Everything has changed! Nothing has changed!

Barring unexpected difficulties, a new coalition has been formed in Berlin. Gerhard Schroeder, confident, even arrogant until his final days as leader, has been replaced by the first woman in German history to head a government, and she’s an East German at that, though she has never yet pushed for the rights of women or East Germans.

And for the first time since 1969, the country will be ruled by a coalition of the two main parties, the right-of-center Christian Democrats (CDU), plus their Bavarian sister party the Christian Social Union (CSU), and the Social Democrats (SPD), still occasionally called left-of-center. Each will have eight Cabinet posts; the two sides are now fine-tuning a joint policy.

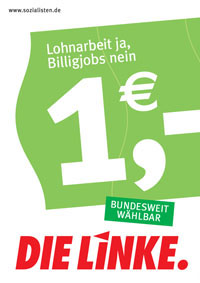

No, the change is not a big one. The CDU, although in opposition since Schroeder’s SPD beat their Kohl government in 1998, has been a more than loyal opposition. Oh, they cursed away at the inefficiency, the blunders, the false policies of the SPD, often in angry, excited tones. But when the chips were down, they supported nearly every key policy of the government. And well they might, for these policies, almost without exception, were just what the doctors ordered — the doctors, professors and other experts closely tied to big business. Their prescription for getting out of the long-lasting economic mess — with unemployment circling near 10 percent (over five million people) and hitting twenty percent or more in eastern areas — was to cut taxes on the wealthy, drop taxes on corporations, charge for medical services which had always been free, raise prices steeply on medicine and medical aids, push for partial privatization of future pensions and freeze the present ones despite inflation, take weak “optional” measures to help young people desperate for job training, cut the long-term unemployed to a starvation level, forcing them to take jobs paying one or two Euros an hour or lose all benefits, look the other way at attempts by industry to demand more work hours per week, less vacation, less protection against layoffs — in short, policies to destroy a decent standard of living that years of struggle (assisted by the existence of two competing German states) had helped most workers achieve. The CDU reaction was “Right on! But even sharper cuts!”

The anti-social policies, agreed on by both government and opposition in the past, proved to be a failure. Now the two have united, threatening an alarming future.

True, unlike the CDU, Schroeder opposed the Iraq war, enabling him to squeak through the election of 2002: East German voters, who made the difference, overwhelmingly opposed the war. But he took active part in the Balkan Wars and in Afghanistan. Peter Struck, his defense minister, made official policy very clear: In the past fifteen years, “the entire world has become the field of operations for the Bundeswehr [the German armed forces].”

What about the three smaller parties in the Bundestag?

The Free Democrats, once a middle-class libertarian party, moved further and further to the right over the years and are as closely tied to big business as the CDU. They expected to be a junior partner of the CDU and were busy choosing ministerial jobs for their leaders. But alas, their 61 seats plus the 226 of the CDU did not achieve a majority (of 614). They have now been left out and are still sulking in the corner.

The Greens were once a vigorous left-wing party. But the years as junior partners of the SPD got them three ministerial posts, including that of Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer, and tamed most of their former radical urges. They backed Schroeder’s anti-social program all the way and, despite their old pacifist roots, even the policy of military expansion and war. The early election, which they opposed, pushed them out of any power — with 51 seats, they are now the weakest party in the Bundestag and have few positions of strength anywhere.

But the political situation has seen one potentially crucial change. There is a new factor in the Bundestag, the Left, composed of the former Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), totally reformed grandchild of the old ruling GDR party (SED), with most of its strength in eastern Germany, and the Electoral Alternative for Jobs and Social Justice (WASG) a new formation, stronger in West Germany, with some angry union leaders, anti-globalization groups, and disappointed Social Democrats. Only the PDS was in the old Bundestag, with two young women — Gesine Lötzsch and Petra Pau — elected directly by East Berlin constituencies; in the elections of 2002, the party missed the 5 percent required for full Bundestag participation.

But the political situation has seen one potentially crucial change. There is a new factor in the Bundestag, the Left, composed of the former Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), totally reformed grandchild of the old ruling GDR party (SED), with most of its strength in eastern Germany, and the Electoral Alternative for Jobs and Social Justice (WASG) a new formation, stronger in West Germany, with some angry union leaders, anti-globalization groups, and disappointed Social Democrats. Only the PDS was in the old Bundestag, with two young women — Gesine Lötzsch and Petra Pau — elected directly by East Berlin constituencies; in the elections of 2002, the party missed the 5 percent required for full Bundestag participation.

|

|

Lötzsch and Pau were almost completely ignored, indeed insulted, and many in the corridors of power obviously hoped that the PDS would simply disappear after a new defeat.

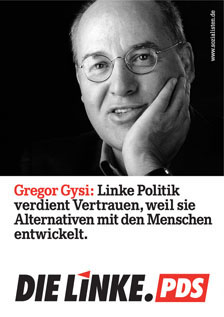

But the unexpectedly early election campaign inspired former PDS leader Gregor Gysi and Oskar Lafontaine, a new WASG leader (once head of the SPD before he quit in disgust), to join hands in an alliance.

|

|

A new party has not yet been formed (despite some problems this should occur within a year or so). But when the PDS agreed to change its name, the WASG agreed to run on its ticket. The combination of the two, with unexpected new strength in western areas, enabled the party to win 8.7 percent of the vote; that meant 54 deputies in the Bundestag, more “Wessis” (from the West) than “Ossis” (from the East), 26 men, 24 women — and the opportunity to become a real opposition.

The Left’s mere presence has already had results. Schroeder’s SPD, fearing a really left-wing program after it swerved right for seven years, suddenly started pushing a less anti-social program — it modified its own prescribed hardships and claimed to be the party of the “little people, union members, the jobless, the single mothers, the poor.” Enough fell for this — or feared the alarming greater evil threatened by Angela Merkel and her spooky accomplices — to help the SPD catch up in the vote, missing victory by about one percent, and this same fear of a genuine left is now forcing it to make social demands in negotiations on a new government plan. Perhaps some of the worst horrors can be prevented — or delayed — for this new, aggressive opposition will hinder attempts to push through anti-social domestic legislations and expansionist foreign policies which have had virtually no one to expose them in the Bundestag. 54 delegates of the Left can no longer be ignored, by Bundestag leaders or by the media. Of course, they will certainly try to split the Left delegation when possible. Since it is a very varied group, most of whose members have little experience in such a body, this is a constant danger. But the very presence of left-wing delegates in every committee and every debate, even though they can hardly pass laws by themselves, will make life difficult for those who have hitherto listened only to the lobbyists — or their tax and investment advisers. Perhaps it will even be possible to link the actions of the Left in the Bundestag to those in the factories, schools, hospitals, and on the streets. What a change that could make!

Yes, there will be plenty of wrangling among members of the new government coalition. But the scene at the top has not really changed radically. At the base where it counts, however, there may be some profound changes.

Victor Grossman, American journalist and author, is a resident of East Berlin for many years. He is the author of Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany (University of Massachusetts Press, 2003).