The clouds quit teasing, gave us a hard rain with long rolls of thunder and lightning sky-splitters. We hid out in the hay sheds, shifted a few bales around to make the stacks look a little neater. When the rain quit we went to work in the fields, propped bales endwise against each other so they’d dry quicker.

Next morning the air was warm, but with a light and steady wind. Lester was late again, almost an hour this time. Enos and I had to hustle for a while, being one man short. Wasn’t long before we saw Harker driving across the fields to where we were. He was upset, had been roving all over his empire, worried about wet hay, and over at Horse Creek, Harker’s other spread, a baler had broken down.

Enos tried to calm him down. “This hay’ll store just fine, Ed. Even in the best years you lose some.”

Lester showed up, running from where he’d parked his car. “Car trouble,” he said, and went right to work, but it was the last straw for Harker. He went up to Lester, said, “Be late one more time and you’ve had it.”

Lester couldn’t stand reprimands, it was something he’d never learned. He yelled back, “I told you, goddamn it, my goddamn car, battery went dead, had to charge it.

Harker waggled a finger at him and stomped off to his pickup and lit out. The way he hunched over the wheel and bounced the truck across ditches in second gear showed us his visit to us hadn’t helped him the least bit.

Vern and Maury and Preacher got their load made and drove on in. By the time Enos and Lester and I got to the sheds Vern and them had stacked their bales and were passing around a waterbag. Harker was there next to his pickup, writing in his little black notebook. Enos backed our truck in. When Lester saw Harker he got riled up all over again, cussed him out in a low growl that only I could hear, and then, without waiting for Enos or me to get to the rear end to receive bales, Lester started throwing them. They landed all whopper-jawed and it was easy to see that Lester was trying to get every last one of them to split open. A lot of them did. Enos yelled at him to quit, but Lester’d gone hog wild. Harker looked up from his notebook, hustled over to Lester. “That’s it,” he said. “You’re finished. Follow me to the house, I’ll give you your check.”

Lester dropped his hooks on the rack, jumped off and ambled to the nearest post and leaned against it, made like he was looking out at the scenery, acting as if nothing much of any importance had happened, but I knew otherwise. He needed the job, his older brother being married and gone to Utah where he had his own bunch of troubles and Lester’s sister still in grade school; his mom’s job at the convenience store was below minimum wage. His dad had been a trucker. A wild one, people said. His rig jackknifed on that bad stretch of I-80 east of Laramie.

Lester and I had that in common, no Dad. Mine had died five years back, when I was eleven. Dropped dead, heart attack at the Jim Bridger power plant where he had a fairly good-pay job. I guess you could say that since last year when my brother went off and landed a job in Green River, I was what you’d call the man of the house.

Harker went to his pickup and drove it as close as he could get to the broken bales. He jumped out and took the time to give each of us a mean look, then commenced tossing those bales into the pickup. I supposed he planned on feeding them out to the milk cows and calves down at headquarters. He must have known the sheds already had a good number of broken bales sort of patched up somehow or other and tucked in with the others.

I went to help out, but noticed Vern and Maury and Preacher standing still and Enos was fishing out his big turnip watch. Something going on. Harker saw it too. He straightened up from his work, jabbed a finger at me, said, “I could use a little help here, Sandy.”

I took another couple of steps and so did Preacher but Maury’s hand shot out quick as a rattlesnake, grabbed Preacher’s belt and Preacher lost his balance and grabbed at Maury and the two of them teeter-tottered and then you could see they decided to stretch it out, horse around. They were buying time.

Harker barked at me. “Sandy, you’ve been turning into a fine, steady hand and I’ve noticed that, but don’t you go to thinking I can’t find somebody else.”

I have to say, I appreciated that. Bucking bales was my first man-size job and nobody’d ever given me any encouragement in it, not that I’d ever expected any, but there it was, Harker laying on praise. But then he turned a hard glare onto old Enos. Enos needed his job too, and Lester sure as hell wasn’t any pet of his, not after the way Lester had been treating him.

Enos came up to me as if he was on the way to Harker’s pickup, but then he hitched his levis and adjusted his belt and leaned into my face, the brim of his hat blocking my view of Harker. Enos’s eyes were rounder than usual, not tucked away in wrinkles, and his eyebrows were up, but his eyes, my god, those eyes were drilling me. I stared back, sort of hypnotized and then Enos’s hat brim tilted and I noticed Vern finding himself a comfortable seat on a bale, and Maury, the one who’d told us solidarity was just a word, you had to give it legs, he was just standing there next to Preacher not putting any legs on anything I could see, but then, from the look on Maury’s face, I knew that Enos was drilling him like he’d drilled me and Maury knew he’d have to call or fade. He took a seat on a bale. My turn, that was clear enough. I put out a miserable little mumble. “Lester’s a good worker.”

Harker let that pass, looked up at Preacher. What he got back was a little nod, a nervous quirk of his neck, off kilter, about half past four. Enos clicked shut the lid of his turnip and put it away. Never had that click sounded so loud. Harker turned on Enos and I thought, “Okay, here we all go, every last one of us.”

But Enos got in ahead of Harker. “Lester’s a pain in the ass, Ed, no question about that and I’m one to know, after what all’s gone on out here that you don’t know a thing about, but he puts out the work, I have to say that. Him and Sandy both. You want a good hay crop this year, I’d say youve got the right crew for it.”

Harker gave out a big sigh. “Look at this mess here.” He swung his arm at the broken bales. “Lester did that. Temper tantrum, goddamn childishness and I won’t have it.”

Enos took a long gander out into the weather gap. Tall clouds with black bottoms. “Another soaker on the way,” he said.

Harker looked that way. “Christ on a crutch.” He kicked at a bale. “I can’t have Lester coming in late all the time.”

Preacher said, “I’ll see to it.”

Harker gave Preacher a mean smile, shook his head. “Sorry, Jared. I happen to know your wife uses the car.”

“No problem,” Maury said. “I’ve been giving Jared a lift from town, been picking up Enos too, since last week, his truck’s in for heavy repairs, and Sandy meets me in town and Vern lives on my way out here. One more in the bed of my pickup, no problem.”

“Like I promised,” Preacher said, “I’ll see to it. You got my word on that.

Harker gave a big sigh and bent down and picked up half a bale and threw it into the pickup’s bed. “Jesus wept,” he said, “I don’t know why I bother.”

Savng Harker the embarrassment of re-hiring Lester, Enos turned around and shouted. “Lester, get in here. We got work to do.”

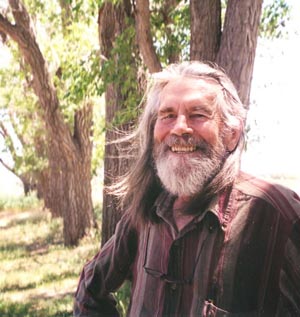

Martin Murie grew up in Jackson, Wyoming; served in the U.S. Army (infantry); studied at Reed College (BA, Literarture and Philosophy) and University of California (PhD, Zoology); taught life sciences at University of Califronia, Berkeley and Santa Barbara, and Antioch College. He retired early, to write. His novels Losing Solitude (1996) and Windswept (2001) were published by Homestead Press and Red Tree Mouse Chronicles (2000) by Packrat Books.