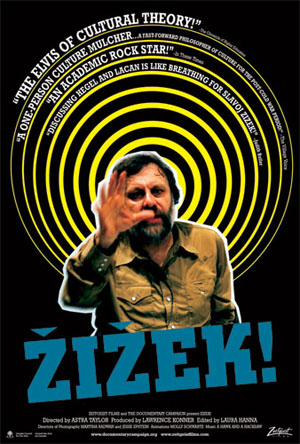

One of the most pleasant (and, for us, unanticipated) consequences of finishing a film is the chance to travel on other people’s tab.  In the coming months, we have invitations to travel and screen Zizek! in venues as far flung as Vienna and New York City, Beirut and Columbia (Missouri, that is), primarily at film festivals but also at a handful of cinemas and universities. In addition to being able to travel the world when we can barely afford rent, participating in film festivals provides us with an unparalleled opportunity to see the latest crop of documentaries, many of which will, unfortunately, never get a proper release.

In the coming months, we have invitations to travel and screen Zizek! in venues as far flung as Vienna and New York City, Beirut and Columbia (Missouri, that is), primarily at film festivals but also at a handful of cinemas and universities. In addition to being able to travel the world when we can barely afford rent, participating in film festivals provides us with an unparalleled opportunity to see the latest crop of documentaries, many of which will, unfortunately, never get a proper release.

For two young documentarians who never went to film school, this is a fantastic chance to study the craft and get to know the ins and outs of the industry. Even better, it offers us countless occasions to see how other, more experienced filmmakers are dealing with some of the problems we ran up against while making Zizek! — from mundane issues like financing and rights clearances to more philosophical questions about the power and limits of cinema as a tool for social change.

This column will be a record of the triumphs and tribulations of bringing Zizek! to the masses, our reactions to the films we see at festivals, interviews with filmmakers who inspire us, and our attempt to get a new documentary project underway.

Poetry versus Propaganda

As we begin to seriously consider our next cinematic undertaking, we often find ourselves grappling with the two poles of documentary filmmaking: the poetical and the political. We want to make films that matter, which address social problems, educate the audience, and inspire action. But we also care about technique and value artistry and beauty. Our favorite films all have an element of ambiguity, leaving room for debate and interpretation. We’re tired of bland, issue-driven films, uninspired camerawork, and didactic messages (even ones we agree with). At the same time, we’re equally suspicious of the tendency to make art that suffers from historical amnesia or political

naiveté, or worse, films that aestheticize suffering and devastation. Too many documentaries shy away from exposing the root causes of social problems by personalizing them.

At the Toronto International Film Festival in September, where Zizek! had its premiere, Laura and I saw an array of films that only made what we call the Poetry-or-Propaganda divide seem all the more entrenched. There were, thankfully, two documentaries that each represent the best of the poetic and propaganda schools

of filmmaking. One is Gary Tarn‘s Black Sun, which is self-consciously poetic. The other is a propaganda offering, Why We Fight by Eugene Jarecki, one of the directors who brought us The Trials of Henry Kissinger in 2002.

Why We Fight

There is no doubt that Why We Fight is liberal propaganda.  It takes its name from a series of pro-war propaganda films made by Frank Capra for the War Department during the WWII, prompting the audience to contrast (what Jarecki sees as) clear reasons for “the Good War” with the George W. Bush administrations’ false reasons for the Iraq War. Running over an hour and a half, it’s a sustained demonstration of a single, straightforward premise that will come as no surprise to the readers of Monthly Review: wars are waged for profit.

It takes its name from a series of pro-war propaganda films made by Frank Capra for the War Department during the WWII, prompting the audience to contrast (what Jarecki sees as) clear reasons for “the Good War” with the George W. Bush administrations’ false reasons for the Iraq War. Running over an hour and a half, it’s a sustained demonstration of a single, straightforward premise that will come as no surprise to the readers of Monthly Review: wars are waged for profit.

Jarecki’s argument revolves around Dwight Eisenhower’s famous 1961 farewell address in which he warned of the “military-industrial complex,” the unholy alliance of the defense industry and the government. While the film purports to ask just how prescient Eisenhower’s warning was, the answer is fairly obvious from the opening scene: Very.

Though his film is clearly liberal, Jarecki tries hard to make a film that won’t immediately alienate viewers who don’t already agree with him. Jarecki employs various techniques to make Why We Fight‘s political message more palatable to centrists and conservatives. The talking heads either command a modicum of respect from the political mainstream — Eisenhower’s offspring, Senator John McCain, and Dan Rather, to name a few — or are recognizable as stereotypical, “real” everyday Americans.

|

For example, there’s Wilton Sekzer, a retired New York City cop whose son died on 9-11. One of the movie’s main narrative threads traces Sekzer’s evolution from a man desperate for revenge — he asks the government to write his son’s name on a bomb destined to be dropped on Baghdad; seeing a decent PR opportunity, the officials oblige — to someone who, after Bush admits there was no connection between Iraq and the terrorist attacks, realizes his grief and patriotism were exploited.

In his attempt to appeal to a broader audience, Jarecki carefully avoids Michael Moore-style self-dramatizing. The director remains invisible, letting his characters do the talking. The film’s tone is serious without being heavy-handed, hard-hitting without seeming overly polemical. It’s also stylistically predictable, following a made-for-television formula (which it was – it’s a BBC Storyville production). Why We Fight cuts from the authority of a government official to a man-on-the-street interview to archival footage to a soundbyte from the nightly news. And then the process repeats itself.

Yet, such a standard format is hardly inappropriate given the subject at hand. Why We Fight is a straightforward explication of the political economy of war, with just enough of a human interest story to draw in a skeptical viewer. It’s not the most beautiful, innovative, or challenging film ever made, but that’s okay because it’s propaganda, not art. And that’s a good thing. At a time when a substantial (though rapidly diminishing) number of Americans still think we’re in Iraq fighting Terrorism under the banner of Freedom, Why We Fight sends a necessary message. Capitalism, the film demonstrates, is at war with democracy. As long as fighting continues to make some people very, very rich, world peace will remain a pipe dream.

— Astra Taylor

Black Sun

All too often, films rely on melodrama in the portrayal of a person who overcomes trauma, as a way of making up for lack of substance. It is rare to stumble upon a project that illuminates growth through tragedy in a subtle and artful way. This is what Gary Tarn achieves with Black Sun, a poetic, intelligent, and innovative documentary about Hugues de Montalembert, a painter and filmmaker who was blinded by two robbers who had broken into his apartment. (De Montalembert has since written an autobiography: La lumière assassinée [Eclipse].) Eschewing traditional visual cues that tell the audience what to think and feel, Tarn gives viewers the space to experience de Montalembert’s story intimately in their own idiosyncratic ways.

Filmmakers, intensely visual creatures, normally capture images first and design sound later to apply to them. Tarn upended conventional filmmaking. Black Sun grew out of de Montalembert’s voice. Tarn first recorded de Montalembert’s words over a couple of days. And he collected images — from America, Europe, and India — while editing the intervews with de Montalembert. Then, Tarn, a musician, composed music for de Montalembert’s narrative. It was only after the aural structure of the film was established when he edited the collected images for the soundtrack. The result of the reversal is transformative. It disciplined Tarn to learn to see — or at least imagine — the world in de Montalembert’s way.

What does Black Sun show? Not one of the images shows de Montalembert. The images, instead, are what the blind artist — still a cosmopolitan who continues to travel and creates films in his mind’s eye — might have seen and might see now. Tarn’s stunning imagery encourages the viewer to contemplate what it means to see — and what is overlooked by seeing eyes. Black Sun demonstrates that, as de Montalembert observes in the film, vision is indeed “a creation, not a perception.”

What does Black Sun show? Not one of the images shows de Montalembert. The images, instead, are what the blind artist — still a cosmopolitan who continues to travel and creates films in his mind’s eye — might have seen and might see now. Tarn’s stunning imagery encourages the viewer to contemplate what it means to see — and what is overlooked by seeing eyes. Black Sun demonstrates that, as de Montalembert observes in the film, vision is indeed “a creation, not a perception.”

— Laura Hanna

Laura Hanna (left) was born in 1976 and raised on the fertile land of the central coast of California. In San Francisco she studied the technical aspects of sound recording, where she also sat in on film classes. Naturally it was only a matter of time before the interests merged. She has worked in film/television in New York City for the past five years doing post-production mixing, editing, sound design, as well as installation and location recording. The following is a partial list of projects she has worked on in the previously mentioned capacities: Road to Paris (CBS, 2002), Shots in the Dark (CTV, 2002), Justifiable Homicide (2002), A Day in the Life of Africa (2003), The Perpetual Life of Jim Albers (Sundance, 2003), Academy Awards Open (Errol Morris, 2003), Hollywood High (AMC, 2003), Some Kind of Monster (Sundance, 2004). She is the editor of the documentary Zizek!. Astra Taylor (right) was born in Winnipeg, Canada in 1979 and grew up in Athens, Georgia. She has an MA in Liberal Studies from New School University and has taught sociology at the University of Georgia and at SUNY-New Paltz. Her writing has appeared in Salon, The Nation, and Monthly Review and her first book, Shadow of the Sixties, will be published by the New Press in 2006. In 2001, she traveled to Senegal to make a short film about infant malnutrition for an African NGO. She then associate-produced Persons of Interest, about the illegal arrest and detention of Arabs and Muslims after September 11th, which premiered at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival. Zizek! is her first feature.