoint, the European invasion of Africa or the British Invasion of India was not at all the “uplifting” claimed by the imperialists, but rather the opposite. The old connections broken by force, militarized imperialism and its economic counterpart brought misery and little else.

One can take exception to Löwy’s insistence that Rosa and Leon, Luxemburg and Trotsky, stand intimately together—and hail his effort to place Luxemburg and Lukacs in relation to each other, very much notwithstanding Lukacs’ philosophical criticisms of her in History and Class Consciousness. We can appreciate these giants better when we put them in a version of a dialogue, long after their passing, and no one does that better than Löwy… and Le Blanc.

Find these books and put them in the hands of young people.

Paul Buhle has been a Monthly Review contributor since 1970