[Click on the photos to see original images.]

Part I. The World Festival of Youth and Students, August 8-15, 2005

Caracas, Venezuela, Seen from a Park Above

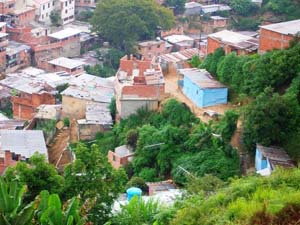

Poor neighborhood — “barrio” — in Los Teques, the capital of the state of Miranda, near Caracas, where we spent our nights during the 16th World Festival of Youth and Students. My group — including delegates from Libya, Japan, and the United States, plus a Jordanian and a Puerto Rican — stayed in an abandoned Gilette factory, which now serves as a government building since being taken over by the state.

Poor neighborhood — “barrio” — in Los Teques, the capital of the state of Miranda, near Caracas, where we spent our nights during the 16th World Festival of Youth and Students. My group — including delegates from Libya, Japan, and the United States, plus a Jordanian and a Puerto Rican — stayed in an abandoned Gilette factory, which now serves as a government building since being taken over by the state.

Opening ceremony of the World Festival of Youth and Students in Caracas, Venezuela, attended by about 16,000 delegates from 144 countries, according to official sources. The theme of the festival was “For peace and solidarity, we struggle against war and imperialism.” The Festival has a Communist history, having been organized in the past almost exclusively by Communist Parties (with a capital C). Communist Parties had a large presence at this festival in Caracas as well, but they were by no means alone. Delegations from the Americas were very diverse, including youth groups, student groups, Trotskyists, liberals, anarchists, Maoists, and other leftists and progressives of many sorts.

Opening ceremony of the World Festival of Youth and Students in Caracas, Venezuela, attended by about 16,000 delegates from 144 countries, according to official sources. The theme of the festival was “For peace and solidarity, we struggle against war and imperialism.” The Festival has a Communist history, having been organized in the past almost exclusively by Communist Parties (with a capital C). Communist Parties had a large presence at this festival in Caracas as well, but they were by no means alone. Delegations from the Americas were very diverse, including youth groups, student groups, Trotskyists, liberals, anarchists, Maoists, and other leftists and progressives of many sorts.

Heroes of revolutions. Above, a message from the Venezuela Communist Party depicts Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Simón Bolívar. Below, Venezuelan independence fighters Francisco de Miranda and Simón Bolívar join Che Guevara on a message from the Frente Francisco de Miranda, a kind of revolutionary social work organization.

In the “Poliedro” (“Polyhedron”) stadium, during an “anti-imperialist tribunal,” at which President Hugo Chávez Frías and others made cases against imperialist powers for their crimes. Chávez has the eloquence and longwindedness typical of Latin American leaders. But he has a little bit more of both than most. His imprecision and tendency to move freely from one topic to another sometimes disappoints some leftists. There is much to debate in his anti-imperialist discourse, which often leaves class inequality as a secondary issue, and which leads him into alliances with other governments of questionable political legitimacy. But Chávez knows how to inspire an audience, and I found his eclectic blends of theory and historical allusions very engaging. How many national presidents will you hear cite Leon Trotsky and Rosa Luxemburg in their speeches, as Chávez did on two occasions during the Festival?

In the “Poliedro” (“Polyhedron”) stadium, during an “anti-imperialist tribunal,” at which President Hugo Chávez Frías and others made cases against imperialist powers for their crimes. Chávez has the eloquence and longwindedness typical of Latin American leaders. But he has a little bit more of both than most. His imprecision and tendency to move freely from one topic to another sometimes disappoints some leftists. There is much to debate in his anti-imperialist discourse, which often leaves class inequality as a secondary issue, and which leads him into alliances with other governments of questionable political legitimacy. But Chávez knows how to inspire an audience, and I found his eclectic blends of theory and historical allusions very engaging. How many national presidents will you hear cite Leon Trotsky and Rosa Luxemburg in their speeches, as Chávez did on two occasions during the Festival?

Part II. “Social Tour” of Caracas Neighborhoods, August 11, 2005

A traditional dance, performed by children from the San Juan area of Caracas. The neighborhoods we visited on this “social tour” prepared cultural performances for the visiting delegates from the World Festival of Youth and Students, in addition to showing us the forms of community organization that have recently sprung up in the neighborhoods. There are “land committees” that oversee land use, “health committees” that coordinate the work of Cuban doctors who live in the neighborhoods, “women’s committees” that deal with issues of concern to women; there are also several “missions” centered in schools that provide literacy classes and adult education. According to one woman, it was after the coup in April, 2002 that people began to really organize themselves, rather than relying on the government. “Chávez gave us the tools to organize ourselves,” she said. But the organization would have to come from below.

Office of a Cuban doctor — this construction style is typical for medical centers built by the Bolivarian government. Behind the office is an abandoned shoe factory. There is some discussion of re-starting the factory as a cooperative.

Part III. “Social Tour” of Los Teques Neighborhoods, August 12, 2005

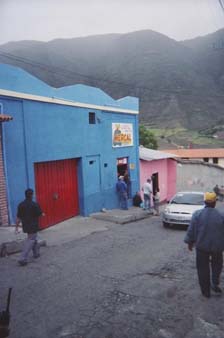

The building of a community radio station near Los Teques, state of Miranda. Its antenna rises up over the right side of the house.  The operator of the radio station, which broadcasts for 12 hours every day but Friday, said that people realized the necessity of community-based media during the coup of April 2002, when the corporate media blocked all information that might undermine the coup’s success. During the coup, people put loudspeakers on a truck and drove it through the neighborhoods, broadcasting information that would “not be televised.” Pavel, our guide and revolutionary militant, named after a character in Gorky’s novel Mother, is in army fatigues on the left. He is an instructor in the Army Reserve, which he sees as a kind of popular army, more democratic than the regular army.

The operator of the radio station, which broadcasts for 12 hours every day but Friday, said that people realized the necessity of community-based media during the coup of April 2002, when the corporate media blocked all information that might undermine the coup’s success. During the coup, people put loudspeakers on a truck and drove it through the neighborhoods, broadcasting information that would “not be televised.” Pavel, our guide and revolutionary militant, named after a character in Gorky’s novel Mother, is in army fatigues on the left. He is an instructor in the Army Reserve, which he sees as a kind of popular army, more democratic than the regular army.

A new local government takes office just after local elections were held, in which about 80% of those elected were from parties supporting the Bolivarian revolution, in one way or another. Unlike after previous elections, the opposition seemed generally to accept these elections as fair. They had some minor complaints, but primarily they faulted their own disunity for their poor showing. A wide variety of political currents now run in elections under the Bolivarian banner of Chávez. Chávez’s party, the Fifth Republic Movement, is by far the largest. It is joined by a number of groups with uninformative names like “Homeland for All,” “We Can,” and the “Union of Electoral Victors.” Many people I met suspect these parties of opportunism, leaping on the Bolivarian platform only for personal gain. Other Bolivarian parties come from more clearly leftist roots: the Venezuelan Communist Party, the Trotskyist Revolutionary Marxist Current, and the guerrilla-inclined Tupamaros all have been growing, while other smaller groups have recently been formed. I did not find significant left groups outside of the Bolivarian movement (those that support the opposition have mostly lost their radical orientation), but there exists a good deal of mutual criticism and debate among those who support the “revolutionary process.”

Unlike after previous elections, the opposition seemed generally to accept these elections as fair. They had some minor complaints, but primarily they faulted their own disunity for their poor showing. A wide variety of political currents now run in elections under the Bolivarian banner of Chávez. Chávez’s party, the Fifth Republic Movement, is by far the largest. It is joined by a number of groups with uninformative names like “Homeland for All,” “We Can,” and the “Union of Electoral Victors.” Many people I met suspect these parties of opportunism, leaping on the Bolivarian platform only for personal gain. Other Bolivarian parties come from more clearly leftist roots: the Venezuelan Communist Party, the Trotskyist Revolutionary Marxist Current, and the guerrilla-inclined Tupamaros all have been growing, while other smaller groups have recently been formed. I did not find significant left groups outside of the Bolivarian movement (those that support the opposition have mostly lost their radical orientation), but there exists a good deal of mutual criticism and debate among those who support the “revolutionary process.”

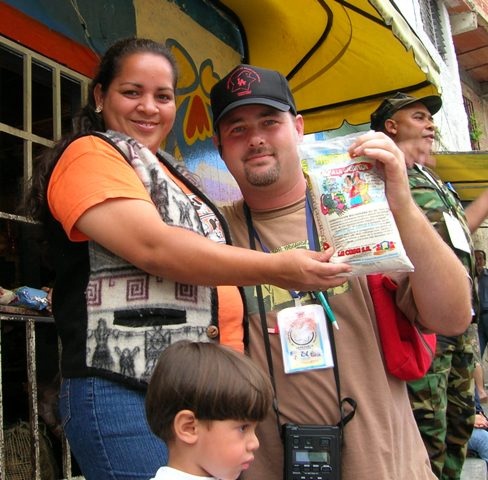

In front of mercal, a store selling subsidized foodstuffs. Such stores have been opened in a large number of communities around the country.

Part IV. Travels through Venezuela, August 15-23, 2005

|

|

Mural, in the Andean city of Mérida. I traveled west to Mérida with 3 other people I had met in the World Festival of Youth and Students.

Mural, detail. Shortly after taking this photo, we met a man who told us he was one of the artists of the mural. He invited us to give an interview on his community radio show that evening, but we were set to leave for higher and smaller places.

The office of a Cuban doctor in a barrio of Mérida, on the steep slopes by the river that runs through town.

A wool cooperative in the village La Mucuchache, above Mucuchíes, about 3,200 meters above sea level. The technique used in this picture, we were told, is used mostly to impress tourists. Usually, the cooperativistas use sewing machines. They are, however, trying to develop sewing machines that will be easier to fix, including some that require no electricity, in order to improve their self-sufficiency. This cooperative aims to expand its activities to involve all aspects of wool production from the raising of sheep to the sale of woven products. Again, the goal is self-sufficiency. All of the members of this cooperative are women, most of whom had no direct source of income previous to this project.

A wool cooperative in the village La Mucuchache, above Mucuchíes, about 3,200 meters above sea level. The technique used in this picture, we were told, is used mostly to impress tourists. Usually, the cooperativistas use sewing machines. They are, however, trying to develop sewing machines that will be easier to fix, including some that require no electricity, in order to improve their self-sufficiency. This cooperative aims to expand its activities to involve all aspects of wool production from the raising of sheep to the sale of woven products. Again, the goal is self-sufficiency. All of the members of this cooperative are women, most of whom had no direct source of income previous to this project.

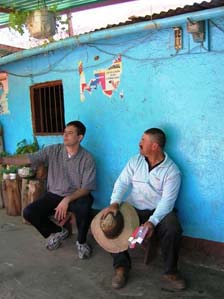

A farmer in Apartaderos (another village above Mucuchíes, around 3,200 meters above sea level), member of an association of campesinos and a participant in several social programs, including some aimed at re-introducing local varieties of potatoes, which had been pushed out of the market by agribusiness after World War II. Over lunch, the farmer and the volunteer who was our guide explained how they had begun to support the Bolivarian government, after initial skepticism: during the course of their attempts to re-introduce local agricultural products, twice their efforts were sabotaged by the minister of agriculture and his friends in agribusiness. Eventually, they were able to take their case all the way to President Chávez, who fired the minister of agriculture. I heard many other similar stories, usually with the moral that the people would have to organize themselves to demand that the government bureaucracy do what it was supposed to do. People constantly criticized corrupt politicians and functionaries, while usually emphasizing their support for Chávez himself.

A farmer in Apartaderos (another village above Mucuchíes, around 3,200 meters above sea level), member of an association of campesinos and a participant in several social programs, including some aimed at re-introducing local varieties of potatoes, which had been pushed out of the market by agribusiness after World War II. Over lunch, the farmer and the volunteer who was our guide explained how they had begun to support the Bolivarian government, after initial skepticism: during the course of their attempts to re-introduce local agricultural products, twice their efforts were sabotaged by the minister of agriculture and his friends in agribusiness. Eventually, they were able to take their case all the way to President Chávez, who fired the minister of agriculture. I heard many other similar stories, usually with the moral that the people would have to organize themselves to demand that the government bureaucracy do what it was supposed to do. People constantly criticized corrupt politicians and functionaries, while usually emphasizing their support for Chávez himself.

“Chávez Birdge,” in Gavidia, up a different mountain valley above Mucuchíes, at 3,500 meters above sea level. This is high in the “páramo” region, and very cold. It was 4 degrees Celsius the afternoon we were there.

“Chávez Birdge,” in Gavidia, up a different mountain valley above Mucuchíes, at 3,500 meters above sea level. This is high in the “páramo” region, and very cold. It was 4 degrees Celsius the afternoon we were there.

After a meeting of the cooperative, I asked its members what they thought of the Venezuelan government and what they saw as the goal of their work in the cooperative. Most people supported Chávez and the government, though one cooperativista preferred to remain “apolitical,” and another said that Chávez is wonderful, everything would be wonderful if he could be everywhere, except that those around Chávez are much less honorable and capable than he is. The goals of the cooperative, I learned, were to improve their lives and those of their community. When I asked how they related to the ideas of “socialism” and “capitalism,” they suggested that these abstractions were not very meaningful to them.

The next day we left Mucuchíes, heading for Barinas, en the Llano–plains–region of Venezuela. The road through the mountains was long and winding. On the hilltops in the distance are four white domes of the second highest astronomical observatory in the world.

Barinas, the small city in which President Chávez spent most of his adolescence. This is his high school. That afternoon, we met the president’s brother, who works in the government building of the state of Barinas. We also visited the INCE institute, a government body which promotes the formation and management of cooperatives. The promotion of cooperatives is now one of the government’s top priorities, and several different agencies work together on it. As some of the employees of INCE explained to me, they hope to create an “alternative to capitalism,” not by expropriating private property and sending capitalists away, but by creating a superior, parallel economy, which will gradually replace the one that dominates right now. But many different theories and strategies compete within the Bolivarian movement.

Barinas, the small city in which President Chávez spent most of his adolescence. This is his high school. That afternoon, we met the president’s brother, who works in the government building of the state of Barinas. We also visited the INCE institute, a government body which promotes the formation and management of cooperatives. The promotion of cooperatives is now one of the government’s top priorities, and several different agencies work together on it. As some of the employees of INCE explained to me, they hope to create an “alternative to capitalism,” not by expropriating private property and sending capitalists away, but by creating a superior, parallel economy, which will gradually replace the one that dominates right now. But many different theories and strategies compete within the Bolivarian movement.

Mural on the “House of Youth” in Barinas, where, by chance, we met some young activists who showed us around the city.

Mural on the “House of Youth” in Barinas, where, by chance, we met some young activists who showed us around the city.

A street in Valencia. We stayed with friends for three days near Valencia, the capital of Carabobo state and the primary industrial city of Venezuela. Our friend’s father is the president of the Federation of Unions of University Employees, a longtime communist. As with many leftists in Venezuela, the Bolivarian revolution took him by surprise. “We don’t know where Chávez came from,” he said to me once, “but he came, and everything changed. We are learning from him.”

Our friend’s father is the president of the Federation of Unions of University Employees, a longtime communist. As with many leftists in Venezuela, the Bolivarian revolution took him by surprise. “We don’t know where Chávez came from,” he said to me once, “but he came, and everything changed. We are learning from him.”

INVEPAL, the first successfully worker-occupied enterprise in Bolivarian Venezuela. After a struggle that lasted more than a year, the government assented to workers’ demands to “nationalize under workers’ control.” It is a paper factory.

INVEPAL, the first successfully worker-occupied enterprise in Bolivarian Venezuela. After a struggle that lasted more than a year, the government assented to workers’ demands to “nationalize under workers’ control.” It is a paper factory.

One of the elected representatives of the INVEPAL factory gave us a tour. The internal affairs of the factory are decided almost entirely by the workers, in a combination of meetings and through elected representatives. The enterprise’s management council also includes representatives of the state, which owns 51% of the factory, to the workers’ cooperative’s 49%. On the shop floor, there are no bosses. Debates continue as to the proper role of the state and the union in the management of the factory. In part of the factory there is a museum dedicated to the workers’ long struggle to take it over.

which owns 51% of the factory, to the workers’ cooperative’s 49%. On the shop floor, there are no bosses. Debates continue as to the proper role of the state and the union in the management of the factory. In part of the factory there is a museum dedicated to the workers’ long struggle to take it over.

Joseph Grim Feinberg studies anthropology and folklore at the University of Chicago. Although he now focuses on Central and Eastern Europe, he maintains hopes of returning to an earlier project to study revolutionary culture in Latin America. He is a member of a Chicago-based anti-capitalist

group called the 49th St. Underground and of the socialist organization Solidarity, the latter of which helped sponsor his trip to Venezuela for the World Festival of Youth and Students.