|

“O there are times, we must confess To harboring a whim — we Like to picture old Karl Marx Sliding down our chimney” — Susie Day “Help fund the good fight. By contributing to MR, you help reinforce the left and reclaim the future.” — Richard D. Vogel To donate by credit card on the phone, call toll-free: You can also donate by clicking on the PayPal logo below: If you would rather donate via check, please make it out to the Monthly Review Foundation and mail it to:

Donations are tax deductible. Thank you! |

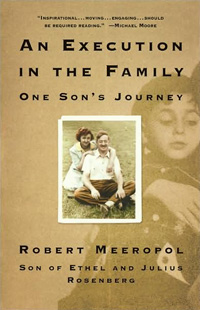

AN EXECUTION IN THE FAMILY by Robert Meeropol BUY THIS BOOK |

Half a century has passed since the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg on June 19, 1953. For those coming of age in the new millennium, the Rosenbergs’ story (if they know it at all) must seem as remote as the story of Sacco and Vanzetti did to their parents’ generation. Yet the case of “the atomic spies” still has the capacity to provoke anger, bitterness, and even fury.

Robert Meeropol, the Rosenbergs’ younger son, was only six when his parents were put to death at Sing Sing. He remembers nothing of his family’s working-class apartment in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. He has, he says, even forgotten the sound of his parents’ voices. Yet the cruelty done to his parents (whom he never publicly acknowledged until he was 25) was unquestionably the most traumatic event of his life.

That Julius Rosenberg was a Soviet spy now seems beyond question. But the espionage he engaged in, with the aid of Ethel’s brother David Greenglass, had nothing to do with atomic secrets. The Venona decrypts (of KGB transmissions in 1944 and 1945) show that Julius only passed non-atomic military information — including a proximity fuse for anti-aircraft weapons — to our Soviet allies, who were then locked in a life-and-death struggle with the Nazis. His solidarity with our allies does not excuse his crime, but — since 25 million Soviet citizens died fighting the Nazis — it certainly extenuates it.

The Rosenbergs were arrested and charged with conspiracy to commit espionage in 1950. Conspiracy, as Judge Learned Hand said, is “the darling of the prosecutor’s nursery,” and a much easier crime to prove than espionage or treason. But the Rosenbergs’ conviction ultimately hinged on judicial misconduct and the perjured testimony of the prosecution’s key witness.

Judge Irving Kaufman’s desire to see the Rosenbergs convicted was embarrassingly transparent. He colluded with the prosecutors, even discussing sentencing options before the verdict was rendered. He castigated the Rosenbergs in open court, blaming them for the deaths of “our boys” in Korea.

But Kaufman’s egregious behavior paled before David Greenglass’s betrayal of his sister and brother-in-law. It didn’t take much to make Greenglass squeal: promised leniency by the prosecution, he lied under oath. In a 2001 video documentary, he confessed that the FBI coached him to give false testimony. Among other whoppers, he told the court that Ethel had typed notes of their “atomic” espionage. This testimony almost certainly sent his sister to the Death House. “I don’t know who typed the notes,” Greenglass told his interviewers, “and to this day I can’t remember that the typing took place.” Greenglass got fifteen years and was released in ten; Ethel got six surges of 2,000 volts each. For Meeropol, merely hearing his uncle’s name is “like taking a bath in sewage.”

Meeropol’s engaging memoir An Execution in the Family begins where his parents’ story ends. He was sent outside to play ball the night his parents were electrocuted. With his brother Michael, he was eventually adopted by Anne and Abel Meeropol, Old Leftists in whose lively and often raucous home he passed his childhood. But the nightmare of his parents’ killing made him wary of intimacy. He never cried as a child, he says, and the woman who became his wife threatened to abandon their marriage because of its “emotional poverty.”

In his twenties Meeropol became a lawyer, a defender of left-wing causes. But it wasn’t until his 43rd year that he found his true vocation. Disillusioned with lawyering, he founded the Rosenberg Fund for Children, which gives aid to children of imprisoned, exiled, and persecuted activists. Under his leadership, the RFC has dispensed $2.5 million in assistance ranging from therapy to summer camps to educational grants. The vengeful fantasies that Meeropol once entertained have given way to what he calls his “constructive revenge”: helping children whose parents, like his, suffered grievous penalties for their devotion to radical and socialist causes.

Just before their execution, the Rosenbergs penned a final letter to their sons. They said they were “secure in the knowledge that others would carry on after them.” Others have, not least of all Robert Meeropol.

Dean Ferguson is an editor of Transformation, a newly launched literary journal. He lives and works in San Francisco.

|

| Print