|

“O there are times, we must confess To harboring a whim — we Like to picture old Karl Marx Sliding down our chimney” — Susie Day “Help fund the good fight. By contributing to MR, you help reinforce the left and reclaim the future.” — Richard D. Vogel To donate by credit card on the phone, call toll-free: You can also donate by clicking on the PayPal logo below: If you would rather donate via check, please make it out to the Monthly Review Foundation and mail it to:

Donations are tax deductible. Thank you! |

In July 2006, the Chicago City Council passed a “Big Box Living Wage Ordinance,” mandating that all retail stores larger than 90,000 square feet and operated by companies making more than $1 billion a year in revenue pay workers a minimum hourly wage of $10 per hour. The ordinance was vetoed by Mayor Richard Daley in September 2006, who said the measure would be harmful to the city.

The growth of big box retail is a mixed blessing to local communities. There is strong evidence that jobs created by Wal-Mart in metropolitan areas pay less and are less likely to offer benefits than those they replace. Controlling for differences in geographic location, Wal-Mart workers earn an estimated 12.4 percent less than retail workers as a whole, and 14.5 percent less than workers in large retail in general.1 Several recent studies have found that the entry of Wal-Mart into a county reduces both average and aggregate earnings of retail workers and reduces the share of retail workers with health coverage on the job. The impact is not only one of substitution of higher wage for lower wage retail jobs, but also a reduction in wages among competitors.2 As a result of lower compensation, Wal-Mart workers make greater use of public health and welfare programs compared to retail workers as a whole, transferring costs to taxpayers.3

Big box retail in general, and Wal-Mart in particular, also bring benefits to consumers in the form of lower prices. Studies of Wal-Mart prices find them to be 8 to 27 percent lower for food compared to major supermarkets. Just as competition from Wal-Mart has led competitors to reduce wages, it also leads them to reduce prices.4 Basker (2007) cites the results of a Pew Research Center Survey to conclude that poorer consumers disproportionately benefit from Wal-Mart’s lower prices.5 Furman (2005) makes a similar argument, and further states that Wal-Mart could not raise wages without raising prices which, he argues, would hurt poor and low-income consumers.6

To understand how a mandated wage increase would impact poor and low-income families, we need to understand both the size and distribution of any projected increase in consumer prices. We need to understand the economic status of Wal-Mart workers and consumers and how an increase would impact each group. If most Wal-Mart workers came from higher-income families and consumers from low-income families, a mandated wage increase might result in a net transfer away from low-income families. If the opposite is true, it might result in a net transfer to low-income families.

In this study we analyze how a higher wage standard would impact both Wal-Mart workers and consumers, and how those impacts are distributed across income levels. We use a $10 per hour minimum as the hypothetical wage standard for the analysis.

IMPACT ON WORKERS

What if Wal-Mart put in place a $10 per hour minimum wage for all its hourly employees in the U.S.? How much would it cost Wal-Mart, and how much of the increase would benefit workers in poor and low-income families?

In order to calculate the cost of a wage increase for Wal-Mart, we use detailed data on Wal-Mart workers’ starting wages and average pay in 2001 for 156 job titles from Richard Drogin’s analysis of Wal-Mart payroll data. Wages are adjusted to 2006 dollars using average annual wages reported by Wal-Mart. Although much of the variation in wages within the Wal-Mart workforce is captured by the job-based wage distribution, each job category has workers earning at different levels. To capture this added variation within job titles, we use household level wage data from the March 2006 Current Population Survey (CPS), and assumptions based on existing estimates in the literature on within company and between-company components of wage variance. We also use the March CPS to estimate the family income of Wal-Mart workers by statistically profiling them based on their wage levels, gender, full-time status and industry of work. For a full description of the methodology, see Appendix A in the full report. The key finding of this report — that a higher wage standard at Wal-Mart represents a progressive income redistribution even accounting for effects on consumers — is quite robust to a plausible range of assumptions we use in our analysis.

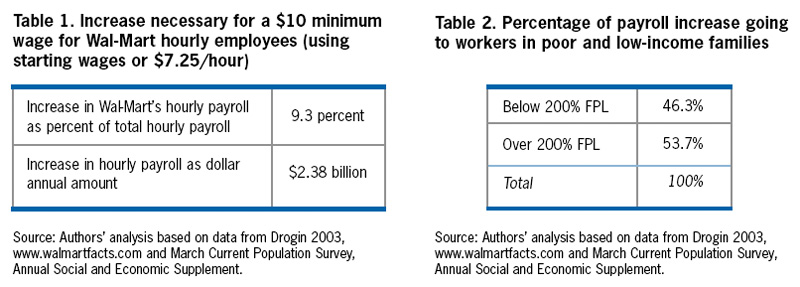

Based on the distribution of wages for the Wal-Mart workforce, we estimate that a $10 minimum wage would increase Wal-Mart’s total payroll for hourly workers by 9.3 percent (Table 1). With a total hourly payroll of 25.6 billion for the company in 2006, this comes to $2.38 billion per year. About 46.3 percent of this increase would go to workers with family incomes below 200 percent FPL (Table 2).

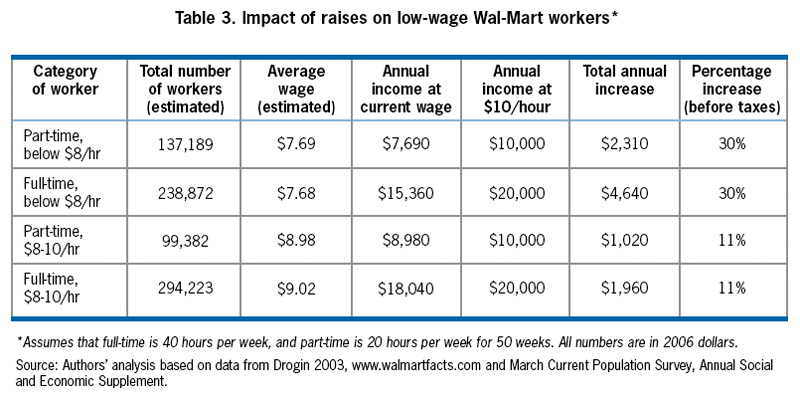

What would the raise to $10 per hour look like for the Wal-Mart workforce? Wal-Mart notes that its average hourly wage is $10.11. However, not all employees earn the average. In fact, payroll data from 2001 suggests that there is a good deal of variation in hourly wages by gender, race and job title. As shown in Table 3, adjusted for current income, workers currently earning below $8 an hour would receive a 30 percent wage increase on average, depending on the number of hours worked. Those earning between $8 and $10 an hour would receive an 11 percent wage average increase. In dollar amounts, the wage increase to $10 per hour would result in $2,310 to $4,640 average annual pay increases for workers with wages below $8 an hour, and $1,020 to $1,960 average pay increase for workers with wages between $8 and $10 an hour. (The range reflects the difference between full and part-time workers). The post-tax increase would be lower for some workers that qualify for the Earned Income Tax Credit, depending on the precise family income level.

The distributional impacts would be reduced to the degree that firms respond to the mandated increase by hiring more skilled labor. The empirical evidence on similar policies suggests such impacts would be small.7

IMPACT ON CONSUMERS

Another important question to address is how a $10 per hour minimum wage would impact consumer prices charged by Wal-Mart. It is not necessarily the case that Wal-Mart would pass on the total cost of a wage increase to its shoppers through higher prices. Part of the cost could be absorbed through accepting a lower profit margin; leveling or reducing management salaries and bonuses; and through improved labor productivity due to increased effort, lower turnover, and lower absenteeism.8 To the degree that Wal-Mart’s lower relative wages have led to greater opposition to the company’s expansion in urban areas, measures to respond to critics may improve the business climate for the company, opening new markets in urban areas and lessening the time needed to secure necessary zoning changes.

For the purposes of this paper, however, we examine the outermost case of what would happen if Wal-Mart were to pass the entire cost of the wage increase on to consumers.

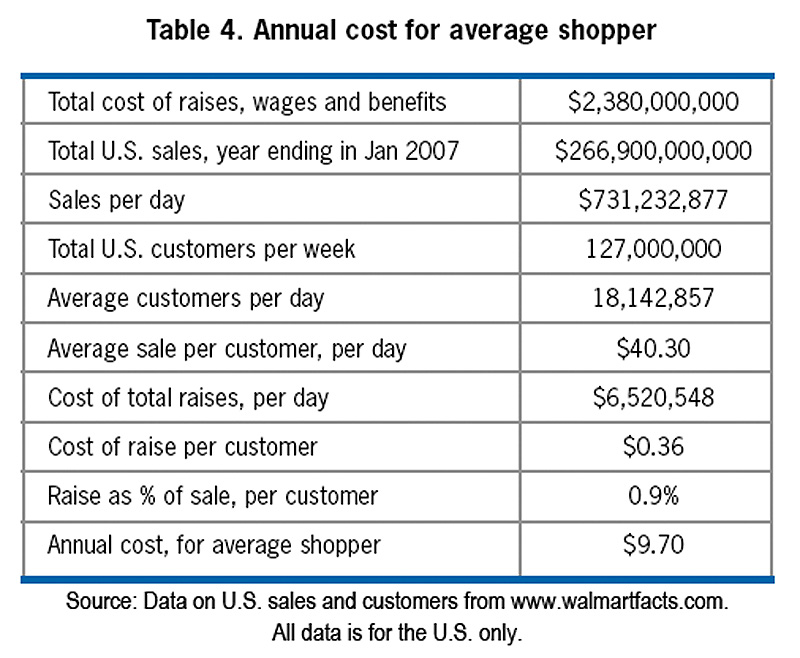

As we showed in the previous section, the cost for Wal-Mart of a $10 per hour wage increase would amount to $2.38 billion a year in payroll costs, or 9.3 percent of Wal-Mart’s current hourly payroll. If we distribute this among all consumers, we find that it amounts to 36 cents per shopping trip, for the average consumer, based on the annual sales and customer figures provided by Wal-Mart for 2006 (Table 4).

To estimate the impact per shopping trip, we use Wal-Mart’s annual U.S. sales data and weekly customer data. We divide sales by 365 and customers by seven to get the average sale per customer per day. We then divide the total annual payroll increase by 365 to get the cost of the wage increase per day.

Using Wal-Mart’s figures on U.S. sales and customers, we find that the average customer spends $40.30 per shopping trip, and makes 27 shopping trips per year, spending $1,088 annually at the store (Table 4). The 36 cent increase amounts to a 0.9 percent increase in prices. For the average shopper, this would result in a price increase of $9.70 a year.9

However, we are not only concerned with the average Wal-Mart shopper, but also with the low-income Wal-Mart shopper, and in particular, those low-income consumers who frequently shop at the store. How would these low-income shoppers fare if Wal-Mart were to increase its prices to recoup the costs of a wage increase?

The Nielsen Company provides a breakdown of Wal-Mart shoppers by household income using its Homescan Consumer Panel. The panel consists of a sample of 40,000 randomly selected households who use in-home scanning devices to record where they shop, what they buy, what they spend, and whether or not they used a coupon or took advantage of a store deal in their purchase of a product. Of the total households in the sample, 34,000 made at least one shopping trip to Wal-Mart during the year.10

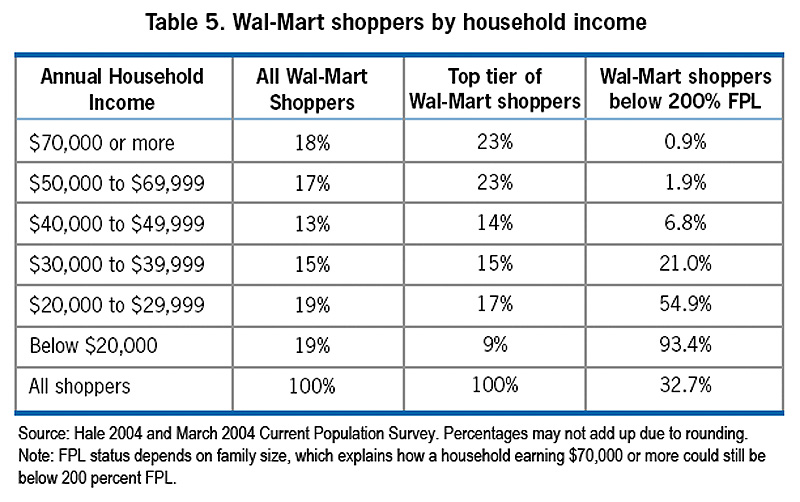

The Nielsen Company analysis shows that Wal-Mart shoppers are distributed across household income brackets, but disproportionately middle and lower income (Table 5). However, the distribution of top shoppers — the top 6.25 percent of shoppers who account for more than one-third of Wal-Mart sales — is skewed away from lower-income households. For example, while 18 percent of all Wal-Mart shoppers come from households with annual incomes of $70,000 or more, 23 percent of the top shoppers come from this bracket. In fact, almost half of Wal-Mart’s top shoppers come from households earning $50,000 or more in annual income.11 Data from the Current Population Survey allows us to estimate the share of shoppers in these household brackets who are in families below 200 percent FPL.12

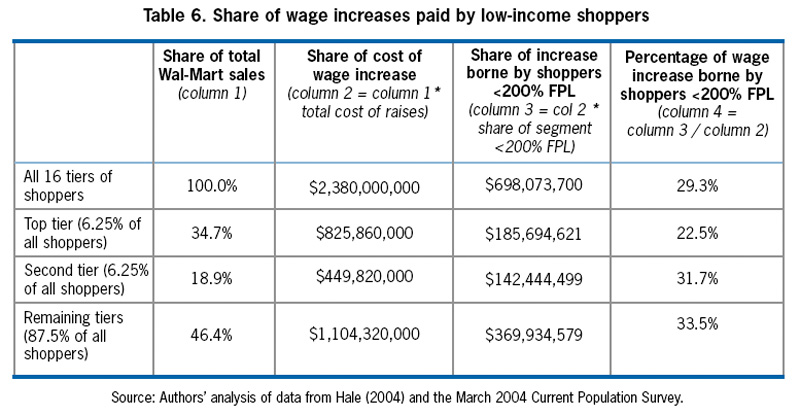

The top 6.25 percent of shoppers account for 35 percent of total Wal-Mart sales. The second 6.25 percent of shoppers account for 19 percent of sales. The remaining tiers — 87.5 percent — contribute 46 percent of sales (Table 6). We weight shoppers by their share of total Wal-Mart sales, to find the impact of the raises on low-income shoppers.

Overall, 32.7 percent of all Wal-Mart shoppers are in families with incomes below 200 percent FPL. If we weight these shoppers by their share of sales, we find that shoppers below 200 percent FPL would bear 29.3 percent of the wage increase (see Table 6). By comparison, 27.7 percent of the entire adult population is below 200 percent FPL.13

The two top groups, which make up 12.5 percent of all Wal-Mart shoppers, shop, on average, just over once a week at the store. We estimate that 27.1 percent of them are in families below 200 percent FPL. That means that 3.4 percent of all Wal-Mart shoppers are in poor and low-income families and are in the top two tiers of Wal-Mart shoppers.

To estimate the impact of a complete pass-through of higher wages on high-spending, low-income shoppers, we calculate the proportion of sales that the top two segments of low-income shoppers spend at Wal-Mart, to get their average spending per shopping trip. We find that frequent shoppers living at less than 200 percent FPL spend $36.8 billion a year at Wal-Mart, and would be responsible for approximately $328 million of the wage increase. This amounts to approximately $1.47 per shopping trip. Top tier shoppers average between 57 and 60 shopping trips a year, and spend approximately $164 per trip, or $9,866 per year. The $1.47 price increase would amount to an increase of $87.98 a year, or approximately $7.33 per month.14

CONCLUSION

Should policy makers consider supporting legislation that would raise wages at Wal-Mart? Should they be concerned that low-income shoppers will bear the cost if Wal-Mart is required to increase its minimum wage to $10 an hour?

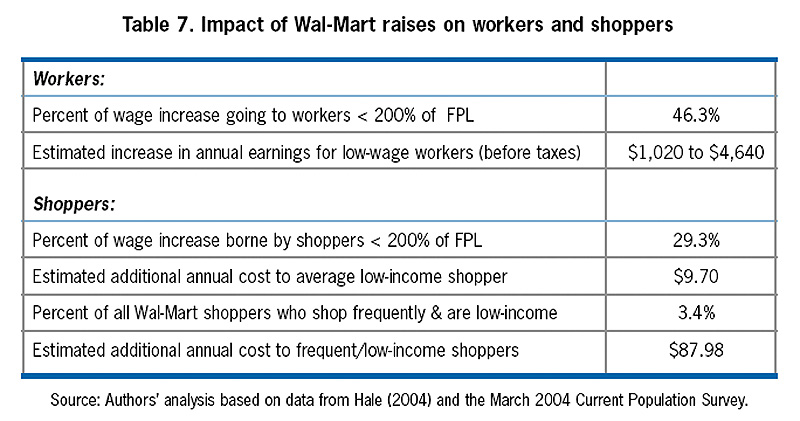

Our data suggests that a $10 per hour minimum wage standard at Wal-Mart would be effective in aiding lower-income families. If Wal-Mart increased its minimum wage to $10 per hour, 46.3 percent of the income gain would accrue to workers with wages below 200 percent FPL. These low-wage workers could expect to earn an additional $1,020 to $4,640 a year in income.

If Wal-Mart passed on 100 percent of the wage increase to consumers through price increases, which is unlikely, the impact for the average Wal-Mart shopper would be $9.70 a year (Table 7). We estimate that 29.3 percent of the impact of the price increase would be borne by shoppers with incomes below 200 percent FPL. Frequent, low-income shoppers, who account for 3.4 percent of all Wal-Mart shoppers, might see larger costs, up to $87.98 a year. In higher wage labor markets the impacts would be lower for both workers and consumers.

Finally, we should consider the impact of a mandated wage increase on the economic viability of big box retailers. Some analysts suggest that Wal-Mart could not just raise wages, and prices, given that they operate in a competitive environment. However, the Big Box Ordinance would require all large retailers to operate under the same standards. Steve Hoch of the Wharton Business School argues that the proposed Chicago Big Box Ordinance is unlikely to have a negative impact on retailers or Chicago: “The standard argument by the retailer is that they can’t afford to do it, but if everybody has to, then the playing field is level.” His argument is born out by recent research on the economic impacts of minimum wage and living wage ordinances.

In conclusion, big box living wage laws provide a means of capturing the positive benefits to consumers of the big box retail model, while mitigating the negative impacts on workers.

ENDNOTES

1 Arindrajit Dube and Steve Wertheim. “Wal-Mart and Job Quality: What Do We Know and Should We Care?” October, 2005.

2 Arindrajit Dube, T. William Lester, and Barry Eidlin. “Firm Entry and Wages: Impact of Wal-Mart Growth on Earnings throughout the Retail Sector.” August, 2007; David Neumark, Junfu Zhang, and Stephen Ciccarella. “The Effects of Wal-Mart on Local Labor Markets.” October 2005.

3 Arindrajit Dube and Ken Jacobs. “Hidden Cost of Wal-Mart Jobs: Use of Safety Net Programs by Wal-Mart Workers in California.” August 2004.

4 Jerry Hausman and Ephraim Leibtag. “Consumer Benefits from Increased Competition in Shopping Outlets: Measuring the Effect of Wal-Mart.” 2005.

5 Emek Basker. “The Causes and Consequences of Wal-Mart’s Growth.” 2007. The Pew Survey found that 53 percent of respondents with annual earnings under $20,000 reported regularly shopping at Wal-Mart, compared with 33 percent of those with annual incomes above $50,000. (Pew Research Center 2005). Note that the Pew data does not control for the reasons shoppers gave for frequently shopping at Wal-Mart; it is possible that low-income shoppers shop more regularly at Wal-Mart because they have fewer stores to choose from, or may lack transportation to reach other stores as easily. Consumer data collected by Neilson shows that those surveyed say that their main reason for choosing Wal-Mart was location (34 percent). Twenty-five percent of respondents say their main reason is low prices (Hale 2004).

6 Jason Furman. “Wal-Mart: A Progressive Success Story.” November 28, 2005.

7 Michael Reich, Peter Hall, and Ken Jacobs. “Living Wage Policies at the San Francisco Airport: Impacts on Workers and Businesses.” 2005; David Fairris, David Runsten, Carolina Briones, and Jessica Goodheart. “Examining the Evidence: The Impact of the Los Angeles Living Wage Ordinance on Workers and Businesses.” 2005.

8 A Bank of America analysis estimates that the after tax impact of a $0.50 per worker wage increase by Wal-Mart would be an increase of $0.013 earnings per share. David Strasser and Camilo R. Lyon. Bank of America Retailing Report on Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. March 8, 2007. While little research has been done on the impact of reputation on stock price, Communications Consulting Worldwide suggests that in the case of Wal-Mart it could be significant. Pete Engardio, “Beyond the Green Corporation,” BusinessWeek. January 29, 2007; Jared Bernstein and L. Josh Bivens. “The Wal-Mart debate: A False Choice between Prices and Wages.” June 2006.

9 Todd Hale, “Understanding the Wal-Mart Shopper.” 2004.

10 Ibid.

11 We compared the Nielsen data to other sources to check for consistency. Mediamark Research conducts a face-to-face, in-home survey of 26,000 consumers a year. Their 2004 data found a greater share of Wal-Mart shoppers from higher-income households than the Nielsen data. For example, Mediamark data shows 49.7 percent of all Wal-Mart shoppers have a household income of $50,000 or more (compared to 35 percent in the Nielsen data). Mediamark finds that 28 percent of households have income of $75,000 or more, while Nielsen finds 18 percent of $70,000 or more. (Mediamark also finds 15.4 percent of shoppers from households with $100,000 or more in annual income; Nielsen does not provide this data). The Pew Research Center data also finds shoppers more skewed to higher-income households than does the Nielsen data. The Pew data (2005) is more recent than the Nielsen data, but finds 27 percent of shoppers from households with $75,000 or more in annual income, and a total of 46 percent with household income of $50,000 or more. This suggests that it is unlikely that Nielsen Company undercounts low-income shoppers.

12 To find the percentage living in poverty, we use the March 2004 Current Population Survey ASEC (Table 6). In order to make overall consumers more representative of Wal-Mart consumers, the sample was re-weighted to make each state’s percentage of U.S. households equal to each state’s percentage of U.S. Wal-Mart stores. The 2004 March CPS data reflects information for the previous year, which corresponds to the Nielsen Company data, which is from 2003.

13 Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement (2006).

14 For a family of four living at 200 percent of the federal poverty level, this price increase would amount to 0.2 percent of

their gross annual income. This assumes a family of two adults and two children. The 2006 preliminary weighted average

poverty threshold, as defined by the Census Bureau, is $41,260 for a family of this size.

Ken Jacobs is Chair of the Center for Labor Research and Education at University of California at Berkeley. Arindrajit Dube and Dave Graham-Squire are researchers at the UC Berkeley Labor Center. Stephanie Luce is an associate professor and research director at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst Labor Center. (A full copy of this report, with appendices, is available at laborcenter.berkeley.edu/.)

|

| Print