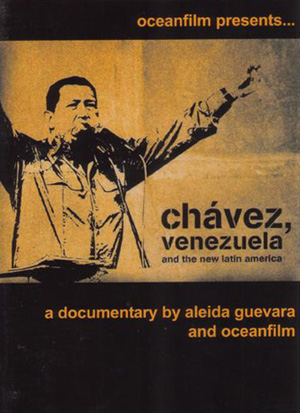

Chávez, Venezuela, and the New Latin America is a modest documentary directed by Che Guevara‘s daughter, Aleida Guevara. Through extensive interviews with Hugo Chávez Frías, president of Venezuela, the film chronicles the coming to consciousness of the Latin American leader, describes the U.S.-backed attempt to topple his government, and raises the question of what a Bolivarian revolution might mean for Latin America as a whole.

Chávez, Venezuela, and the New Latin America is a modest documentary directed by Che Guevara‘s daughter, Aleida Guevara. Through extensive interviews with Hugo Chávez Frías, president of Venezuela, the film chronicles the coming to consciousness of the Latin American leader, describes the U.S.-backed attempt to topple his government, and raises the question of what a Bolivarian revolution might mean for Latin America as a whole.

Chávez, the main focus of the film, comes across as a warm, nearly transparent figure. Confessing an early desire to become a baseball star, Chávez describes his entry into the military academy as a way of getting to Caracas. But the proposed one-year stay turns into a seventeen-year commitment to the military, which Chávez credits with teaching him the history of his country and its relationship to the old Spanish empire as well as to the new U.S. overlord. Chávez speaks feelingly of the caracazo, the wave of protests (1989) against IMF-imposed austerity, which pitted the army against the Venezuelan poor and left thousands dead. This event, which marked a turning point for Chávez and others in the military and which he calls a “curse upon the army,” sowed the seeds that were to germinate in Chávez’ own coup against the government in 1992. Imprisoned for two years, he continued his education, reading Fidel and Negri among others. He credits those years of study and discussion (with others who were imprisoned with him) for helping him formulate the course he has followed since his release: creating a revolution from the ground up. His social and economic programs — massive literacy, health, and political campaigns — are aimed to transform the mass of the Venezuelan poor and working class into citizens who are able to work together to build a future of their choosing.

The film also presents interviews with a few of the ten thousand Cuban doctors who now work in Venezuela, bringing medical care and training to the poor. The film does not discuss the right-wing opposition to Chávez, but does examine in some detail the events around the attempted coup against Chávez, and the role of the army and of the people in the street in defeating that attempt.

Although the film takes Chávez as a key figure, it is less interested in hero-worship as it is in using him as a representative figure. What he comes to represent is the indigenous Latin American who comes to understand how colonial rule has shaped his country and his continent and who decides not to be complicit in continuing to support that rule under the guise of “independence.” In watching the film, we come to understand that the Bolivarian revolution, as it is being worked out in Latin America, is a progressive demand with two aims: one, to restore to the poor a sense of dignity, a sense of their right to a decent, free life; second, to bring about the realization that unity means strength.

In the discussion that followed the film, a man who recently returned from Venezuela spoke passionately of seeing that new sense of diginity in people; it must have been a similar feeling that impressed Orwell when he described the waiters in revolutionary Barcelona refusing to accept tips. Although there are many political parties in Venezuela, and many of these of a leftist bent, what they report to have learned is the importance of working together. “We fight and argue continually,” he reports them saying, “But, we have learned to be united in action, and as a result we win, and we win, and we win!”

For a copy of the film and of the book that chronicles additional material from Chávez interviews, go to LeftBooks.com.

J.A. Bujes is a technical writer who lives in Oakland, California.