In recent decades, many well-meaning thinkers and activists have peddled or purchased the idea that class conflict has somehow waned or been “de-centered” in the richer nation-states. As workers in these countries have lost more and more power, and as vast tides of wealth have sloshed around in the form of automobiles, shopping malls, and a universe of unimagined convenience goods, many otherwise quite lovely folks have thrown up their hands on the Marxian insistence that class struggle is always going to be the core problem in a capitalist world. As unions suffocate and workers shop and pray and watch “reality TV” rather than fight the power, what good could it be to beat that dead old horse?

Of course, we Marxians — and even Marx himself — are partially to blame for the wide appeal of this facile but enormously damaging intellectual and political mistake. By remaining fixated on “what Marx said,” we have largely failed to see and explain a very simple fact: capitalists have never ceased their class-struggle-from-above at the factory gates, and, in our late corporate capitalist epoch, a great many first-world “popular” and “free time” phenomena are, upon inspection, immersed in elaborate managerial efforts designed to achieve the ultimate aim of all upper-class domination: making ordinary people’s thoughts and behaviors enhance the power and privilege of the ruling class.

Today, the cardinal example of this application of class-struggle-from-above to off-the-job life is the profession and practice of big business marketing. In the United States alone, it is now a 2-trillion-dollar-a-year endeavor. That is roughly equal in size to all spending by the U.S. federal government.

The major premise of big business marketing is the insight, first clearly articulated in the 1920s, that prospective product users (a.k.a. “consumers”) are, in their off-the-jobs hours, susceptible to being influenced by rational, profit-seeking, scientific management.

Not coincidentally, one of the very first corporate leaders to recognize and begin publicizing this fact was none other than Frederick Winslow Taylor, the “father of scientific management.” That shouldn’t be surprising, since what we now know as corporate marketing is nothing short of an attempt to extend Taylorian labor-management techniques into the spheres in which prospective product users make their product-buying decisions and develop their product-using habits.

Not coincidentally, one of the very first corporate leaders to recognize and begin publicizing this fact was none other than Frederick Winslow Taylor, the “father of scientific management.” That shouldn’t be surprising, since what we now know as corporate marketing is nothing short of an attempt to extend Taylorian labor-management techniques into the spheres in which prospective product users make their product-buying decisions and develop their product-using habits.

In both its workplace and marketing forms, modern corporate management does these three things:

- Specialists exhaustively collect detailed data about existing behaviors.

- Specialists and managers very carefully analyze behavioral data and then formulate strategies for using commands, images, and redesigned places and spaces to profitably alter future behaviors.

- Repeat this process, ad infinitum.

In the marketing profession, pursuit of these core Taylorist activities is directly analogous to what workplace engineers have long done to the job routines of corporate employees. Where industrial engineers time and photograph the minutiae of workers’ physical and mental job performances, big business marketing deploys armies of experts to conduct “marketing research,” the purpose of which is to record the physical and mental performances of prospective product purchasers. Just as industrial engineers and corporate labor managers then confer on how best to profitably change existing job instructions and environments, so do marketing experts and corporate managers then confer on how best to profitably change existing “consumer” instructions and environments. Finally, the vast and always rapidly growing universe of marketing events, promotions, advertisements, PR efforts, and product packages represents, from the ordinary citizen’s perspective, exactly the same thing as the Taylorized workplace: a trap designed by the ruling class, which we non-capitalists cannot but enter, if we wish to live.

A standard gripe in advertising has always been department store mogul John Wanamaker‘s quip that “I know that only half my advertising works. The problem is I don’t know which half.” The same truth applies to marketing. Because prospective product users are not as coercible as hired workers, marketing is not nearly as effective as on-the-job management. Nevertheless, even if only half of big business marketing works, that means corporate capitalists are achieving a trillion dollars’ worth of off-the-job behavior modification in the United States every year!

There is a mini-industry devoted to teaching people how to “read” the meanings of big business advertisements. This is certainly a vital citizenship skill. Seeing the true intent and method of an ad’s creator allows you to make better personal and political choices. Unfortunately, many of the scholars and activists who specialize in “media literacy” tend to obscure, rather than clarify, the ulterior purpose of the imagery they try to criticize. Would-be critics churn out morasses of verbiage about “consumer culture,” “fables of abundance,” “metaphorical maps,” and the like in their endless exegeses of

advertisements, but the one and only purpose of any corporate capitalist advertisement is to alter the behavior of the “target” audience in favor of the advertiser’s bottom line — i.e., in favor of the wealth of the firm’s shareholders.1 Advertising is neither more nor less than a new form of a 6,000-year old enterprise: class coercion from above.

The first and best thinker to recognize this crucial fact was the badly underrated and usually woefully misread Thorstein Veblen. A choppy but powerful and often funny writer, Veblen analyzed the ways in which, despite capitalists’ claim that their class’s eventual dethroning of kings ended history’s train of arbitrary power regimes, in reality, modern corporate investors derive their powers and privileges from the same old foundations as

their predecessors’: applied “force and fraud.” Behind their formally free contracts and optional leisure-time offerings, Veblen insisted, modern capitalists and their top managerial agents orchestrate an “increasingly covert regime” that differs from old-fashioned class tactics in form, but not in purpose: behavior modification of underlings. Once we grasp Veblen’s simple but extraordinarily apt point, we can see that every single corporate capitalist advertisement is a vehicle of one or more of the following classic forms of applied “force and fraud”:

- a threat

- a false promise

- a trick

- a mental implant

The classic and most obvious case of a threat ad is this:

The message here, of course, is “if you don’t lay out the extra cash for Michelin tires, you are going to kill your own child.” Too obvious and crude to fool anybody? Nope. “We are so proud of the impact the baby campaign has had over the years,” remarks a Michelin “brand manager.” “It’s rare for an advertising campaign to have this kind of longevity and influence on an industry.”

False promises are so rife in advertising that it’s almost silly to select a single example. Beer ads promise peak party experiences. Sneaker ads tell you that you’re a superstar if you wear Air Jordans. The right cosmetics will make all women Halle Berry. Car commercials promise you your neighbors’ envy and invariably show the vehicles gliding along empty forested highways or scaling spectacular Southwestern mesas, not idling amid potholes in rush-hour traffic jams.

Sometimes the puffery gets downright ridiculous. Medical and quasi-medical ads often suggest that a single pill is all that stands in the way of perfect health or even miracles such as this one:

|

|

“Natural male enhancement” means, of course, the Holy Grail of macho (pun intended) pin-heads everywhere: a bigger schlang. Never mind that every competent urologist says that no pill could ever trigger such a teenager’s dream.

Tricks are another common advertising method. Insurance ads promise to save people “up to” X amount of money, while the question of your chances of actually getting “up to” such a level is never raised. On Saturday mornings, my son and I constantly mutter to ourselves about how all the corporate sugar-bomb breakfast cereals are always “a delicious part of a balanced breakfast.”

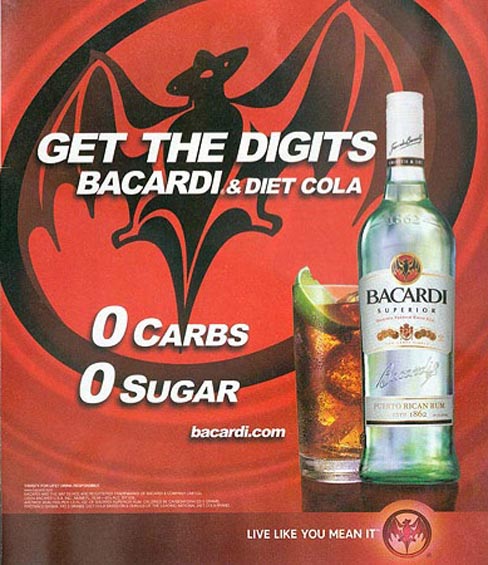

One of my favorite examples of trick ads is this one:

“0 Carbs” and “0 Sugar.” What fantastic news! Rum is now a health-food/diet drink, according to the Bacardi corporation! Nothing like 5 or 6 Cuba Libres to burn off those unwanted pounds! But, of course, this is all simply a trick that exploits popular ignorance of human biochemistry. In reality, the human body stores energy (and makes fat) first from acetates, then from sugars, then from fats, and finally, if necessary, from proteins. The acetates, in other words, are the body’s preferred raw material for quickest fat production. And what does ingested alcohol turn into upon liver metabolism? You guessed it: acetate! Thus, if you want to gain weight as rapidly and efficiently as possible, drink lots of alcohol.

The other major tactic in corporate capitalist advertising is mental programming. Through ubiquity, repetition, titillation, and surprise, big business marketers aim to “alter the mental agendas” of their “targets.” If you doubt the importance of this method, take a look at the surveys comparing American schoolchildrens’ knowledge of corporate icons with their knowledge of other things. That’s not a close contest.

In the most successful cases, research has demonstrated that advertising repetition can even train the human brain to associate mere colors and shapes with specific corporate brands. Marlboro cigarette marketers, for instance, know that their placement of the Marlboro “red roof” in sports arenas and auto-racing tracks around the world prompts semi-conscious loyalty shifts in favor of their brand of death-sticks. They also know that, even when a region bans explicit advertising, their past successes mean that merely painting a race car “Marlboro red” is likely to be a profitable undertaking:

When, despite the European Union’s ban on tobacco advertising, Marlboro paid Ferrari Formula 1 Racing to repaint its European race cars “Marlboro red,” it yielded the above appearance. Did it work?

[T]elevision viewers are certain to respond to car designs that echo Marlboro’s bold red packaging and Lucky Strike’s circle, says Jez Frampton, chief executive officer of London-based brand consulting firm Interbrand. The firm rates Marlboro as the world’s 10th-best-known brand.

“People will spot it, without a doubt,” says Frampton, 40. “Design is powerful. That’s why companies spend a lot of money on corporate identity.” (Alex Duff, “Formula One Races Past EU Tobacco Ad Ban Using Familiar Colors ,” Bloomberg, 29 July 2005)

It you can memorize these four tactics — threats, false promises, tricks, and thought implants — you will have 95 percent of what you need to powerfully dissect and explain any corporate advertisement.

That confirms the importance of the historical materialist eye. In days of yore, feudal lords and priests threatened serfs with fiery Hell. Roman patricians assured plebeians that bread-and-circuses and “Romanness” would lead to the best of all possible worlds. Emperors and overlords everywhere peddled utter nonsense about “noble” blood. Imperial state religions incessantly harangued downtrodden masses to learn and think “correct” thoughts. Now, though the hand of the masters is, as Veblen noted, “increasingly covert,” looking at that hand shows that nothing essential has changed. Then as now, the comfortable class bullies and baits us into spending our lives performing routines that exist to feed its arbitrary and unfair and destructive pleasures. Hence, when you stop to notice it, your TV and your magazines and your mundane experiences of “free time” are trying to yoke your energies to power just as surely as did the whips and henchmen of olden, more naked, days. By educating ourselves and others about the nature and logic of elite efforts on this marketing front, however, we can help begin to restore hope for eventually conquering its masters. Product users of all countries, unite! We have nothing to lose but our chains!

1 Alfred D. Chandler, the nation’s foremost business historian, remarked that, despite much propaganda to the contrary, a numerically tiny elite of “established households . . . remain the primary beneficiaries” of corporate capitalism.

Michael Dawson works for pay as a paralegal and sociology teacher in Portland, Oregon. He is presently writing a book, Automobiles Ueber Alles: Corporate Capitalism and Transportation in America, forthcoming from Monthly Review Press.

Michael Dawson works for pay as a paralegal and sociology teacher in Portland, Oregon. He is presently writing a book, Automobiles Ueber Alles: Corporate Capitalism and Transportation in America, forthcoming from Monthly Review Press.