I spent three of my formative years working for McDonald’s. As if that were not bad enough, it was a tiny, cramped little store, tucked inside of a Wal-Mart. If simply living in America is being in the belly of the beast, as Che Guevara said, then I was most certainly right at the beast’s bloated, cholesterol-laden heart.

It was my first job, and I did a lot of growing up there. It was also the time of a radical shift in my own thoughts and views of the world. At eighteen, I was cynically apolitical and very disaffected. At twenty-one, I was a proud socialist.

I first started work there when I was eighteen. It was a very small McDonald’s, with usually ten to fifteen employees. The employees became a tight-knit group, fiercely loyal and genuinely friendly towards one another. I was hired in as a general employee and I ended up working every position. By the time I left, I had been made a shift manager.

Inside that store, I saw countless abstract scenarios that one often reads about actually being played out in harsh reality. When I started, there was only one local Wal-Mart. When I left three years later, there were three. There were workers who had been in the McDonald’s for years, with no chance for growth or advancement. In the Wal-Mart, when the only female manager became pregnant, she quit, never to return to the boys’ club. I met full-time Wal-Mart and McDonald’s employees who had to collect food stamps to get by. I saw the McDonald’s owner buy three brand-new SUVs in three years — his annual gift to himself. And I was there when the supervisor was caught embezzling at least $150,000 to pay off gambling debts.

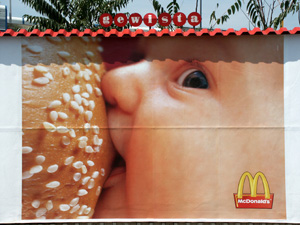

The work itself was generally tolerable, except the constant smell of grease . . . and the bigger picture of which it was a tiny part. For example, I would help unload the supply truck every week. Each truck delivered hundreds and hundreds of pounds of hamburger meat. These stacks of meat in the freezer were tolerable to handle, if that was all I cared to look at. But if I began to wonder where the meat came from, well, there was some trouble. Were we helping to chop down the rainforest to raise and slaughter cows? And what were we doing to customers who bought it? How many clogged arteries and heart attacks were directly linked to the Big Mac?

That was the biggest shift in myself. I began to cultivate a world view coupled with a conscience. The pace of this cultivation was quickened in 2004 with the presidential election. For the first time, I felt like I had the power to help make a difference, to get Bush out of office. So I campaigned for Kerry. I began engaging people, including co-workers, in political discussion. And, eventually, I began the most important aspect of my growing up: I began applying my beliefs as well as the critical tools I had learned to my everyday life.

I finally quit McDonald’s in July of 2005, after a protracted dispute about my lack of raises. I had had enough of working at a place that I referred to as “the outpost of empire.” I took some time off to myself upon leaving and found my whole attitude lightened a little. It felt as though a moral burden had been lifted from me. I still keep in contact with a few people from McDonald’s. Some have moved on while others still work there. They remind me of how little has changed inside the little McDonald’s, and why so much has changed inside of me.

From inside that Wal-Mart, I saw the culture that was being bred, the culture that said that nothing mattered but the low cost. Never mind the sweatshop conditions of workers overseas who were making the goods. Never mind the violence of a corporation that puts the need of people below the needs of the bottom line. We call the culture propagated by the Wal-Marts and McDonald’s restaurants “a consumer culture.” The word “consumer” comes from the Latin verb consumere, which originally meant to “devour,” to “waste,” to “use up” destructively. Consumption is today indeed eating up the lower and middle classes, who make up the majority of “consumers,” and laying waste to what could be a world based on love and equity.

The bottom line has no room for love and equity. Business classes can teach about market shares and macro-economics, but their math cannot teach justice. It just won’t compute.

Andrew Rihn says that he feels “a sense of awe” looking back and seeing the rich history of the left, and he looks forward to where the new American left is going.