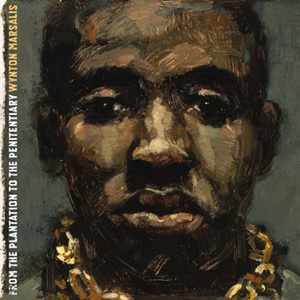

I’ve been listening to Wynton Marsalis’ new disc From the Plantation to the Penitentiary a lot. It’s got the music — a neat jazz combo running through a variety of styles. It’s just enough bop and bebop so it doesn’t put one to sleep like a Kenny G. solo, but it’s not an avalanche of sound like those from Coltrane’s thundering Ascension either. Then there’s the vocals. Yes, the vocals. Mr. Marsalis is putting some lyrics to his tunes on this one, and he’s got plenty to say. The first discs I thought of after listening to the first tune were Rahsaan Roland Kirk‘s early 1970s works Volunteered Slavery and Blacknuss. That eponymous tune, “From the Plantation to the Penitentiary,” is an angry history of the black man in the United States. Brought over in chains, emancipated, and back in chains. It’s intentional, make no doubt about it.

I’ve been listening to Wynton Marsalis’ new disc From the Plantation to the Penitentiary a lot. It’s got the music — a neat jazz combo running through a variety of styles. It’s just enough bop and bebop so it doesn’t put one to sleep like a Kenny G. solo, but it’s not an avalanche of sound like those from Coltrane’s thundering Ascension either. Then there’s the vocals. Yes, the vocals. Mr. Marsalis is putting some lyrics to his tunes on this one, and he’s got plenty to say. The first discs I thought of after listening to the first tune were Rahsaan Roland Kirk‘s early 1970s works Volunteered Slavery and Blacknuss. That eponymous tune, “From the Plantation to the Penitentiary,” is an angry history of the black man in the United States. Brought over in chains, emancipated, and back in chains. It’s intentional, make no doubt about it.

Piano melodies and bass lines from the earth. Lyrics channeling Langston Hughes in meter and intent. Diatribes against the emptiness of consumer culture whether it be car sales or gangsta rap. The tune “Love and Broken Hearts” wonders, like the best of Donny Hathaway: where is the love? Let’s start at the beginning and wander around the tunes Marsalis has laid down here. From the Plantation to the Penitentiary is at times a soulful moan. Other times it sparkles with a hope implicit in Wynton’s horn. That trumpet is the voice of the men in Angola or Partchman Farm. It’s the women picking cotton across America’s South. The lyrics tie the servitude all together. Jennifer Sanon’s vocals are an instrument of their own. Oppression on the plantation and the chains of the inmate gangs. The money involved that made the United States the capitalist country that it is and the multibillion-dollar prison industry that replaces the plantation for way too many black men in this land.

Speaking of capitalism, that’s what this disc is about. Everything is for sale. “Gimme this, Gimme that. . . . I got to have. I got to have now.” Those are lines from the tune called “Supercapitalism.” It’s the conditioning we’ve been provided. The ultimate consumer consciousness is but one lament. The fact that the people’s history is erased, or renamed and sold as lies, is another. The loss of love and its replacement by violence and hookup sex is another. No belief in the future and no care for one’s neighbors. It’s a pretty bleak picture Mr. Marsalis and his combo are painting here. Shattered people without a home, left to suck on capitalism’s bone. And where are the organizers? The leaders who would show us a way out of this tragic existence? That’s the question Wynton asks in the final tune in this layout, “Where Y’all At?” We believe they are out there, but when will they step up? Maybe then, things aren’t so bleak. Perhaps this disc is actually a call to change, not a poem of despair.

Musically, again. It’s not adventurous like the aforementioned Rahsaan Roland Kirk disc, but it’s an enjoyable blend of styles and tones. Rhythmically, it goes from foot tapping to danceable to contemplative. Wynton Marsalis is a traditionalist, yet he goes outside his realm here, and it works. There’s a series Marsalis did that I saw on PBS where he talked about jazz — its history, its musical structure, and its cultural meaning. The series was enjoyable and informative without being pedantic. This disc is like that, except it’s all music. The words here are songs, not introductions to songs. The singer brings the words into the forefront of the combo without taking the spotlight away from the message. Like Hermes, she delivers the words without becoming the story. She is Calliope to the combo’s Orpheus. The combo includes Marsalis on trumpet, Walter Blanding on tenor & soprano saxophones, Dan Mimmer on piano, Carlos Henriquez on bass, and Ali Jackson, Jr on drums. All four sidemen are relatively new names on the scene and should be proud of their involvement here. I hope they go on tour with it. Such an endeavor might encourage them to stretch these songs out a little more.

In his liner notes, legendary jazz critic Stanley Crouch notes that “art evolves with society and is informed by society.” I would take that a step further and say that the best art can also influence the direction a society can take. My next logical statement is that this disc is some of the best art I’ve heard in a while, especially from the jazz world. From the Plantation to the Penitentiary is a reflection of the bankrupt society of greed and racism that we live in as much as it is a lesson in jazz and other American music forms. The history and frustration expressed in the lyrics illustrate the evolution of the African-Americans oppression in terms of the facts on the ground (and hanging from the trees) and the particular psychology of the market and its racial history. Yet, it’s not only about black Americans. It’s also about the rest of us, too. The racist history we all share, which formed our economic system, is enveloping us all in its battle to control. Mr. Marsalis’ most recent effort can become part of that rarest echelon in art: it is good enough to influence our direction if only enough listen.

(By the way, the line “The land that never has been yet,” in the title is from Langston Hughes poem “Let America Be America Again.”)

Ron Jacobs is author of The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground, just republished by Verso. Jacobs’ essay on Big Bill Broonzy is featured in CounterPunch‘s new collection on music, art and sex: Serpents in the Garden. He can be reached at <[email protected]>.

|

| Print