When Harker sold off the hay ranches, the new owner, a super-rich businessman from Denver, kept Lester on as maintenance man. This owner, Christopher Bane and his wife Audrey set themselves up in Harker’s old headquarters ranch and right away started drawing up plans for a big house on the sage bench across the creek from Harker’s layout. Meanwhile, Lester got busy with the cranky well pump and oil heater and putting horse stalls in the barn and a lot of other things that needed doing. He enjoyed the work, being independent, not having Harker breathing down his neck.

One day around the middle of July, Bane came out on the front porch and called Lester up from the corral, told him he’d decided to keep fifty acres as his private living space and cut the rest of the ranch into ranchette parcels. It would mean extra work for Lester, he’d be called on to take prospective buyers out and around, show them the lay of the land. In compensation, Lester would get a boost in wages. Lester took all that in, gave Bane a tight little smile, said okay, and that was that. I know how this went because Lester told me all about it.

So, it’s not long before Lester is driving folks around all those acres of sagebrush and haylands, grass and gullies, answering questions about weather and wild animals and what the “natives” are like, and schools, traffic, sewerage, access roads, power drops, water rights, county zoning ordinances, stuff that a person who’s lived his whole life in our valley would be assumed to be up-to-the-minute on. Lester bluffs along best he can, actually starts getting a kick out of the job. It gives him a chance to put on a straight face and tell yarns. Okay, to be honest, he’s feeding his prospects a line of guff, and in the sales department, he’s not doing all that well.

August came along and Pauline tells Lester she’s expecting, and the very next day Bane called Lester up to the porch again, and this time invited him into the office. There’s a computer in there and a lot of gray metal cabinets and gray metal furniture. Harker’s big copy of a Charlie Russell painting of a bunch of cowhands whooping it up was missing. In its place was a picture of a cowhand standing by a pony. They’re both wearing the full outfit, wool chaps and ten gallon hat and neckerchief and pearl button shirt for the cowhand, a Navaho saddle blanket and silver-studded saddle gear for the horse. “That’s a Tony Randall,” Bane said, as if anybody’d know what a Tony Randall is. Lester nodded as if he does. Bane got down to business, which was that so far Lester had sold exactly two ranchette parcels. Bane wants Lester to spruce up his routine. “You need to put on a certain presence,” he said.

“Presence,” Lester said.

“Buyers want to know they’re investing in the genuine article. You know, Old West atmosphere, that kind of thing. I’m sure you know what I mean.”

Lester nodded again, said, “Yeah, I imagine I do.”

Bane went on, said that in the real estate area, just as in any other competitive field, the devil is in the details. What clinches a deal is the customer gets the idea that the whole thing is wrapped up neatly in one big, attractive package. Lester is still slow to catch on. He’s wondering if he’s the package, or is it the ranchette parcels? The penny drops when Bane says he wants Lester to wear a Stetson.

By this time Lester gets into his stubborn mule sulk, but then, remembering Pauline’s news, the sulk runs out of steam, doesn’t get anywhere near full bore. Hang onto the job, that’s bottom line. He tells Bane he has a fake black Stetson and it’s a good fit and he’d wear it. He gets ready to leave, but Bane has a lot of mule in him too. Remember, he’s a very rich weasel and that wasn’t handed to him on a platter, which fact he’s already mentioned two or three times. He said, “No. I’ll furnish the hat,”

I’ll throw in here that Bane was showing a blind side, never asking himself how he could expect Lester to get all fired up about selling piece by piece a big spread of land that he’d worked on and hated and gotten used to in a thousand ways. I don’t mean Lester ever gave me a big speech about this, but I know, just the same. All of us in our town and valley know. We’d seen what happened to other places and now it was our turn and a lot of us natives bitched about it. Wages low, rents high, and so on. Some of us took on these rapid-fire changes like ducks to water, made money hand over fist, but most of us couldn’t seem to get the hang of it. Count me in with the ones who didn’t, and Lester and Pauline too, even though Pauline’s from back east.

The hat came, FedEx, only five days later. Cream color, high crown, full ten gallon. Lester put it on, gave a good tug on the front brim. He tried his damnedest to feel like a new man, a man with presence.

Bane and his wife were not happy. Lester knew that. He’d heard loud talk from inside the house and he’d noticed the stiff, quick-step way Bane walked out of the house to his Subaru, paying no mind to the weather or what might be going on in the cottonwoods or the barn or the fields and borders of ditches. Audrey was the same. Lester sometimes wondered if she ever really heard the red-winged blackbirds calling from Badger creek.

And in town there was gossip. Audrey started dropping in at The Spigot where she’d become friendly with Mike Dawson from the Mobil station across the street. Mike usually takes a middle-of-the-morning break, crosses to The Spigot, has himself a leisurely single shot, then back to work. People notice Audrey timing her visits to fit Mike’s schedule. Well, so what? Mike is a father of three and a steady enough family man, and nobody’s caught sight of Audrey and Mike anyplace other than The Spigot. So, gossip switches to suspecting Audrey of gathering local color for a book she’s writing, but that one dies. The town finally comes around to the ordinary, tame conclusion that Audrey is a beautiful blonde trophy wife slowly going bats out on the old Harker place. Well, Lester already knew that.

One day Lance Liscomb from the RZ ranch pulled up to the Bane place and unloaded a sorrel mare and a bay gelding. Lester put them into the stalls he’d built. Audrey came from the house and watched, but from a distance. At the end of the day Lester went up to the house and told Audrey if she wants to go riding anytime he’d be glad to saddle a horse for her. She told him that would be nice. He asked if she’d prefer the mare or the gelding. “Oh, I don’t really know,” she said. “You decide.”

Days went by. Audrey didn’t follow up on the invite. Lester didn’t mind, he was busy getting acquainted with the horses, practicing bridling and saddling. He’d been horseback maybe eight or ten times in his whole life.

Well, one fine day in September Lester got up his nerve, saddled both horses and led them to the house. Audrey came to the door. He said, “Thought you might want to try out one of your horses.”

“Oh, you know, Lester, I don’t know why my husband bought them. To make me happy, I suppose. I’ve never been on a horse in my life. They scare me.”

“These are gentle enough,” Lester said,

Well, in the end she got up some courage and Lester helped her mount the mare and he took the gelding and they walked the horses to where Harker’s old irrigated hayland nudges up against the East Butte. They stayed there a while, let the horses nose around in the balsam root and dry grass. Then Lester showed Audrey how to neck-rein the mare to turn her back to the barn. Riding side by side past the old, empty hay sheds, Lester heard little whimpers from Audrey. He pulled up the gelding and the mare stopped. Audrey looked at Lester, as if she didn’t mind if he saw her tears. By now Lester is as twitchy as a cat at a field mouse runway and he said the first dumb thing he could think up. “Lance didn’t mention the names of your horses.”

“Do they have to have names?”

“Oh sure, even if you just call them ‘the bay’ or ‘the sorrel.'” Then he told Audrey that he and Pauline already had a naming job, a baby being due in late March, early April. “Need two names,” he said, “one for a boy, one for a girl.”

She said, “Maybe I’ll think of some, for the horses I mean.”

Lester put the gelding into a trot and the mare followed. Audrey bounced all over the saddle, but she grabbed the horn and held on for dear life. Lester drew up at the fieldstone foundation of an old house, pointed out the big cottonwood growing out of what had been a little eight-by-ten basement. “Original 120 acre homestead,” Lester said. “First piece of land Harker and Doris bought. They kept buying land when prices were low till they had themselves a nice spread.”

“Harker?”

Lester looked at her, truly surprised. “He was the man your, uh, Mr. Bane bought from.”

“I don’t know anything about that. His business affairs are his, nothing to do with me.”

Back at the barn Lester got stubborn, made Audrey unsaddle the mare, showed her how the cinch strap is wrapped around the ring. He made her take the bridle off too and learn how to put it back on, and the mare cooperated best she could. Audrey didn’t do well at any of it, but Lester, when he gets a bit in his teeth, he goes the limit. The upshot was he made her take an interest in those horses. Lester told me they must have used up at least an hour fooling around with horse gear. After that, Audrey went riding every two or three days. She’d take the mare one time, the gelding the next, getting to know them and, as she told Lester later, she was amazed at how those big beasts put up with her fumbly ways of treating them. But she got better, she was learning.

Bane had business in Denver or the coast and once, near end of September, he flew clear to New York. So, Bane’s beautiful wife and his hired man kept right on having the whole ranch pretty much to themselves.

About that same time the phone rang at home and it was Kathy. She was embarrassed, feeling she was being “too forward.” But I was happy as a meadowlark in springtime, told her I was glad she’d called and we talked up a storm. It was just great, that phone call. I began to have some really serious thoughts about Kathy and me. Well, no, to tell the truth, I’d already been having those thoughts, but they’d always come up hard against the damned unemployment thing.

Next day I landed a temp job hauling supplies and hunters to Morgan’s camp back in the Wind Rivers. Along about the first week of October I drove Morgan’s Dodge Ram down to Liscomb’s to pick up a couple pack horses. The windshield was frosted over and the heater wasn’t much help. When I stepped out of the cab, I heard the creek down in the willows jingling away under thin overnight ice, not cheerful, winter coming on. I stood there, taking the cold wind, making sure to do a good job of feeling sorry.

Lance and I hitched up the horse trailer and loaded the horses. Driving back through town, I saw Lester coming out of the post office. I stopped. Lester was wearing his big hat. I teased him about it. He took off the hat, twirled it, looked it over. “Sandy, you won’t believe this, but I’m gettin’ well acquainted with horses.”

I laughed. “Yeah, drivin’ millionaires around the country in Bane’s SUV.”

Lester corrected me, speaking sort of apologetically, about what he and Audrey had been up to. Horse stuff. And Audrey in big trouble. He told me about it. Then, first time ever, he asked me for advice.

I told him I had to get on the road to Morgan’s, hoping to pull in up there before dark. “Bad road you know.”

“Yeah, I know,” Lester said. He jammed the Stetson back on his head and looked up and down the street and damned if I didn’t get a second spell of feeling sorry, for Lester. I said. “I’ll get back to you.”

“You do that, Sandy, real soon.” He went off to his pickup.

I had a bit of trouble with the horse trailer on the road to Morgan’s — part of it was plain inattention, thinking about Kathy and me and Lester and Pauline and Audrey and the state of the economy. And why the hell had Lester taken the notion to be responsible for Bane’s wife? And when was I going to get a real job? Too many thoughts all in a jumble, which is why I let the trailer slide into a jackknife position against a lodgepole pine about a mile short of Morgan’s, dark coming on. The horses took it well. A couple hunters showed up, helped get me out of there.

I spent the night in a tent at the camp, had myself a good sleep, woke up early, sat with the cook for a while, sipping red hot coffee from a tin cup. Half the time I wasn’t paying much attention to the cook. He’s a great teller of stories, mostly about how bad things were back in the thirties, but this frosty morning huddled up against the stove my mind kept drifting back to the Harker place, the way it had been, a hay ranch. Irrigation ditches all dry now, foxtail grass moving in, but I was looking back to a different time, Lester and me and Preacher and Maury and Vern, wondering if life could ever get any better than that.

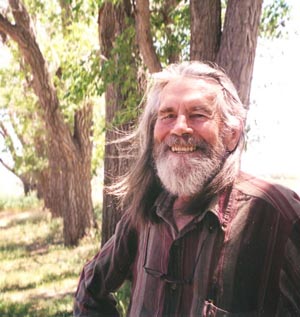

Martin Murie grew up in Jackson, Wyoming; served in the U.S. Army (infantry); studied at Reed College (BA, Literarture and Philosophy) and University of California (PhD, Zoology); taught life sciences at University of Califronia, Berkeley and Santa Barbara, and Antioch College. He retired early, to write. His novels Losing Solitude (1996) and Windswept (2001) were published by Homestead Press and Red Tree Mouse Chronicles (2000) by Packrat Books.

Martin Murie grew up in Jackson, Wyoming; served in the U.S. Army (infantry); studied at Reed College (BA, Literarture and Philosophy) and University of California (PhD, Zoology); taught life sciences at University of Califronia, Berkeley and Santa Barbara, and Antioch College. He retired early, to write. His novels Losing Solitude (1996) and Windswept (2001) were published by Homestead Press and Red Tree Mouse Chronicles (2000) by Packrat Books.