“Filipino writers in the Philippines [and the United States] have a great task ahead of them, but also a great future. The field is wide open. They should rewrite everything written about the Philippines and the Filipino people from the materialist, dialectical point of view — this being, the only [way] to understand and interpret everything Philippines.” — Carlos Bulosan1

Carlos Bulosan |

In his essay “The Writer as Worker,” Carlos Bulosan expressed the inexhaustible material that could be written on the subject of Filipinos as products of two distinct but intersecting histories (the Philippines and the United States). He stressed that this subject should always be written from a historical materialist perspective and “for the people, because the people are the creators and appreciators of culture.”2 A historical materialist orientation rejects the notion that U.S. history is comprised of unique, accidental, and unpredictable events resulting from conflicting desires in human beings. Clearly the conflict of wills has played a great role in this country’s historical development. However, what historical materialism attempts to examine is the root reasons for a clash of wills between groups of people. Karl Marx’s search for an answer to this question led him to believe that the conflicts of human beings could be explained only by a comprehensive investigation of history and the underlying driving forces of social development.3

A historical materialist orientation sees antagonisms in U.S. society as rooted in a conflict of two main classes: the capitalist class and the working class. These two classes have a completely different relationship to the production process. The working classes are the producers of wealth but do not benefit from its creation. The capitalist class controls the means of production, and therefore this small group of people are the direct beneficiaries of the wealth created. Such an approach to history is crucial to understanding Filipino migration and Filipinos’ position as an internal colony in the United States. More importantly, historical materialism is an approach that connects theory to action in the hope that people will create new beginnings. István Mészáros describes the importance of such an approach for those who are struggling against everyday situations of exploitation and oppression. He says:

Thus the emancipation of the oppressed is inconceivable without breaking and melting down the chains of this reified historical consciousness and without its positive counterpart: the reconstitution of the power of consciousness as a liberating force. This is why historical materialism must be historical. Not only in order to grasp the structures of domination in their historical genesis and contradictory development which foreshadows their dissolution, but also in order to help constitute the true historical consciousness of the new social agency.4

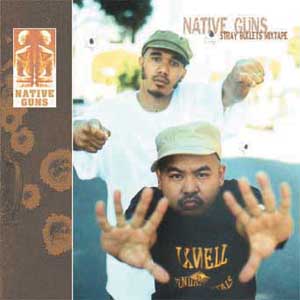

This essay is my attempt to write about Filipino American hip-hop from a historical materialist perspective with the deeper understanding that hip-hop is an art form that was created “for the people.” I begin with an analysis of hip-hop and its absorption into a culture of capitalism. I argue that its absorption has not occurred in a vacuum but is actually related to a larger weakness of U.S. society and the progressive left. Second, I claim that, for Filipino American hip-hop to effectively resist its co-optation, it must revive the anticapitalist and antiracist perspectives embodied in the cultural work Carlos Bulosan. Lastly, I look at Filipino American hip-hop artists Native Guns as a timely case study. I show that their music continues the long history of Filipinos in America who use their cultural work to resist and challenge structures of exploitation, domination, and an ideology of racism.

The glory days of hip-hop were during the 1980s, when working-class communities of color were devastated by the Reagan administration’s “trickle-down” policies that abetted police brutality and racial profiling. Artists such as KRS-One, Public Enemy, even gangster rappers like N.W.A (Niggas with Attitudes) were creating tracks that portrayed realities of Reaganism such as the phenomenon of youth moving from overcrowded and under-funded schools to overcrowded and well-funded prisons. In only two decades, however, hip-hop music proliferated from neighborhood rock parties in the South Bronx and boom boxes of South Central Los Angeles to the white suburban homes throughout the country. Today, hip-hop is a billion-dollar industry with growing global influence. The corporate music industry has been incredibly adept at redirecting hip-hop’s social energies away from a common language of work, suffering, and protest towards messages of financial success and materialism. As a result, numerous hip-hop artists have shed their working-class background for extravagant cars, flashy jewelry, and stylish clothes. The music that dominates the top of the charts speaks to this shift, as icons such as Jay-Z, 50 Cent, and Lil’ Kim commonly describe themselves as business entrepreneurs, thereby associating themselves more closely with the white male business giants than with the people from their respective working-class communities of color.

Hip-hop’s absorption into a culture of capitalism is not an isolated occurrence but replicates the experience of many movements of the progressive left. The resurgence of neoconservatism, the decline of national-liberation struggles in the Third World, and the collapse of the Soviet Union have had a demoralizing effect on progressive movements throughout the United States, thereby instilling doubt that collective action can bring about social change. Barbara Epstein’s diagnosis of weakness in the women’s movement over recent decades — “widespread acceptance of the view that there is no alternative to capitalism”5 — is clearly applicable to analysis of hip-hop as well as larger society.

Hip-hop still remains a valuable musical form that can raise people’s consciousness of racism in this society, however. Mainstream artists such as Ice Cube, Queen Latifah, and Jay-Z have produced songs that call attention to black-on-black crime and police brutality in America’s inner cities. Furthermore, their music is an example that shows how the privileging of class over race is not the most constructive way to describe circumstances of domination and exploitation in the U.S. metropolis. David Roediger in his important book The Wages of Whiteness describes racism as “a large, low-hanging branch of a tree that is rooted in class relations.” He elaborates that “we must constantly remind ourselves that the branch is not the same as the roots, that people may more often bump into the branch than the roots, and that the best way to shake the roots may at times be by grabbing the branch.”6 Given the recent disaster that demolished New Orleans and the inability of government bodies to mobilize adequate resources to the people hit hardest by this catastrophe, it is more precise to describe race as the piercing blade and class relations as the spear.7 Differently located, but connected nonetheless. Without analyzing race and class as dialectically linked in the reproduction of capitalist relations, we are ill equipped to suture the deep cut that has afflicted so many people in New Orleans, Los Angeles, and other cities throughout the country.

A racial hierarchy was formed in the United States by assigning economic and psychological privileges to whites and naturalizing them. According to Roediger, Europeans did not arrive at the United States as “whites” — they arrived as Irish, Germans, and Italians. Through the construction of whiteness and incorporation of various European immigrants into it, the dominant class divided the masses, prevented unity, and concealed the roots of exploitation. The ideology of racism has changed significantly from the formative years of working-class racism during the 19th century that Roediger astutely describes. The ideology of the new racism recognizes race as a social construction, superficially celebrating cultural, national, and ethnic forms of “difference” . . . only to justify and maintain racial and class privileges. As Peter McLaren notes in Teaching against Capitalism and the New Imperialism, “the regulating discourse [of race] becomes, You can be different but on our terms (that is, those set by the white ruling class). If you follow our ground rules, we will celebrate your difference. If you don’t, then you can suffer the consequences.”8

Examining the diverse historical forms of racism, a fluid ideology to preserve dominant class interests and to divide the working class, is crucial to understanding the history of Filipinos in the United States. Bob Wing, in “Crossing Race and Nationality,” reminds us that, during the 1960s, the Asian-American movements “dramatically transformed the political consciousness and institutional infrastructure of the different Asian-American communities.”9 Among Filipino Americans, a critical consciousness of and opposition to alienation and racial oppression emerged decades earlier. Omitted from the psyche of Filipino Americans by schools, the media, and other state apparatuses, however, is the critical understanding that there is a deep tradition of resistance that unites Filipino cultural work with activism. Reconnecting to this history and linking the common struggles and inspirations of Filipino immigrants during the “golden years” of U.S. capitalism (1945-1973) won’t lead to a revival of the more radical movements witnessed in the 1960s. However, if hip-hop and youth can revitalize the spirit personified in the work of Carlos Bulosan, stronger and more effective strategies to counter the logic of capital can materialize.

Once asked by a reporter “‘What is?’ Marx replied without hesitation, ‘Struggle’.”10 That only by struggle does one obtain a critical consciousness is clearly expressed in the experiences and writings of Filipino writer Carlos Bulosan. Bulosan was born in the Philippines on November 24, 1913. Like many Filipinos who were driven out by poverty in the Philippines as a result of U.S. imperialism, he traveled to this country in pursuit of the “American dream.” He arrived in Seattle, Washington during the Great Depression — in the summer of 1930 — at the age of seventeen. In the same year, there were 108,260 Filipinos in this country working mostly as farm workers on the West Coast. These new Filipino immigrants were considered neither “citizens” nor “aliens,” resulting in their subjugation to various forms of racist discrimination such as exclusion from working in government and owning land and extreme forms of violence.11 Five years after Bulosan’s arrival, the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1935 was passed, changing the Philippines’ status to “commonwealth,” promising eventual independence of the islands in 1946, and at the same time cutting Filipino migration to the U.S. to fifty persons per year.12 In the wake of the Tydings-McDuffie legislation, President Roosevelt signed the “Repatriation Act,” which offered free transportation for Filipinos back to their homeland. “But Filipinos who took advantage of the offer could not again re-enter, so in effect, the Repatriation Act was a deportation act.”13 The white working class supported the deportation of Filipinos to maintain their economic and psychological privileges.

The forced competition experienced between Filipino and white working classes for limited resources is an intrinsic component of capitalism. Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy argue in Monopoly Capital that no reforms can get to the root of anti-immigration and racist sentiment in this country without addressing the current economic system. They state that, in the past, “entire groups could rise because expansion made room above and there were others ready to take their place at the bottom.” What Bulosan and the thousands of Filipinos experienced was that the ascent to the higher rungs of the economic and social ladder was no longer possible for entire groups of people — only individuals. Baran and Sweezy claim, “for the many nothing short of a complete change in the system — the abolition of both poles (power at one end and powerlessness at the other) and the substitution of a society in which wealth and power are shared by all — can transform their condition.”14

Bulosan remained in the United States at first laboring in the fields and canneries of the West Coast and later involved himself with the more radical union organizations that linked imperialism abroad with racism at home. Such unions included the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA) and the Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO). These unions were eventually targeted as communist groups in McCarthy’s pursuit of those deemed anti-patriotic during the 1950s. Bill Fletcher — in his essay “Can U.S. Workers Embrace Anti-Imperialism?” — says the operative definition of “anti-patriotic” at the height of the Cold War was actions that stand in direct opposition to the U.S. imperial interests at home and abroad. Fletcher further asserts that, for government authorities, antiracist activity at home were clear signs of “anti-patriotic” communist activity by that definition. He describes how “unions representing over one million workers were expelled from the CIO for failing to sign affidavits . . . signifying that their leaders were not communists.” Evidently, the members who were expelled from the CIO were those that “had the strongest positions against racism within the labor movement.”15

From 1936-1938, Bulosan was confined to the hospital for tuberculosis and kidney problems. During this time, he read voraciously at the rate of a book a day.16 This process of reading from the work of such authors as Karl Marx, Pablo Neruda, John Steinbeck, Maxim Gorki, and Jose Rizal in accord with his experiences as a laborer and organizer congealed his revolutionary praxis. Through critical reflection, he entered into the process of writing for recuperating the past, questioning the present, and imagining the future. Bulosan wrote about the underside of America for those entrapped in conditions of racist violence, hunger, and impoverishment. He described his duty as an artist and writer as an effort to “trace the origins of the disease that was festering American life.”17 While examining the disease, he articulated the desires that burned in the hearts of the dispossessed who were struggling to create more democratic and just societies not only for Filipinos in the U.S. but also throughout the world. He writes:

What impelled me to write? The answer is — my grand dream of equality among men and freedom for all. To give a literate voice to the voiceless one hundred thousand Filipinos in the United States, Hawaii, and Alaska. Above all and ultimately, to translate the desires and aspirations of the whole Filipino people in the Philippines and abroad in terms relevant to contemporary history. Yes, I have taken unto myself this sole responsibility.18

In his writings, Bulosan renders class visible not as a differentiated position or as a naturalized stratification but as a process, an experience, and a relation. In his essay, Freedom from Want he writes:

But we are not really free unless we use what we produce. So long as the fruit of our labor is denied us, so long will want manifest itself in a world of slaves. . . . If you want to know what we are, look upon the farms or upon the hard pavements of the city. . . . We are the creators of abundance.19

For Carlos Bulosan, it is impossible to speak of production without connecting it to surplus value that is extracted from the worker. His words resonate today for those who share a lived experience of production that is marked by exploitation and conflict. In a country of great wealth and opulence, he dialectally connected the prosperity of the small few to those who “are bleeding where clubs are smashing heads, where bayonets are gleaming. . . . Where the bullet is crashing upon armorless citizens, where the tear gas is choking unprotected children. Where the prisoner is beaten to confess a crime he did not commit. Where the honest man is hanged because he told the truth.”20

Ellen Meiskins Wood, in Democracy Against Capitalism, locates the antagonisms that Bulosan portrayed in his literature in class conflict. She states, “class as a relationship and process stresses that objective relations to the means of production are significant because they establish antagonisms and generate conflicts and struggles; that these conflicts and struggles shape social experience.” She goes on to explain, “over time we can discern how these relationships impose their logic, their pattern, on social processes.”21 Bulosan expresses this point with eloquence, “Thus, if the writer has any significance, [s]he should write about the world in which [s]he lives: interpret his [her] time and envision the future through his [her] knowledge of historical reality.”22 Hip-hop needs to take note.

Historically, the oral expression central to hip-hop reflected the youth of color who were struggling to survive in a system that continually justified the injustice that surrounded them. Hip-hop as an art form originated from the youth of inner city New York who were making sense of a history of contradiction that was not of their choosing. For hip-hop to uphold its history of resistance and assist in an emancipatory struggle, it will need to rise above glorifying “thug life” or, in the words of Bulosan, “adding form to decay.” Instead, hip-hop must expose the origins of people’s hunger and deprivation, in the hope that people will take part in the struggle to attain “a higher dream of human perfection.”23

The Filipino American rap group Native Guns is an important case study for hip-hop. Emees Kiwi and Bambu grew up in Southern California, highly influenced by the gangster rap that originated in their communities. Bambu discusses the influence of gangster rap — how it helped him come to grips with the experiences he faced in his community such as police harassment, drugs, and a lack of academic or job opportunities. He states, “Our music is just a continuation of a story started by gangster rap. I’m strongly influenced by [that] music and have learned and progressed from it.”24 While hip-hop originated from the experiences of African Americans, according to Victor Wallis, “hip hop authenticity is rooted not in anyone’s physical traits or language, but in the shared experience of oppression.”25 Native Guns’ music demonstrates how Filipino-Americans are making use of hip-hop to articulate the contradictions of capitalism they experience. Their work continues in the tradition of Carlos Bulosan as they express a clear understanding that they are products of a specific history marked by struggle and resistance. Acknowledging this history, Kiwi states, “We come from a long tradition of . . . artists who have challenged the status quo and mainstream thinking,” and he elaborates that “our voice comes from a Filipino American perspective, giving us some distinct experiences to rap about.”26 As a result, their music takes cultural action against the ruling elite while addressing the social conditions that have left their communities devastated.

Click here to listen to Track 17 of Stray Bullets by Native Guns! |

Prior to the tragic events that took place in Washington D.C. and New York City on September 11, 2001, the U.S. government controlled the challenge of immigration with a concealed logic of racism (recall Propositions 21, 209, and 227 in California). Anti-immigration policies were anchored in the assumed tax burden of immigrants as well as their supposed propensity for criminality. However, with the shallow sentiment of pluralism celebrated in the United States, borders were still represented as open for immigrants who were willing to work hard and sacrifice to attain the “American Dream.” Native Guns expresses the realities for immigrants in the United Sates prior to 9/11 in track 17 of their latest CD, Stray Bullets Mix Tape Volume 1. They sing,

All my illegal aliens, black or Mexican

Whether banana boat or hole in the fence

I’m down with ya, come across that border, get rich.

But first let me tell you about the land of opportunity,

The ones who run the country look nothing like you and me,

So they patrol the community, cage us into poverty,

Feed you television so you’ll know that you’re an anomaly,

That means you’re different,

Good luck trying to pay the rent,

And welfare, well yeah, it really does exist,

But you’ll be on that shit for good,

Cuz, in the hood, you’ll have to work a few jobs

So that your kids eat like they should,

And the junk food epidemic keeps your kids unhealthy

To die at thirty-five and leave the world unwealthy.

So that’s the Promised Land you left your country for

But it’s the same, it’s corrupt, and you still poor.27

The realities of immigrants have only worsened in a post 9/11 world. The U.S. government has been given the “green light for a full blown and bipartisan agenda of repression at home, as well as for the expanded imperial project abroad.”28 Reminiscent of McCarthyism in the 1950s, the U.S. is again on a crusade — this time, to hunt anti-patriotic, domestic terrorists. The reactionary legislative agenda did not end with the Patriot and Homeland Security Acts that have institutionalized racist policing of all immigrants deemed unassimilable. On December 16, 2006, the United States House of Representatives passed H.R. 4437 titled “The Border Protection, Antiterrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005.”29 If passed by the United States Senate, President Bush could sign a bill that equates illegal immigrants with terrorists. Undocumented immigrants as well as any individual or organization that “harbor” them could be charged with criminal penalties and subject to incarceration. Furthermore, if this bill passes, a 700-mile fence will be constructed along the Mexico border to deny access into the United States.30

The subjugation immigrants face in the “belly of the beast” is connected to the outright repression in the Third World: to take just two examples, in the Philippines, commonly referred to as the “second front” in the “war on terrorism,” students, activists, and politicians are continual targets by military death squads supported by the U.S. government, and in Iraq, we will probably never know the number of civilians killed by U.S. “smart bombs.” The common denominator is what Lenin acknowledged as the evolution of capitalist development in all its complexity (military, political, social, and economic). Peter McLaren identifies inseparable dominations at home and abroad as the new imperialism “connected to the increased competition for control over global territories (raw materials and resources) between imperialist rivals such as the United States, Britain, and France; the coming of age of ‘new mammoth’ corporations that seek competitive advantage through their own home-based nation-states; and the development of an entire world system of colonization that creates uneven development and economic dependencies.”31 However, it is important to remember that, whenever such a system of subjugation exists, there are always resistance to it, voiced in thunders as well as whispers. In the same song, Native Guns unites the resistance found worldwide:

Free Palestine, Iraq and all victims of occupation,

Every human got to fight for their self-determination.

By any means necessary, pencil or pistol,

Beats and lyrics being played at the disco

They label us criminals cuz we got guns,

We got guns cuz we got no other options.

Guerilla armies up in Third World jungles,

To gangs in the hood, it’s all the same struggle.32

The struggles for self-determination in the Philippines, Palestine, Iraq, and the United States are not necessarily all based on the praxis of anti-capitalism, anti-racism, or anti-imperialism. However, Native Guns rightfully grounds the sentiment for justice, dignity, and social transformation in the experience of love, echoing Che Guevara’s description of revolutionary praxis that he describes as “guided by strong feelings of love,” without which “it is impossible to think of an authentic revolutionary without this quality.”33 Allow me to conclude with the lyrics of Native Guns that reproduce Che’s conviction:

We want freedom,

We want something to be proud of.

When it comes down to it,

Revolution’s all about love.

The kind of love that one would give up their life for,

So that their family won’t ever have to die poor.34

1 San Juan, Epifanio. On Becoming Filipino: Selected Writings of Carlos Bulosan. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1995, pg. 144.

2 Ibid.

3 Selsam, Howard and Martel, Harry. Reader in Marxist Philosophy: From the Writings of Marx, Engels, and Lenin. International Publishers Co., Inc., 1971, pg. 183.

4 Constantino, Renato. Neocolonial Identity and Counter-Consciousness: Essays on Cultural Decolonization. Merlin Press, New York, 1978, quoted from introduction written by Mészáros, pg. 3.

5 Epstein, Barbara. “What Happened to the Women’s Movement?” Monthly Review 53.1, May 2001.

6 Roediger David R. The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class. Verso, New York and London, 1993, pg. 8.

7 I didn’t come up with this analogy on my own. It comes from lecture notes in John B. Foster‘s Sociology Social Theory II at the University of Oregon on February 21, 2006.

8 McLaren, Peter and Farahmandpur, Ramin. Teaching Against Global Capitalism and the New Imperialism: A Critical Pedagogy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2005, pg. 133.

9 Wing, Bob. “Crossing Race and Nationality: The Racial Formation of Asian Americans, 1852-1965,” Monthly Review 57.7, December 2005, pg. 14.

10 McLaren, Peter. Che Guevara, Paulo Freire, and the Pedagogy of Revolution. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., New York, 2000, pg. 194.

11 San Juan, op. cit., pg. 4.

12 Wing, Bob. “Crossing Race and Nationality: The Racial Formation of Asian Americans, 1852-1965,” Monthly Review 57.7, December 2005.

13 Bulosan, Carlos. America is in the Heart. University of Washington Press, Seattle, quoted in introduction written by Carey McWilliams pg. xiv.

14 Baran, Paul and Sweezy, Paul. Monopoly Capital: An Essay on the American Economic and Social Order. Monthly Review Press, New York, pg. 279.

15 Foster, John and McChesney, Robert (editors). Pox Americana: Exposing the American Empire. Monthly Reivew Press, New York, 2004, pg. 123.

16 Bulosan, op. cit., quoted in introduction written by Carey McWilliams pg. xvii.

17 San Juan, op. cit., pg. 126.

18 Cabusao, Jeffrey Arellano. “Some Notes for Reconsidering Carlos Bulosan’s Third World Literary Radicalism,” Our Own Voice, March 2006.

19 San Juan, op. cit., pg. 131.

20 San Juan, op. cit., pg. 133.

21 Wood, Ellen Meiksins. Democracy Against Capitalism: Renewing Historical Materialism. Cambridge University Press, 1995, pg. 82.

22 San Juan, op. cit., pg. 143.

23 Carlos Bulosan quoted in: San Juan, Epifanio. Reading the West/Writing the East: Studies in Comparative Literature and Culture. Peter Lang Press, San Francisco, 1992, pg. 150.

25 Wallis, Victor. “Introduction,” Socialism and Democracy 18.2.

27 Native Guns from their album, Stray Bullets MixTape Vol 1.

28 Foster and McChesney, op. cit., pg. 156.

30 Summary points taken from www.justiceforimmigrants.org.

31 McLaren and Farahmandpur, op. cit., pg. 237.

32 Native Guns, op. cit.

33 McLaren, op. cit, pg. 77.

34 Native Guns, op. cit.

Michael Viola is a graduate student at the University of Oregon with research interests in education, race studies, imperialism, and the Philippines. He is the west coast director and one of the co-founders of Sandiwa, a national Filipino American youth organization. You can contact him at [email protected].