“. . . what a state of society is that which knows of no better instrument for its own defense than the hangman, and which proclaims . . . its own brutality as eternal law? . . . [I]s there not a necessity for deeply reflecting upon an alteration of the system that breeds these crimes, instead of glorifying the hangman who executes a lot of criminals to make room only for the supply of new ones?” — Karl Marx, 1853

The State of California is preparing to execute Stanley Tookie Williams at one minute past midnight on December 13.

In many ways, Stan’s case is exceptional. At the time of his arrest in 1979, accused of four robbery-related murders, Williams was effectively Public Enemy Number One in the city of Los Angeles. In 1971, when he was just seventeen years old, Stan co-founded the Crips in South Central LA. Originally established for self-defense, the Crips rapidly became the most feared African-American street gang in the city.

After his 1981 conviction, at first Williams continued his gangster life behind bars on San Quentin’s death row. But after several years in solitary confinement, and in the face of relentless hostility from the prison authorities, Stan began to rehabilitate himself. At some risk to his safety from other gang members, he publicly renounced his gang connections and apologized for the pain and harm that his past actions had caused. Since that time, Williams has dedicated himself to combating the influence of street gangs and doing whatever he can from his tiny prison cell to end gang violence.

Since the mid-1990s, Williams has written nine books for children, attempting to de-romanticize gangs, crime and prison. One of them, Life in Prison, has received two national book honors, including an award from the American Library Association. It has been used in schools, libraries, juvenile correctional facilities, and prisons throughout the United States and around the world, including in Pollsmoor Prison in Cape Town, South Africa. Stan has also recorded anti-gang public service announcements for radio that have aired on stations across the United States.

More than 70,000 people have sent emails to Stan’s web site, expressing appreciation for his work, with many saying they have opted not to join gangs or have withdrawn from gang membership as a result of reading his books or hearing his voice. Messages like this one are typical:

My name is J______ and I was a member of a Los Angeles street gang. I would just like to let you know how big of an impact your story had on my life. Your works have made me realize the self-destruction that my involvement in a gang was causing. I love you for that. I pray for you every night. I wish you the best of luck on any further works. Thank you for saving my life.

A fourth-grade teacher in Philadelphia writes:

I first borrowed one of your books, Life in Prison, from the library, but it became so consistently overdue with the children asking me to read and reread it, that I went out and bought all the children’s books and Life in Prison, so I wouldn’t have to worry about holding the library book for too long. I have used all your children’s books and they have so DEEPLY affected my students in a positive way — and it gets them reading (ha! — a teacher’s secret motivation). Some of the students started to open up and talk about relatives in prison — issues they were ashamed of — which was good. They relate to your messages in many ways and are at an age where they can make important choices that will affect the rest of their life. You address those choices, and you have unromanticized prison for them. They never heard of gladiator schools, but many thought prison as being a hip place. Now they are rethinking it.

Last year, Jamie Foxx played Stan in Redemption — a TV movie about his life. Shortly after seeing it, gang members in Newark, New Jersey negotiated a truce based on the “Tookie Protocol for Peace: A Local Street Peace Initiative,” posted on his web site. Before signing the peace treaty, the gangs had been responsible for 34 murders in the first four months of 2004 alone. In the months after the agreement, gang-related killing in Newark stopped.

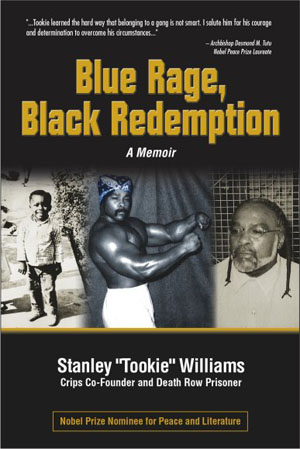

The Observer newspaper in London reported in November 2004 that Stan’s anti-gang initiatives have now been extended to Britain. In London, where there is a significant street gang problem, the hip-hop music industry is featuring him in an anti-gang advertising campaign in magazines, and his recently published autobiography (Blue Rage, Black Redemption) is being sold in music stores alongside hip-hop CDs.

At a conservative estimate, Stan has saved hundreds of lives over the past few years. Because of his extraordinary work, Stan was nominated for the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize by a group of Swiss parliamentarians, after his anti-gang message helped to defuse a violent gang conflict in that country. I have re-nominated him for the Peace Prize four times since then, and will do so again later this month.

A Case Study of What’s Wrong with Capital Punishment

Stan’s story is without doubt in many respects exceptional, and this has made him San Quentin’s best-known inmate. Yet in other respects, his story is utterly unexceptional and could serve as a near perfect case study of what’s wrong with the death penalty in the United States.

The Campaign to End the Death Penalty lists five reasons to oppose capital punishment. Stan’s case illustrates each one of them.

1. The death penalty is racist.

While they make up only 12 percent of the overall population, nearly 42 percent of those on death rows around the US are African-American. A recent study of capital punishment in California revealed that suspects convicted of killing whites are three times more likely to be given the death penalty than those convicted of killing blacks, and four-times more likely than those convicted of killing Latinos.

Stan’s original trial was moved from the city of Los Angeles itself to Torrance, a conservative area with few African-Americans. The prosecutor, Robert Martin, who had a long history of targeting young men of color, removed all three African-Americans from the jury pool. In his summing up he compared Stan to a Bengal tiger in the San Diego Zoo, suggesting that he would behave like a wild animal if he were allowed to return to his “habitat,” meaning South Central Los Angeles. The California State Supreme Court later reprimanded Martin for similar racist practices in two other cases and reversed the death sentences in both of them. By the time Stan’s conviction came up for appeal, however, the political climate had changed. Earlier this year, the Ninth Circuit rejected his appeal, even though nine judges issued a withering dissent, condemning the “blatant, race-based jury selection” in Williams’ original trial.

2. The death penalty punishes the poor.

No wealthy person has ever been executed in the United States. Capital punishment is reserved for those, like Stan Williams, unable to pay for a high-priced lawyer. As California assembly member Mark Leno noted recently:

A frequent reason for reversal in death-penalty cases is ineffective assistance of counsel. A Columbia University study found that nationwide, 68 percent of all death-penalty cases were reversed on appeal. Minimum standards for defense counsel only took effect last year in California. Most inmates now on Death Row were tried at a time when attorneys did not qualify under these standards and were not trained in death-penalty defense. (“Avoiding Ultimate Mistake in Applying Ultimate Punishment,” San Francisco Chronicle, 14 November 2005)

The California Commission on the Fair Administration of Justice has been established to examine flaws in the administration of the death penalty, and Leno is supporting legislation that would enact a moratorium on capital punishment until it has done its work. But the bill is not due to be voted on until January, which may be one reason why Stan’s execution date has been set for December.

3. The death penalty condemns the innocent to die.

Stan has always maintained that he did not commit the crimes for which he was convicted. The main evidence against Stan was the testimony of informants who claimed that he had confessed to them. All of these “witnesses” were facing serious felony charges and had strong motivations to make a deal with the police to reduce their own sentences. In fact, in its 2002 ruling, the Ninth Circuit admitted that these informants had “less-than-clean backgrounds and incentives to lie in order to obtain leniency from the state in either charging or sentencing.”

Since the original trial, another prisoner has come forward to say that he witnessed one of the informants being given the file on Stan’s case by members of the Sheriff’s Department so that he could learn details about the murders.

None of the physical evidence found at the two crime scenes, including fingerprints and a boot print, matched Stan. A witness’s description of a person seen leaving the scene of one of the crimes did not fit him either. A shotgun shell supposedly matched a weapon he had bought several years earlier, but that gun was in the possession of a couple that was also facing serious felony charges. After they claimed that Stan had confessed to them, the investigation against them was dropped.

Now that Stan finally has competent legal representation, his lawyers have reinvestigated the evidence used in the case and found that it is even less adequate than previously known. According to one expert, for instance, the ballistics analysis used to identify the shotgun shell was nothing more than “junk science.” Stan’s lawyers have filed a new appeal with the California Supreme Court, pointing out many holes in the case against him, and the police and prosecutorial misconduct that convicted him.

4. The death penalty is not a deterrent to violent crime.

If the courts refuse to reopen Stan’s case, his only hope is clemency from Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. But Schwarzenegger is an enthusiast for capital punishment. He has refused clemency in two other cases and has claimed that the death penalty is “a necessary and effective deterrent to capital crimes” (Henry Weinstein, “Gov. Is Asked to Spare Inmate,” Los Angeles Times, 9 November 2005).

But despite attempts by conservatives to use statistical legerdemain to prove otherwise, the claim that executions deter crime is a myth. The largest number take place in the South, which has the country’s highest murder rate, the fewest in the North East, which has the lowest.

5. The death penalty is “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Stan Williams has been sitting on California’s death row for over twenty-four years, with the threat of execution hanging over him. As Albert Camus noted in “Reflections on the Guillotine” in 1957, “The devastating, degrading fear that is imposed on the condemned for months or years is a punishment more terrible than death,” and typically far more terrible than any crime the condemned person is accused of committing.

The Politics of the Death Penalty

The death penalty in the United States is not an instrument of justice, but a political tool. In 1972, in Furman v. Georgia, the US Supreme Court, invalidated all existing death penalty laws because they were being applied in a discriminatory and arbitrary manner. This was perhaps the last significant victory of the civil rights movement that had overturned legal segregation in the 1960s.

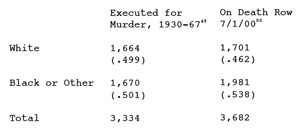

| Compare, for example, the racial characteristics of those executed for murder from 1930 to 1967 to the racial characteristics of those on death row today:

So, the proportion of non-whites among those executed for murder between 1930 and 1967 was 50 percent; today the non-white population of those on death row has risen to 53.8 percent. In short, if we focus attention on death sentences for murder, we can see that the racial disparities in today’s death sentencing are even worse than in the years before Furman. (footnotes omitted, Michael L. Radelet, “Twenty-Five Years after Gregg,” 1 September 2000, pp. 22-23) |

Four years after the Furman decision, however, the Court, in Gregg v. Georgia, approved new and more elaborate laws that supposedly avoided the problem of arbitrariness. This change of heart has to be understood in the context of the response by political and economic elites to the movements of the 1960s, in particular the civil rights movement and the more radical movement for black liberation that emerged out of it.

The anti-racist movements of the 1960s shook US society to its core, and played a critical role in precipitating the mass movements against the Vietnam War, and for women’s liberation and gay liberation. The result was a general radicalization unprecedented since the 1930s. This came as a tremendous shock for US ruling class, which thought it had buried the left forever in the 1950s.

Ruling-class politicians looked for a way to respond to the mass upsurge. Various strategies were tried, from political assassination and repression, to attempts to co-opt the movement. One important element of their response was to use the issue of crime, both to justify repressive policies and to propagate more subtle ideological messages. According to the criminologist William Chambliss:

The politicization of crime by conservative politicians occurred at a time when the country was deeply divided over the Vietnam War and civil rights. In this historical context crime became a smoke screen behind which other issues could be relegated less important. Crime served as well as a legitimation for legislation designed primarily to suppress political dissent.

Crime was also a coded way of talking about race. “Law and order” was central to Nixon’s “Southern strategy” for winning the presidency in 1968, for example. The aim was to build a Republican majority by making racist appeals to Southern voters who had traditionally voted for Democrats. As H.R. Haldeman, Nixon’s chief of staff, wrote in his diaries soon after the election, “[the President] emphasized that you have to face the fact that the whole problem is really the blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognizes this while not appearing to.”

This right-wing ideological offensive coincided with the political exhaustion of the movements of the 1960s. By the mid 1970s, mainstream politicians who were prepared to say that crime is rooted in social problems or to stand up for the rights of defendants in criminal trials were becoming few and far between. The return of the death penalty in 1976 was an early result of this political offensive. Indeed, it can be plausibly claimed that the death penalty, with its extreme racial bias and conservative ideological trappings, represents the “Southern strategy” in its most concentrated and ugly form.

The death penalty has always been a tool of class and racial oppression, the two roles being intimately connected. One study of the history of capital punishment in Texas concludes, for example, “Slavery, criminal justice, lynching, and capital punishment are historically closely intertwined in the United States.”

Sometimes, the death penalty has been used as a method of direct political repression — from the Haymarket Martyrs in the 1880s, to Joe Hill in 1916, to Sacco and Vanzetti in the 1920s, to the Rosenbergs in the 1950s, to Mumia Abu Jamal today. But the main reason why the death penalty is a political issue is because it is part of a broader political offensive.

Capital punishment in the US has very little to do with justice, or preventing murder, or protecting the public. It is a political tool of the ruling class that has proved highly functional as a means of reinforcing racial divisions, diverting attention from serious social and economic problems, and pinning the blame for crime on abnormal individuals rather than on the underlying social conditions. Stan Williams, who grew up facing racism and poverty, knows this well. As he puts it in his autobiography, he was “a normal child in an abnormal environment,” soon branded a failure at school and victimized by the cops.

Saving Tookie

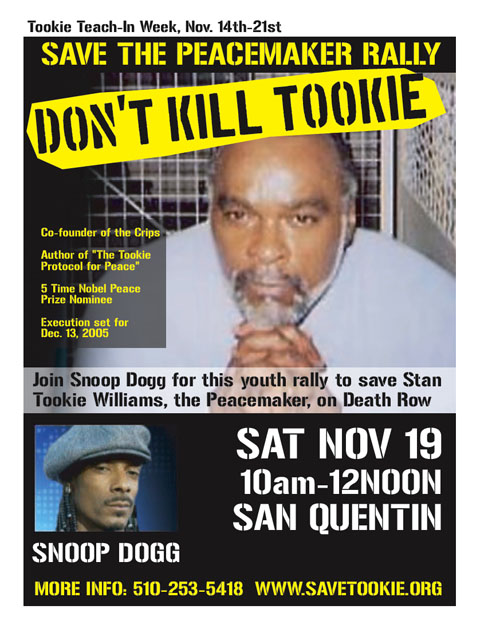

Time is rapidly running out for Stan, and the only thing that can now save his life is a mass campaign to pressure the courts and the Governor to halt his execution. Already, over 30,000 people have signed petitions calling for clemency. November 14-18 was a week of teach-ins on Stan’s case in schools and on campuses around the country. On November 19, rapper Snoop Dogg is leading a rally to “Save the Peacemaker” at the gates of San Quentin. November 30 has been designated a day of action on Stan’s behalf. Whether these and other activities will generate enough political momentum to prevent his legal lynching remains to be seen. But anyone who wants to help should visit SaveTookie.org to find out what they can do. There is no time to waste.

Phil Gasper is Professor of Philosophy at Notre Dame de Namur University in California and a member of the Campaign to End the Death Penalty. He has nominated Stan Williams for the Nobel Peace Prize four times.