South of the Border

The residents of the colonias of Matamoros, Mexico are refugees of the modern free trade wars. Located near the maquiladora factories south of the US-Mexico border in the lower Rio Grande Valley, the impoverished colonias provide sharp contrast to the affluent suburbs and bustling shopping malls just across the river in Brownsville, Texas.

Like refugee camps throughout the world, the Matamoros colonias are situated on wastelands unfit for human habitation — one the site of a former municipal garbage dump, another in an area liberally contaminated by toxic waste.

Amazingly, grassroots colonia associations somehow manage to supply meager utilities and social services. Electric power “borrowed” from municipal sources located several miles away is imported through jerry-rigged drop lines, and solid waste is exported at least to the margin of the settlement.

In the “plaza” of many of the colonias, one finds a simple building, usually decorated with a native mural, which serves as city hall, medical clinic, primary and secondary school, adult education center, and, during fiestas, a cafeteria. The dirt “plaza” itself is a social center, political forum, and playground for the children of the community.

The residents of the colonias, mostly migrants from the southern states of Mexico, provide the workforce for the 147 maquilas that operate in Matamoros, manufacturing products for export, mostly to the US. The current count for the state of Tamualipas, which includes Matamoros, stands at 312 maquilas and includes such industrial giants as Black and Decker, Caterpillar, Delphi Delco, Maytag, Panasonic, Sony, Sunbeam, and TRW. These multinationals, which employ thousands of workers who live in the colonias, are installed in immaculate facilities, subsidized and in some cases developed by the Mexican government. The contrast between workplace and home is arresting.

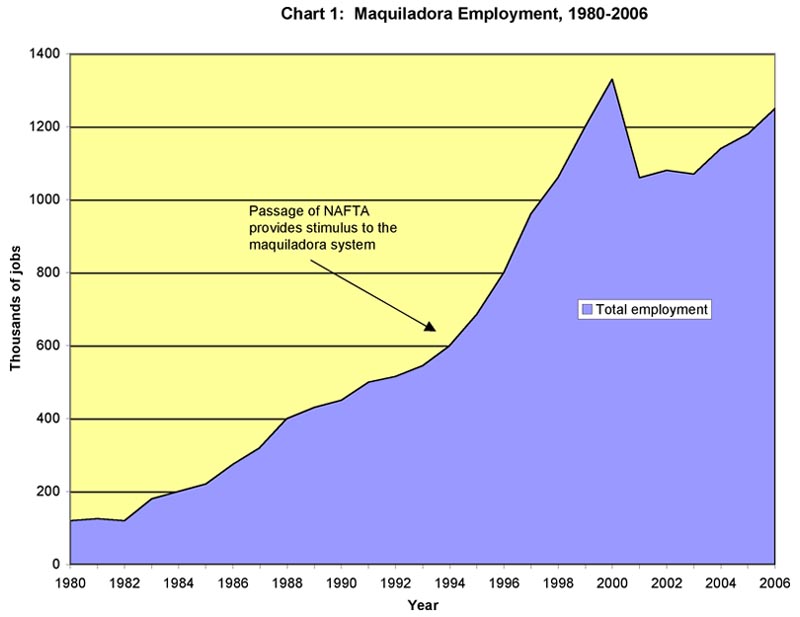

Offshoring jobs to maquiladoras has been a singularly successful venture for foreign firms. This success is reflected in Chart 1 that records the growth of the maquila industry in Mexico:

Download the chart as Excel file.

Chart 1 shows that maquiladora employment increased steadily during the 1980s and then boomed after the passage of NAFTA, a treaty that opened all of Mexico to exploitation by foreign firms. The system peaked in the year 2000 with 1.3 million workers employed in over 3,000 plants. Employment dipped in 2001 because of the recession in the US but is currently undergoing a strong recovery.

Overall, the maquiladora system has been a boon to foreign capitalists, especially US industries, keeping the costs of production down and profits up in many critical industries. The ultimate cost of the system is falling on the Mexican people and their environment — labor abuse is rampant and environmental destruction continues. These two rudiments of global free trade literally come together in the colonias.

The canal at Colonia Benito Juárez |

This photo, taken from the bank of a canal that runs next to the Colonia Benito Juárez in Matamoros, clearly shows a cascade of solid waste from the settlement merging with a crust of chemical waste on the water’s edge that comes from upstream maquilas.

The Coalition for Justice in the Maquiladoras (CJM) stands tall for the workers in the middle of this mix of environmental destruction and labor exploitation.

A battle standard of the CJM. The message to the boss is “You will raise wages in the maquila!”)

Listening to the CJM

The CJM, a grassroots international organization, has been fighting for the rights of workers in the maquiladoras for 17 years. Originally based in Mexico, the US, and Canada, the organization is expanding its reach into Central America and the Caribbean to counter the multinationals that are bent on ensnaring the entire world in their web of free trade. Both the successes and failures of the CJM offer valuable lessons for activists in the North. These lessons were offered up freely in the recent international forum on free trade, labor, and migration, Bring Down the Wall: We Are All Migrants! hosted by the CJM in Matamoros at their annual meeting (November 3-5).

Lesson #1: Only real democracy can produce political consensus.

As an observer from the North, I was initially put off by the lack of formal structure of the assembly. Everyone involved in CJM is allowed to have his or her say, no mater how long it takes, and consequently it took a long time to arrive at a vote. When I asked Judy Ancel, the president of CJM, about this, she told me that the Latin American brothers and sisters consider parliamentary procedure a tool to control the voice of the people and will not tolerate it.

But proof is always in the practice, and my initial skepticism disappeared when I saw the authentic political consensus forged in the assembly. The terms “brother” and “sister” mean family in both a political and a palpable sense. “Of the people, by the people, and for the people,” a slogan in the North, is political practice in the CJM.

President Judy Ancel and maquila workers share the floor at the CJM convention.

President Judy Ancel and maquila workers share the floor at the CJM convention.

A most remarkable feature of CJM democracy is its commitment to the rights of women who make up a majority of maquila workers — a commitment clearly articulated in the organization’s mission statement:

“To defend the rights of women workers, guaranteeing access to employment without discrimination, health, reproductive health, equity in the workplace, and equality in all aspects of life.”

This objective, exemplary by any standards, is mirrored in the composition of all levels of the organization. Martha Ojeda, the Executive Director, is a dynamic woman who embodies the spirit of participatory democracy that animates the CJM.

Lesson #2: Successful political struggle must be grounded in the concrete.

Workers from the maquiladoras are involved at every level in CJM and their experiences form the basis for the organization’s structure, policy decisions, and organizing activities. The experiences of sisters and brothers from Canada to southern Mexico and the Dominican Republic were presented, discussed, and summarized in small groups and then submitted for consideration to the assembly at large. Though everyone had his or her say, the voices of maquila workers and colonia activists dominated the forum.

Lesson #3: Successful labor struggles must be linked to community issues.

The link between terms of employment in maquilas and living conditions in the colonias lies at the heart of CJM. The concept of justice in the organization applies equally to economic justice for workers on the job and social justice for workers and their families in their communities.

Illustrating this organizational commitment to worker communities, the entire CJM assembly went to the ColoniaFuerza y Unidad (Strength and Unity Colonia) to meet and share supper with the residents there. Hosted by the colonia, it was a festive celebration of unity with good food and lively music, illuminated by throngs of children who tossed fluorescent toys high into the night sky.

Lesson #4: Grassroots labor/community movements are strengthened by domestic solidarity.

This lesson was illustrated when the CJM assembly passed a resolution condemning the Mexican government’s violence against the ongoing teachers’ strike in Oaxaca and then temporarily adjourned the meeting in order to conduct a solidarity demonstration at the international bridge. Despite a hostile reception by US Border Patrol agents, the CJM demonstrators, who were joined by many Mexican pedestrians, spent time on the bridge engaging in lively dialogue with passing motorists.

CJM solidarity demonstrators, banners and posters in hand, board the bus bound for the international bridge.

At the international bridge. The banner calls for an immediate end to the conflict in Oaxaca.

The assembly returned to its work immediately after the demonstration without missing a beat. The event was well reported in the local Mexican press the following day.

Lesson #5: The ultimate success of grassroots labor/community struggles in the modern world is tied to strong international links.

This is testified to by the practice of the CJM — their most successful campaigns in the maquilas have been reinforced by coordinated actions against the foreign firms in their home countries. This penultimate political lesson was reflected in the proposal that was passed at the assembly to change the language in the CJM constitution and by-laws from “tri-lateral” (Mexico-US-Canada) to “international” in order to reflect the expanding arena of struggle as the architects of free trade widen the scope of their targets.

The international links of the CJM were strengthened at the assembly by simultaneous translations delivered by world-class interpreters.

World-class interpreters communicated both the words and spirit of the assembly.

The most important lesson that I learned at the political forum hosted by CJM in Matamoros is that we in the North are going to have to run to catch up with our sisters and brothers south of the border if we want to be involved in shaping the future.

This girl, growing up in Colonia Benito Juárez,

is part of that future.

(CJM is based in San Antonio, Texas. More information about their mission and activities can be found at www.coalitionforjustice.net.)

Richard D. Vogel is an independent socialist writer. He has recently completed a book, Stolen Birthright: The U.S. Conquest and Exploitation of the Mexican People.

|

| Print