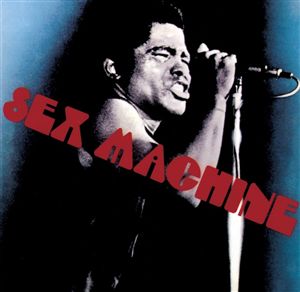

That “Sex Machine” ever got approved for air play is testimony to the stupidity of radio censors. It’s little more than James Brown, the Hardest-Working Man in Show Business (one of several), encouraging his penis to labor just as hard:

That “Sex Machine” ever got approved for air play is testimony to the stupidity of radio censors. It’s little more than James Brown, the Hardest-Working Man in Show Business (one of several), encouraging his penis to labor just as hard:

Stay on the scene

Like a sex machine.

In case you miss the point, the refrain “Get it up!” is repeated after every line.

And then there’s the music. Ravel once quipped that his notorious “Bolero” was “seventeen minutes of orchestration without music.” “Sex Machine,” though shorter, contains no orchestration and even less music than “Bolero.” There’s barely even a chord change. Just drum beats, a guitar part that could be programmed into an original issue 64K IBM PC, and the Godfather of Soul apostrophizing his cock.

And yet “Sex Machine” was the wave of the future. Even today there are plenty of top-forty songs that could have come from Tin Pan Alley, but there is ever more music that shares both its harmonic stasis and its one-track mind.

That the two are linked can be seen by looking to the past. The American popular song of the thirties and forties was about Romance rather than sex. (Older readers may recall the startling novelty of Serge Gainsbourg‘s “Je t’aime . . . moi non plus.”) Romance, whether as love story or seduction, has a narrative and a milieu, and the songs were shaped accordingly.

Now, song form is hard to square with direct story-telling; if things happen during a pop song of the thirties, they usually take place during the verse, or in the pause between verse and chorus. But its stereotyped structure — two choruses, a contrasting bridge, and a final repetition of the chorus — was ideal for exploring milieu.

Listen to the best of the Astaire-Rogers films, especially the two with Jerome Kern scores, Roberta and the wonderful Swing Time, and you’ll hear the bridge used in an astonishing variety of ways to expand the meaning of a song. Its lyrics can mock the pretensions of the opening strain, intensify it, narrate a shift between opening and closing chorus, or even exist in a different tense altogether, as in “The Way You Look Tonight.”

And the harmonic arc of song form draws on the European classical style, its distinctive habit of establishing a home key, disrupting it, and then resolving everything in a recapitulation. A sonata movement reconciles apparent differences into a larger, richer unity than could have been asserted at the beginning. It is a style true to the ideals of the Enlightenment, and it’s fitting that Mozart’s last opera, The Magic Flute, is an explicit parable of integration. So is Fidelio, the only opera Beethoven wrote.

Almost any pop song of the thirties implies the setting and story of a particular romantic narrative. But sex needs and wants neither. Its access to the timeless is at least as appealing as its physical delight, so both harmonic tensions and temporal structure would be out of place. Those imply a location and a process — when in bed we long only to be Here and Now. So it’s perfectly appropriate that Brown’s fusion of musical immobility and the evocation of sexual pleasure would have many successors.

Music without narrative or situational contents, though, does different things to us and we use it in different ways. For pop music is utilitarian; people employ it to think about their lives. You can watch this happening. When I was a teenager, I worked briefly as a night dishwasher in an all-night diner. Around three in the morning the customers were mostly prostitutes, and that summer they were listening to “Hey There, Lonely Girl” and “Love on A Two-Way Street.” These were hardly great songs, but for a quarter they gave a group of oppressed and exploited women some pleasure and even some comfort.

This isn’t a matter of simple escapism. Eddie Holman’s falsetto croon did its bit to soften the harshness of working as a prostitute in Albany, New York, but only when its listeners saw their own lives in its light. There has to be some engagement between the stories you find to describe your life and the stories available on the jukebox. It’s worth something to see your sorrows given a shape and a meaning, and to know that those who share them can sing as well as suffer.

Theorists since Adorno and Horkheimer have insisted that the popular arts only reconcile people to a cruel and inhuman system. This may be true, but it is still enough of a reconciliation to make life tolerable. Our customers at the UN Diner didn’t have many chances to live outside of that system, and those who have the luxury of maintaining a critical distance from the world of capital shouldn’t condemn those who have nothing else handy to get them through the night. The songs worked. People listened to them, sang along, and felt heard and appreciated in small ways. They walked a little more proudly.

Structureless, static music works differently. It provides an escapism that is both deeper and more shallow at the same time. Deeper, because it evokes a state of physical arousal and heightened awareness; and more shallow, because that state exists on its own and can’t be connected with the story of anyone’s life.

The popular song once took the integrating movement of the classical tradition and provided a mollifying gloss on life in a world too much with us. What we’re seeing now is something different: the emergence of an aesthetic world removed from social process altogether. The popular arts of the twenty-first century are becoming substitutes for life in ways that go far beyond the ambitions of Photoplay or the studio moguls of the thirties and forties.

Newer genres of music can be crude and annoyingly obvious; cable access shows are full of indistinguishable hip-hop videos with the guys doing gang signs and the women working it like pros. On the other end of the spectrum is the best hip-hop and a lot of house and club music, which can be absorbing and even intellectually and emotionally rich. But in spite of well-meaning attempts to address social themes, the formal logic of most of this music turns us away from experience. The intricate repetitiveness and harmonic stasis of most hip-hop and the insistent drive and electronically-aided complexity of club music both aim to generate a constant tumescence. When you’re up you leave the world behind; you exist in a dreamworld that floats self-sufficient as a bubble. Whatever its content, though, the dreamworld remains cut off from the rest of your life. The bubble lasts only as long as beat does.

So dreamworld is an addictive drug, and once we imbibe we are left with no desire but James Brown’s. We don’t want to go home. The only thing we want is to stay on the scene. Like a sex machine.

Michael Steinberg is the author of The Fiction of a Thinkable World: Body, Meaning, and the Culture of Capitalism published this year by Monthly Review Press and essays in professional journals in history, music, and law. He and his wife Loret, a photographer and professor of documentary photography, live in Rochester, New York, under the supervision of two domestic medium-hair cats.