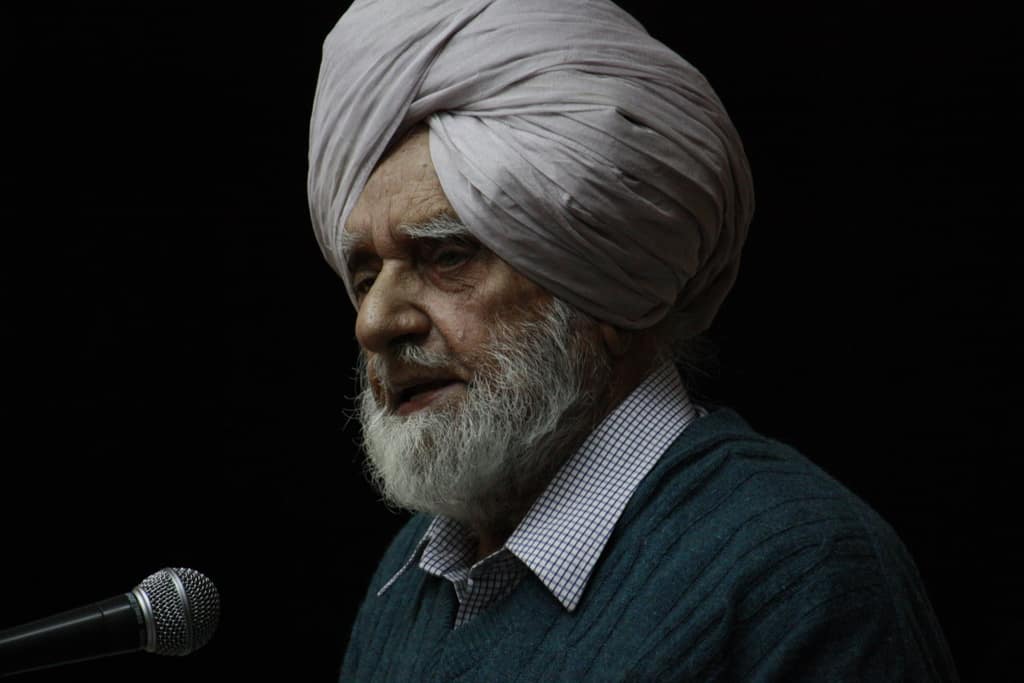

Address to the journal Itihasbodh at Allahabad on March 8, 2007.

I have been asked to speak on ‘Future of Socialism’. What I am going to say is based on my recently published book, Crisis of Socialism — Notes in Defence of a Commitment, which may be referred to for the detailed argument in support of the propositions I am going to advance with the help of passages culled from this book. I am going to deal with the question in four separate but interrelated segments of my address.

During the heady, rebel days in the late sixties, students of Paris used to ask of everyone who would address them to first tell them: ‘where do you speak from?’ For every speaker, inescapably speaks from a particular philosophical-political standpoint and owes it to his audience to publicly state it. It is only fair to acknowledge that I am going to speak from the standpoint of Marxism, rather Marxism as I understand it. For I have no pretensions to scholarship in Marxism. I picked up some on the way and have found it useful not only in my politics or profession as a teacher, but in living my life as well. This last is not just a formal statement. Knowing Marx does make a difference to what sense you make of life, how you understand, live and act in the world. ‘Indeed, I must confess that Karl Marx made a man of me’, is how George Bernard Shaw once put it. Marx, therefore, is important to me and, I believe, he is important to all of us, today more so than ever before, if for no other reason than this: the world we are living in is a capitalist world, more capitalist than ever before after the Soviet collapse, and Marx more than any other human being, then or now, devoted his life to explaining the reality of this world and his achievement here remains unrivaled. In one sense, this is what I am going to speak about, for socialism, properly understood, is a historically necessary and possible negation of capitalism.

I

No discussion of socialism today, least of all its future, can bypass what happened in the erstwhile Soviet Union. What we have here, as I have argued at length in my book, is a failed revolutionary experiment: a grievously deformed socialism that was built and the final crisis and collapse of the sui generis class exploitative system it had ultimately degenerated into — all of which is fully amenable to a Marxist explanation in terms of its method of historical materialism and class analysis. In other words, what failed in Soviet Union was not socialism but a system that came to be built in its name. I have no time to discuss this subject here. Immediately I would only like to emphasise the need for socialists to understand the why and how, and the implications, of what happened in the erstwhile Soviet Union.

It is indeed imperative for socialists who wish for a future beyond capitalism to understand what has happened, what was built and what has failed as socialism in the Soviet Union. They must assess the costs and consequences of this failure, the collapse of what we have described as ‘actually existing socialism’, and some others as ‘authoritarian communism’ — though they must do so fully mindful of the costs and consequences of ‘actually existing capitalism’ or ‘authoritarian capitalism’ which has rushed in to pick up the pieces. It was certainly mistaken to see the struggle for socialism in our times as a contest between ‘the socialist world’ and ‘the capitalist world’, as official Marxism in the post-1917 period made it out to be. It was, as always, an international class struggle with several more or less important fronts. The countries of ‘actually existing socialism’, while it lasted, were only one front of this struggle, and while they did condition or influence this struggle, positively as well as negatively, they did not determine or settle the question of its outcome. Nor does the collapse of these countries now, or their return to the capitalist fold, in any way settle the question of the future of socialism — the struggle still goes on and will, so long as capitalism lasts. Nevertheless, these countries constituted what was in many ways a most important front of the ongoing international class struggle and their collapse demands that socialists understand and come to terms with it. If they no more need to carry the burden of a deformed and degenerated socialism or be answerable for its ugliness and cruelties, the burden of a genuine, Marxist explanation of its collapse has still to be carried by them so that our people know the truth and appropriate lessons are drawn for struggles of the future. . . .

We need this explanation not only to learn the right and not wrong lessons from what has happened, but even more because in the absence of our explanation, it is their, the enemies’ explanation which will continue to prevail, and this is: ‘socialism has failed’. What is more, we need it to prevent them from taking our history from us. For the ideologues of capitalism, even as they have pronounced the ‘end of socialism’ and with the post-modernists even deny the ability to learn from history, are busy depicting the October and what followed, an entire era of people’s heroic struggles and achievements, as nothing but a costly aberration in history. Indeed, defending or reclaiming our history is today in itself a revolutionary project for us, as part of our assessment of what has happened in the Soviet Union. . . .

The lessons, often bitter ones, have to be drawn from the past. This is necessary to face reality and rebuild the required politics and culture on the Left. But it is equally necessary to be properly balanced about it. In other words, it also needs to be recognised that this past is not entirely a bitter heritage. Our assessment or self-accounting must not throw any baby out with the bath water. . . .

An assessment or reassessment of the experience of Soviet Union, culminating in the collapse of history’s first great experiment in socialism and of the whole communist movement associated with it, even when not led or dominated by it, is obviously important for socialists everywhere, in the North as well as the South. But those who especially need to master the lessons of this experience are the leaders, and even more the militant cadre, of the communist parties for whom Soviet Union was a decisive point of reference and identity, whatever the differences that may have emerged in the later period. In the West, unable or unwilling to find answers to the Soviet collapse and related problems from within Marxism, most of these parties have simply abandoned the socialist project and opted for the social democratic road. Elsewhere, mostly in the Third World, though remaining formally communist, they are confused and disoriented by what has happened and, unable to transcend the orthodoxies of official Marxism, are content to blame it all on Khrushchevite revisionism, betrayal of a Gorbachev or secret machinations of U.S. imperialism and its CIA. Even the Marxist-Leninist communist formations, or those holding on to the old orthodoxies of Chinese vintage, have, by and large, failed to go beyond this much too simplistic and shallow understanding. Unless the opportunity is now seized to turn to authentic, creative Marxism to understand the crisis and collapse of Soviet socialism and this understanding made central to a rethinking of the whole question of the long-current reformist or ultra-Left practices in the movement, the momentum of the past may keep these communist parties going, but, with the old leaders and credibility born of past struggles or gains fading out and the failure of any new radical recruitment, they can only stagnate, or continue to decline down the road of economistic practices, electoralist reforms and even pragmatic adjustments within the ongoing capitalist globalisation; and the Marxist-Leninist or Maoist formations, their avowed revolutionary commitment notwithstanding, will remain the sectarian movements they are, wrangling with each other and quarantined within their limited areas of influence. Though communist in name, these parties and formations will have lost the opportunity to recover and become a politically effective force on behalf of socialism. . . .

For socialists in the Third World, including those who call themselves communists, the Soviet experience has an added, rather exceptional importance. Classical Marxism, with its perspective of construction of socialism in advanced capitalist countries and on an international scale, had, apart from some general principles, little to say to the Russian Bolsheviks as they set out on their unanticipated journey in an entirely uncharted territory: a struggle for socialism in a single backward country, in the midst of unremitting hostility of internationally dominant capitalism led by its most advanced sectors. Theirs was a pioneering effort. Insofar as the cause of its failure lies, along with the force of objective circumstances, in the inadequacies of theory and practice for this unprecedented task, the Soviet experience has invaluable lessons for revolutionaries in the Third World as, like Russia, their poor and backward countries, in this period of renewed global capitalist domination, seek a better, necessarily socialist, destiny for themselves. . . .

What has happened in the former Soviet Union does not in any way invalidate Marx’s argument for the necessity and possibility of a socialist negation of capitalist social order. Only the struggle for socialism is turning out to be far more complex and difficult than he ever visualised. Socialists of course have no illusions that the struggle for socialism is going to be easy or expeditiously successful. After the first failure, it will be far more difficult in many ways than before, it is going to be a long detour to socialism next time. But they have no reason to feel gloomy about the prospects either. The material conditions are more favourable and objective compulsions far stronger than appeared possible a few years ago, and the constituency for the socialist cause can only grow as capitalism shows itself increasingly incapable of coping with the crises it produces. . . .

II

It can be legitimately argued that the reasons which in the first place gave rise to the movement for socialism still hold, more so at the beginning of this century than they did at the beginning of the last or at any time earlier. Capitalism remains a deeply exploitative and ecologically disastrous way of organising social life. Apparently triumphant, capitalism continues to operate under the same structural compulsions, producing the same catastrophic consequences as before. It remains ridden with crises and congenitally unable to subordinate its achievements to the needs of human beings, unable, despite its prodigious productive abilities, to offer even bare survival to vast majorities in the world it dominates. Despite its current apotheosis, capitalism has resolved none of the problems which have for more than a century and a half given sustenance to socialist aspirations and struggles. The logic favouring a worldwide transition to socialism remains as compelling today as it has ever been.

The collapse in the Soviet Union does not in any way change this logic, except that the economically exploitative, morally repulsive and ecologically unsustainable character of capitalism is now more apparent than at any time in its history. . . .

The objective conditions and more than an embryonic subjectivity at individual and mass organisational levels exist for the reconstruction of a socialist opposition to the currently dominant capitalist system. In the West the euphoria over ‘no alternative’ is long over. The declaration of ‘the end of history’, like similar declarations in the past, stands rejected as so much silliness. The long moment people thought typical, the welfarist capitalism, is recognised as not typical, typical is the harsh reality they are now experiencing. People are learning the hard way what capitalism is really about. Just as in the hinterlands of global capitalism, ravaged by ‘globalisation’ and subjected to the new domination of America, people are learning anew about capitalism and imperialism, and about the compradorism of their own ruling elites. The question of an alternative is back on the agenda, and in different shapes and forms, in however confused or muddled a manner, anti-capitalist struggles are being resumed in different parts of the world. These struggles may not produce a remake of the previous century. History does not repeat itself, we are told. But ‘history is more imaginative than we are’, Marx had said. History certainly has its surprises — and revolutions by the oppressed and exploited are among them. . . .

Revolution is not only armed struggle or insurrection, though it still cannot be ruled out. It does not at all help to see revolution as a punctual moment in history or in terms of iconic images like the taking of the Winter Palace or storming of the Bastille. Revolution is best understood as a complex process — with special complexities of its own in regimes of bourgeois democracy. And however we understand it, we cannot predict the practical and theoretical forms of the revolutions of the future. But we know the surprises that vicissitudes of world history brought us in the twentieth century. And there is no reason to doubt that this one will bring more. The inventiveness of masses in revolt has been and will continue to be beyond the imagination of the most sensitive scholar or philosopher. . . .

Revolution is not over. The basic conflicts between classes, between the oppressed and the oppressors, between a new and the old social order, will not cease because Soviet Union has ceased to be and a Fukuyama has announced the ‘end of history’. The dynamics and forces which generated the revolutions of the twentieth century remain as they were in the past. The end of ‘historical communism’ has not put an end to poverty or to people’s thirst for justice. The poor and forsaken of the Third World still hope for a better life. Not exactly enthusiastic over revolutions, past or future, Fred Halliday, in his recent study on the subject, has yet pointed to ‘the enduring inability of those with power and wealth to comprehend the depth of hostility to them’ and ‘the ability of history . . . to surprise’, and written: ‘the agenda of the revolutions of modern history is still very much with us because the aims they asserted . . . are far from having been achieved.’ This leaves revolution still on the agenda of history. Revolution remains the vital truth, the unfinished story of our times — in whatever shape or form and over however long a period the rest of the story may be told. . . .

The story is in fact already being told in the resumed world revolutionary process which, after the initial setback following the failed experiment in the Soviet Union, is again positing socialism as the necessary and possible future for humankind. As they struggle to forge extra-parliamentary sanctions to defend their Bolivarian revolution against American imperialism and its local allies, the Venezuelans are speaking of building ‘socialism of the twenty-first century’ and, inspired by Cuba, the pink is threatening to turn red elsewhere in Latin America. Fighting their ‘People’s War’ and now struggling to win the battle of democracy, the Maoists in Nepal seek self-reliant development ‘oriented towards socialism’. As the struggle against globalization sharpens in the West, the New Yorker writes of ‘The Return of Karl Marx’ and in Europe voices are heard asking for new experiments in socialism. Never a narrowly conceived class project, socialism today stands poised, as never before, to be ‘the movement of immense majority in the interest of immense majority’ as Marx had proclaimed in the Communist Manifesto.

III

The collapse in Eastern Europe and Soviet Union has led any number of scholars, journalists and politicians, ideologues and writers of all śorts, to play zero sum games. If socialism has lost, then its antagonist, capitalism, must have won. If planned socialist economies have broken down, then their binary opposite, free-market capitalism must have triumphed. Apart from its utterly reductionist and adversarial and obviously questionable logic which, equating what was built in Soviet Union with socialism as such, conflates its failure with a victory for capitalism, such an assessment of the situation is not only logically flawed, it is false on empirical grounds as well. On any objective assessment, at the end of its five centuries old existence, global capitalism is a very much failed system today. The evidence of this failure is starkly visible in every part and aspect of contemporary capitalist world. It is visible in the impoverishment and immiseration on the rise just about everywhere in the world; in the official statistics on rates of unemployment, poverty, homelessness, and hunger; in the sullen slums of major cities of Western bourgeois democracies, proliferating urban ghettos of the gritty capitals of former Soviet bloc countries and the warrens of teeming tumble down shanties of the peripheral South; in the gross inequalities of the world, the wretchedness of the impoverished and excluded within the rich Western societies and the huge mass of misery in the poorer countries; in the morally intolerable and socially unnecessary suffering — what Bourdieu has called la misere du monde — produced by capitalism everywhere. . . .

The ‘actually existing socialism’ — which was not Marx’s socialism whose possibility remains open — has, of course, failed. But, surely, the ‘actually existing capitalism’ — which is the only kind of capitalism possible — has not been the success it is made out to be. In any objective judgement, capitalism too has been a failure in our times. Other considerations apart, capitalism has been a failure in terms of possibly the most legitimate criteria for assessing the performance of a social system: ‘fullness of employment’ and ‘goodness of employment’ of the actual and potential resources available in society. Never before in human history has the gap between society’s potentiality and society’s performance been so immense as it is today in capitalism’s current stage of development. Evidence is there in the extraordinary productive capacity that three successive industrial revolutions have put at the disposal of humankind and the poverty and illiteracy, squalid slums and homelessness that are the lot of millions of families in the wealthiest countries of the capitalist world and the hunger and misery of hundreds of millions of people, living out their empty and barren lives in the hovels of the peripheral or semi-peripheral poor countries of the Third World. The Third World today is indeed a monument to the failure of capitalism in our times. . . .

As hinted above, there is a difference between the two failures that needs to be specifically noted. Socialism may have failed for the time being, but it remains the alternative if humankind would survive and hope for a safe world and life worthy of human beings. It bears repeating that the unacceptable economic, moral and ecological consequences of capitalism, its failure ranging from unemployment, poverty and inequalities to barbarisation, at home and abroad, are not aberrations of the system or ‘negative’ effects produced by specific circumstances or ‘mistaken’ policies. They are the product of capitalism’s unreformable and uncontrollable systemic or structural logic, the logic of exploitation and polarisation immanent in the system itself. Therefore these ‘effects’ are permanent, even though they are diminished in certain phases and increased in others. They are thus essentially irremediable. In other words, the failure of capitalism in our times has a systemic or structural necessity or inevitability about it. In contrast, there was no systemic or structural necessity about the failure of socialism in the Soviet Union. With politics commanding the economy, socialism simply has no structural logic or ‘laws’ similar to what market-based capitalism has. Socialism failed primarily due to the inadequacies of theory and practice, to the mistaken choices that the Communist parties in power made. Apropos the failure of communist regimes (and Social Democracy in Europe), Gabriel Kolko has written: ‘Their consistent failure to redeem and significantly (as well as permanently) transform societies when in a position to do so is testimony to their analytic inadequacies and the grave, persistent weaknesses of their leadership and organisations. It is this reality that has marginalized both social democracy and communism in innumerable nations since 1914, providing respites through the century to capitalist classes and their allies that otherwise would never have survived socialist regimes that implemented even a small fraction of the reforms outlined in their program.’ While this may be bending the stick too far the other way, the important point is that socialism’s was essentially a human failure. Which had nothing inevitable about it. The lessons learnt from this failure will help whenever or wherever the attempt is made next time. Socialism, therefore is not just the alternative to capitalism, it remains a real choice for humankind. . . .

Socialism as they built it in the Soviet Union has failed. Elsewhere, capitalism too has been a failure. That both socialism as we have known it and capitalism as it has existed have failed in our times suggests that we may well locate the question of ‘Future of Socialism’ in the problematic of epochal transitions, in this case the transition from capitalism to socialism/communism. In other words we have a situation where the old has exhausted its positive possibilities and the new is having problems being born. Gramsci had once written, of course of a different historical juncture: ‘The old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear’. These ‘morbid symptoms’ are, to a greater or lesser degree, there all over the advanced and less advanced capitalist countries today, as good an evidence as any of the deep crisis of the capitalist civilisation, of the ultimate failure of capitalism in our times. . . .

What we are indeed witnessing today is the end of an epoch, the epoch of transition to capitalism. Over these five hundred odd years, as capitalism expanded to structure and restructure an unequal world of core, semi-periphery and periphery regions in terms of economic strength and benefits, at each stage of this expansion, capitalism was able to overcome its permanent contradictions, but not without worsening the situation for itself for their overcoming in future. Now with the possibility of further expansion virtually exhausted, these contradictions are difficult to overcome as in the past. They are manifesting themselves all the more violently with truly disastrous consequences for the people that suggest the passing away of the epoch of capitalism’s domination. Even at its best capitalist development has been a process of ‘creative destruction’, to use Schumpeter‘s famous phrase. As accumulation takes place, competition forces firms to be creative in order to survive, and those firms that are not creative are destroyed. In a world of markets and competition, winners are matched by losers, and creation and destruction become one and the same. Losers, however, have not been simply impersonal firms or abstract inefficient technologies. In the real world, losers have been people, sometimes capitalists, but always working people, individually and as communities. ‘Creative destruction’ has meant the unemployment of real workers, the destitution of real communities, devastation of the environment, and disempowerment of the people. The destructive aspect of capitalism’s ‘creative destruction’ has now reached a point where the historical raison d’etre and justification that capitalism, as a mode of production, once had, has disappeared and we can legitimately speak of capitalism living beyond its time, beyond the period of its historical legitimacy.

Capitalism’s achievements are now all in the past, its future promises only disasters for humankind. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels had written of class struggle ending ‘either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large or in the mutual ruin of the contending classes.’ The great class struggles of the twentieth century have obviously not resulted in ‘a revolutionary reconstitution of society’. What Marx and Engels saw as ‘the common ruin of the contending classes’ is already on in the world. Economies everywhere in shambles; obscene wealth alongside abject poverty and wanton waste of resources; widespread collapse of law and order; senseless regional and ethnic conflicts; new wars between or within nations almost on a daily basis; spread of weapons of mass destruction and threat of terrorism on a global scale; an all-engulfing ecological crisis — all this in fact points to the common ruin of more than the contending classes as a very realistic prospect in the historically near future. The epoch of capitalism may well end up in ‘the total destruction of humanity’, the possibility predicted by Marx in 1845 — a perspective that Rosa Luxemburg later summed up in the dictum: ‘Socialism or barbarism’. Modifying Rosa Luxemburg’s dictum in relation to the dangers we face, Meszaros has suggested adding to ‘socialism or barbarism’, ‘”barbarism if we are lucky” — in the sense that the extermination of humankind is the ultimate concomitant of capital’s destructive course of development.’ Such an outcome, ‘the extermination of humankind’, is implicit in the uncontrollable accumulative logic of capitalism. It has been rightly pointed out that the truth about capitalism today is not that it is the ‘end of history’, as the bourgeois ideologues want us to believe, but that its continued existence can really bring on the end of human history. . . .

As suggested above, taking ‘the longer view’ of things, the present day defeats and reversal of socialism are best viewed as part of the zigzag that the epochal transition from capitalism to socialism is bound to be. . . .

The twentieth century opened with global capitalism’s total domination of the world. Then, as anticipated by Marxian analysis, indeed by Marx himself, came the socialist revolutions of the twentieth century — the European revolutions in the aftermath of the First World War (of which only the Russian Revolution survived), in Eastern Europe after the Second World War, and then in China, Korea, Cuba, Vietnam and elsewhere — taking approximately a third of world’s population and territory out of the capitalist system. Socialism does not take root and grow within the confines of capitalist society, as capitalism had done under feudalism. It is a new beginning, a society best built on the material basis provided by capitalism. But now these poor and backward countries were called upon to build socialism where this basis hardly existed. It was a task for which they were most ill-prepared. Even so, as these countries struggled to build, and other revolutionary regimes and movements professing Marxism and committed to socialism emerged in Africa and elsewhere, for a long time the contest between capitalism and its post-revolutionary rival claiming to be socialist seemed to be close and of uncertain outcome. After the events of the recent past, it may be that the visible future belongs to capitalism. But such perspective is relatively new. For most of the century, it was far from clear that capitalism would survive into the third millennium. Now it is the post-revolutionary rival claimed to be socialism that has failed even to last till the end of the second millennium. This, however, is not any end of the earlier perspective. The Soviet experiment in socialism has failed because the conditions, both objective and subjective, were most unfavourable for it. There was the initial economic backwardness, then internal class war and armed and unarmed foreign intervention, global capitalism’s continuous effort to prevent any successful construction of socialism. Decisive in its own way were the factors of inadequate and often erroneous theory that guided, or misguided, this experiment and poor political leadership. But it is important to recognise that what has been tried and failed is not socialism but history’s first serious effort to build socialism. The reasons that produced the cause of socialism as well as the revolutions aimed at its achievement are still very much there. There is no reason to presume that new revolutions, surprising as ever for the dominant capitalism, will no longer take place and new efforts to build socialism will not be made. And even less reason to presume that given favourable circumstances, more adequate theory and better political leadership, such efforts will not succeed. . . .

Here a look at capitalism’s emergence and spread can be quite instructive. Scholars have pointed out that the late Middle Ages witnessed not one but several promising yet false starts for capitalism. But weak and divided, they lacked the stamina to survive in the hostile, predominantly feudal environment of the period. Smothered by surrounding feudalism, the emerging capitalism simply failed to catch on. It was not until centuries later that a new conjuncture emerged in which a budding capitalism, benefiting well from its earlier abortive appearances, could take root and grow powerful enough to fend off its enemies and survive, to finally arrive as it did in England and other Atlantic societies. Once arrived the struggle with feudalism still continued, a struggle between two actually existing social formations for supremacy, i.e., for state power (monopoly over the means of coercion) and the right to organise society in accordance with their respective interests and ideas. Moreover the process was a prolonged one in which the ‘new’ social formation had ample time to prepare itself, both economically and ideologically, for the role of undisputed dominance. It is thus that capitalism grew and developed into the globally dominant system of our times, till socialism made its first efforts to make a breach into it, an effort which has now failed. . . .

But the failure of history’s first socialist effort does not mean that more successful future efforts are impossible. The evidence of history suggests otherwise. As we have just noticed, it was only after many centuries of turmoil, through a long process of advances and retreats, that capitalism established itself as the dominant world economic system. In the centuries-long struggle between feudalism and capitalism, there were many ‘triumphs of feudalism’, but in the long run, capitalism finally prevailed. So in the case of the transition from capitalism to socialism, the struggle may continue for centuries. There have been, and undoubtedly will be, other ‘triumphs of capitalism’, but in the end socialism may yet prevail. By historical standards, a few centuries is not a long time and socialism has existed for only a very short time. It is certainly mistaken and premature to superficially extrapolate from the developments of the recent, historically limited, past and speak of the ultimate failure of socialism, to take an entirely bleak view of its future prospects. It is certainly not justified to regard the Soviet effort as only a ‘heroic but tragic experience’, ‘an abortive search for an impossible short cut’, a ‘parenthesis’ or ‘interlude’ in the history of capitalism, or, as in Stefan Heym’s phrase, merely a ‘footnote in history’, and so on. Rather dismissive in nature, such assessments tend to suggest a failure of socialism as such. On the contrary it is far more legitimate to argue that in view of the epochal nature of the transition involved, the Soviet collapse does not mean the end of socialism but only the end of world’s first large-scale attempt to transcend capitalism and build a socialist society. In the larger perspective of the next century or two, the developments since the 1920s can be better understood as a disastrous but still educative false start and the current crisis of socialism as a period of temporary retreat in the epochal transition to socialism. Therefore, if we believe that capitalism needs to be negated in socialism, that the underlying ideas and ideals of socialism provide the only possible framework for a decent human society, we certainly don’t have to abandon hope simply because the first attempts to realise them in practice — under very difficult and unfavourable conditions, it should be noted — proved unsuccessful. We can and must still hopefully struggle for socialism and refuse to accept capitalism as the inescapable destiny for humankind. It is thus that the contest between these two approaches to human social development is still unsettled. Its outcome remains open. In a long-term historical perspective, 1917, as Goethe said of 1789, may yet mark the beginning of a new epoch in the history of humankind. . . .

But this ‘long-term’ is today loaded with a problematic. Once available to capitalism for it to emerge, consolidate itself, and grow dominant, time is no longer so available to socialism — which, incidentally, also has most serious implications for the future of humanity. The reason lies in the growing ecological crisis in the world, where the accumulative logic of capitalism now threatens the very existence of human kind on the planet, earth. . . .

Capitalism has indeed shown remarkable resilience and survived beyond what can be described as its historical time. But its survival has now put a question mark over the future of humankind. Hobsbawm has written: ‘If humanity is to have a recognisable future, it cannot be by prolonging the past or the present. If we try to build the third millennium on that basis, we shall fail. And the price of failure, that is to say, the alternative to a changed society, is darkness.’ ‘Darkness’ yet does not capture the full gravity of what lies ahead. Caught in a global structural crisis, capitalism has become more creative than ever in unleashing its destructive potential. Its accumulative logic and America-led global politics are threatening humanity with unheard of ecological disasters and nuclear exterminism. With capitalism, humanity is indeed headed for a collective suicide and destruction of the earth itself. Socialism, therefore, is not just ‘a changed society’, a superior social order, it is today the necessary defence of humanity and our planet earth. This in its own way makes socialism all the more possible as an alternative to capitalism. Alternatives are discovered or invented, or even recovered, when it becomes clear that we cannot survive without them. So it is now with socialism. Pointing to the human tragedy that capitalism’s continued existence now portends for humankind, this is how Chomsky has put it in his characteristically simple manner: ‘At this stage of history, either one of two things is possible. Either the general population will take control of its own destiny and will concern itself with community interests, guided by values of solidarity, sympathy, and concern for others, or, alternatively, there will be no destiny for anyone to control.’ . . .

Years ago, the French students in their May-June uprising of 1968 expressed this sharp contrast of alternatives magnificently in their slogan: ‘Be practical! Do the impossible!’ Marcuse had suggested that the new generation that faces the next (that is, twenty-first) century needs to add to this demand ‘the more solemn injunction: If we don’t do the impossible, we shall be faced with the unthinkable!’ The ‘unthinkable’ today is more than mere ‘descent into barbarism’. What is at stake is the actual existence of the world, and with it of the human species. And the task, as eco-feminist Francoise d’Eaubonne, paraphrasing Marx has said, is ‘to change the world . . . so that there can still be a world’. Socialism is precisely the changed world we need. Once the promise of liberation, socialism has now become a question of survival too. The human species needs socialism not only to realise its potentials but even to survive. That is how the chances of survival and realisation of the potentials of both the human species and socialism have come to be interlinked today. Which also means that the future of socialism is as bleak or bright as that of humankind. . . .

IV

It was Engels‘ adjuration to followers to ‘not pick quotations from Marx or from him as if from sacred texts, but think as Marx would have thought in their place’. He had insisted that ‘it was only in that sense that the word Marxist had any raison d’etre’. . . .

Accordingly, I would make a few concluding observations on the question of socialism today, again with the help of passages culled from my Crisis of Socialism — Notes in Defence of a Commitment, which carries a detailed discussion of the issues now being touched upon.

Socialism arose in opposition to capitalism with the rise of modern capitalism itself. Marx’s many-sided critique of capitalism soon provide it with a scientific theoretical basis, establishing it as socialism of our times, distinguishing it from its various other forms — some of which (Reactionary Socialism, Petty-bourgeois Socialism, German or ‘True’ Socialism, Conservative or Bourgeois Socialism, Critical Utopian Socialism, etc.) Marx himself noted in the Communist Manifesto — forms in which it keeps reappearing from time to time. In other words, socialism came up long before Soviet Union did, and we are socialist because of capitalism and not because of Soviet Union. Some of us were in fact socialist despite Soviet Union. And socialism remains on the agenda of history so long as capitalism lasts.

For Marx socialism is essentially a negation of capitalism, a negation of its economy, politics and ethical-aesthetic values, its multiple alienations and commodification of life. There are no blueprints of socialist society of the future in Marx’s social theory. His scientific method forbidding any such speculation, Marx simply refused to ‘compose the music of the future’. He visualised the construction of socialism, or communist society proper, as constituting a long period of transition. But the problems of this transition were never seriously discussed or theorised by Marx.

There are only scattered references to it in different writings of Marx and Engels, concerned primarily with characteristics of socialism as a transitional society between capitalism and communism (which they regarded as the goal towards which history was moving). The most important single document of classical Marxism here, that is, on the subject of construction of a new socialist society, is Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Programme — really Marx’s marginal notes to the programme of the German Workers Party, published by Engels after Marx’s death, sixteen years after Marx wrote them. The very title is significant. The only time Marx is drawn into making somewhat detailed, yet all too brief, comment on the subject, it is as a critique of his own party or followers in Germany for their confused and shoddy thinking over several issues, which also included that concerning the socialist society of the future — a critique distinguished for ‘the ruthless severity’ and ‘mercilessness’ typical of Marx in matters of theory. To be specifically noted here is that Marx never saw socialism, ‘advanced’, ‘developed’, or any other, as a social formation existing in its own right (as Soviet Marxism did); that would be plainly violative of its essential character as Marx defined it, that is a transition between capitalism and communism. As was common in his times, there is a certain loose usage of the term ‘socialism’ in Karl Marx. Quite often he used ‘socialism’ and ‘communism’ as synonymous terms, both referring to the same kind of society, that is, a ‘cooperative society’ or ‘association’ based on ‘free associated labour’. More specifically, it is what Marx called ‘the first phase of communist society’ which later Marxists, including Lenin, came to describe as ‘socialism’ (as opposed to ‘communism’ proper). Marx, therefore, nowhere speaks of ‘socialism’ as a distinct stage or social formation or of ‘transition between socialism and communism’. For Marx, as the new society emerges from the capitalist society itself, the former is obviously an integral part of the same new society, being its ‘first phase’ only chronologically, with the specific kind of developments corresponding to it. For him between capitalism and communism lies no stage or stages, only a transition, more or less prolonged according to circumstances, possibly a whole epoch or perhaps even more than one historical epoch. Lenin, though sharing the loose usage often equated socialism with communism, was equally explicit in speaking of ‘transition period between capitalism and communism’. . . .

I would suggest that Marx’s view here is theoretically correct and politically more fruitful as against positing the transition in terms of stages such as ‘new democracy’, ‘people’s democracy’, ‘revolutionary democracy’, ‘socialist society’, etc.

That there is no foreordained model or blueprint of socialism or socialist transition, certainly none suitable for all countries and all times, does not mean absence of general principles that flow from the Marxist tradition, the experience gained in national liberation and social revolutionary struggles and the efforts at socialist construction so far. For this reason critical understanding of Marxist tradition and revolutionary struggles of the past, and an equally critical analysis of and drawing of lessons from the past experiments in socialism, even when they have failed, is more than an intellectual game; it is an urgent and practical necessity for socialists everywhere, including those in the Third World, seeking a proper perspective on possible socialist transition in their countries. . . .

Socialism, for Marx, is not merely a set of humane economic arrangements; it is an emancipatory project. Marx saw socialism in its transition to communism as humankind’s transition to ‘the realm of freedom’ which according to him lies beyond material pursuits, beyond all activity geared to economic needs. He wrote:

. . . The realm of freedom actually begins only where labour which is determined by necessity and mundane considerations ceases; thus in the very nature of things it lies beyond the sphere of actual material production. Just as the savage must wrestle with nature to satisfy his wants, to maintain and reproduce life, so must civilised man, and he must do so in all social formations and under all modes of production. . . . Freedom in this field can only consist in socialised man, the associated producers, rationally regulating their interchange with nature, bringing it under their common control, instead of being ruled by it as by a blind power; and achieving this with the least expenditure of energy and under conditions most favourable to, and worthy of, their human nature. But it nonetheless still remains a realm of necessity. Beyond it begins that development of human power which is an end in itself, the true realm of freedom, which, however, can blossom forth only with this realm of necessity as its basis.

The aspirations or vision that Marx here sets forth is in fact as old as civilisation; it is there, for instance, in Plato and Aristotle, though its realisation, then and afterwards, was seen possible only for a few. Marx put more substance into this aspiration and sought its realisation for all human beings. In other words, economic activity was, throughout, deemed to have meaning only if it serves something other than itself. For Marx this is activities ‘valued as an end in themselves’ (as he phrased it in the Grundrisse), which for him is indeed ‘the true measure of wealth’. . . .

Marx, in line with his mode of thinking, took a historical view of the growth of needs and desires of human beings as one aspect of the general development of human nature, which is also the subjective aspect of the growth of human powers and capacities. His argument is suggestive of an infinite future of creation and cultivation of ‘the wealth of subjective human sensitivity,’ of specifically human senses, which is really the same as human nature all the time becoming more human. And the important point is that, for Marx, the exercise of these naturally and historically produced specifically human senses — the sense for music and poetry, art, science and history, love, justice and compassion, and so on — constituted the very essence of a truly human appropriation of life and nature, a genuinely rich human life. That is how in pointing out the alienating, depersonalising and dehumanising consequences of capitalism, Marx particularly focused attention on the fact that for all the glorious human senses, whose active and concrete exercise alone constitutes the true content of a genuinely rich human life, capitalism substitutes a single abstract sense, the sense for property, a particular, historically transient, substitute sense which plays havoc with human personality and plunges man, in the words of Ladislav Stoll, ‘into the terrible inner sickness of a dehumanised world’. Marx wrote: ‘In place of all these physical and mental senses there has . . . come the sheer estrangement of all these senses — the sense of having. The human being had to be reduced to this absolute poverty in order that he might yield his inner wealth to the outer world’. ‘The more you have‘, said Marx, ‘the less you are‘. Hence his insistence that ‘the transcendence of private property is therefore the complete emancipation of all human senses and attributes’. He spoke of communism, ‘the actual phase necessary for the next stage of historical development in the process of human emancipation and recovery’, ‘as the positive transcendence of private property as human self-estrangement, and therefore as the real appropriation of the human essence by and for man; communism therefore as the complete return of man to himself as a social (i.e., human) being — a return become conscious, and accomplished within the entire wealth of previous development.’ Marx added: ‘What is to be avoided above all is the re-establishing of “Society” as an abstraction vis-à-vis the individual. The individual is the social being. His life . . . is therefore an expression and confirmation of social life.’ Marx is an individualist in the basic sense that his ultimate vision was a society where every individual could be a fully human being, where, as Marx himself put it, ‘the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all’. . . .

Such is the fulfillment Marx’s socialism/communism seeks for humankind. As Engels expressed it, ‘it is humanity’s leap from the realm of necessity into the realm of freedom’, the end of its ‘pre-history’ and beginning of ‘truly human history’.

For Marx socialism is nothing inevitable, it is something to be struggled for.

Marx was no determinism, ever. Whatever determinism there is in his Marxism is a most conditional one, which accords primacy to human praxis, to revolutionary politics. If attention was drawn to the economic-structural necessities underlying the historical processes, it was for enhancing the freedom for praxis, for not foreclosing but liberating human practice, for freer choices by humans, free not in some abstract or metaphysical sense, but in the only possible human sense of men and women choosing and acting with the fullest possible knowledge and consideration of the necessities of the objective material situation or circumstances. Such is the dialectics of freedom and necessity in Marx. . . .

Thus there are no inevitabilities in Marx and no guarantees of victory either; only alternatives. Even as he insisted in the Communist Manifesto that ‘the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle’, Marx had immediately added that this struggle ‘each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes’. Again, he had hailed the productive achievements of capitalism — ‘it has been the first to show what man’s activity can bring about’, creating ‘more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together ‘ (Communist Manifesto). But he had also pointed out not only the damage that capitalism regularly inflicts upon humans and nature but also its long-term destructive potential — ‘its accumulation process’, Marx wrote in Grundrisse, can have ‘the consequences even for the total destruction of humanity’ — a prognosis which Rosa Luxemburg later summed up as the alternative: ‘socialism or barbarism’.

Incidentally, these alternative to socialism — the threat of ‘common ruin of the contending classes’, and ‘the total destruction of humanity’ — are already a part of the reality of our world today.

For whatever reasons, which certainly included an underestimation of capitalism’s productive potential and resilience, Marx gave capitalism a short lease of life, which allowed for the possibility of realizing socialism as an emancipatory project, that is initiating the epochal transition this project implied. In his main theory on the subject, based on his view of the historical tendencies of advanced capitalist development in Europe, Marx visualized the necessity as well as the possibility of a transition from capitalism to socialism/communism in the countries of advanced industrial development, with their mature productive basis and proletarian presence — ‘Empirically, communism is only possible as the act of the dominant peoples “all at once” and simultaneously, which presupposes the universal development of productive forces and the world intercourse bound up with them’, is how Marx put it in The German Ideology. Accordingly Marx looked forward to an early revolution in Europe — though he also recognized (in a letter to Engels in 1858): ‘For us the difficult question is this: the revolution on the Continent is imminent and its character will be at once socialist; will it not be necessarily crushed in this little corner of the world, since on a much larger terrain the development of bourgeois society is still in the ascendant’. The hoped-for European revolution finally arrived in the aftermath of the First World War but it survived only in Russia, confronting Lenin and his Bolsheviks with a totally unanticipated task: attempt a socialist transition in a single backward country, a situation or possibility that was never theorized by Marx. And now, though not inevitable, the attempt has failed. History seems to have played a trick on the doctrine of Karl Marx. This trick including the failure in the Soviet Union is eminently amenable to explanation in terms of this very doctrine, but more important is to note the consequent reality of the contemporary world in relation to Marx’s own perspective on socialism and the struggle for socialism in our times.

Of this reality three features need to be particularly noticed.

Firstly, as a capitalist world, it is a world of ‘overdeveloped’, ‘underdeveloped’ or so-called ‘developing’ countries. The latter two categories are generally well understood but we need to take a closer look at the ‘overdeveloped’ countries of advanced capitalism. For one, capitalism survives and is indeed dominant today, but as noticed earlier, it remains a failed system. Other considerations apart, capitalism has been a failure in terms of possibly the most legitimate criteria for assessing the performance of a social system: ‘fullness of employment’ and ‘goodness of employment’ of the actual and potential resources available in society. Never before in human history has the gap between society’s potentiality and society’s performance been so immense as it is today in capitalism’s current stage of development. Evidence is there, as we have already noticed, in the extraordinary productive capacity that three successive industrial revolutions have put at the disposal of humankind and the poverty and illiteracy, squalid slums and homelessness that are the lot of millions of families in the wealthiest countries of the capitalist world and the hunger and misery of hundreds of millions of people, living out their empty and barren lives in the hovels of the peripheral or semi-peripheral poor countries of the Third World. . . .

Capitalism continues to survive, but this, by itself, cannot be seen as an argument for the desirability, or a sign of the progressiveness of the capitalist order, much less as any sort of ‘triumph’ of capitalism. ‘That position’, says Paul Baran, ‘is no more defensible than would be the view that an inability of the human body to resist tuberculosis, however caused, furnishes a proof of the harmlessness or even usefulness of that illness’. . . .

He adds: ‘The failure of an irrationally organised society to generate internal forces pressing towards and resulting in its abolition and replacement by more rational, more humane social relations results necessarily in economic stagnation, cultural decay, and a widespread sense of despondency. Such a society — even if once the most advanced in the world — loses its position of leadership, slides into the backwaters of historical development, and turns into a breeding ground of reaction, inhumanity, and obscurantism.’ This is indeed the case today, not only in the United States but increasingly in the other so-called advanced societies of late capitalism. . . .

The U.S. leading, these societies are, in a profound sense, to a greater or lesser degree, sick societies. Concerned scholars have written of the phenomenon of ‘alienation’ in these societies, their citizens’ growing sense of anomie and estrangement, of isolation, hostility and frustration. They are sick with these and a hundred other social and psychic ailments born of prolonged living under an essentially irrational system, sick with apathy and boredom, with ‘other-directedness’ and conformism, with fears, insecurities and neuroses of all kinds. Their sustained social regression is reflected as much in the reaction and obscurantism they breed, their frivolous consumption and culture of drugs, and even guns, as in the debilitating barrage of fraudulent politics, barren culture and stupefying entertainment, inspirational rackets and demoralising press, and comic books, to which their people, even otherwise ill-educated, are exposed all the time. Societies in the grip of crises which they cannot resolve, they are inevitably producing deep pathological deformations which manifest themselves variously in different places as racism, sexism, anti-Semitism, xenophobia, ethnic or national hatreds, fundamentalism and intolerance, even as plain cruelty and aggression. Poverty, unemployment and insecurity-related crimes and associated phenomena — ill health and suicides, alcoholism and drug addiction, racist discrimination and criminal violence, violence against women and child abuse, etc. — are on the rise everywhere. In many of these ‘advanced’ societies marginal indigenous populations are rapidly being wiped out for one reason or another. By their very nature profoundly immoral societies, based as they are on domination and exploitation of man by man, along with humanistic values and culture and all human relationships, even their professed moralities and principles now stand devastated by the morality and values of ‘the market’. And, most significantly, there is the near-absence of ideals in these societies, of any concern for a better future to strive for, that has been the motive force of all human progress in the past. The instruments of communication and discovery invented by their technological genius have become the means of debasing people’s understanding and preventing them from looking beyond the capitalist horizon. . . .

Indeed, the sickness of these so-called advanced societies, the spiritual disarray of the capitalist civilisation they represent, is nowhere more evident than in their cynical idealisation of capitalism as it exists and utter lack of any vision of a secure and more satisfying life beyond their ‘consumerist heaven of instant gratification’, a life which would be satisfactory of basic human needs — decent livelihood, knowledge, solidarity, cooperation with fellow human beings, gratification in work and freedom from toil — and provide the possibility of men and women appropriating the world with all their glorious human senses. It needs to be added that these societies are all the more sick societies because they need to change the existing state of affairs but are unable to generate the necessary social forces for carrying out the revolutionary change they so badly need. . . .

The continuance of capitalism as ‘sick’ societies of advanced capitalist West has an important implication. In a sense socialism arrived a little before its time, attempted as it was first in Russia, a society that was not prepared to build it. The Bolsheviks had to contend with the problems of a backward, underdeveloped capitalist-feudal social order, problems which caused grave distortions and contributed to the ultimate failure of their attempt to build socialism. Those who may be called upon to build a late-arrived socialism in advanced capitalist countries will have to contend with equally difficult but different problems of an ‘overdeveloped’ capitalism — a capitalism living beyond its time as it were, beyond the period of its historical legitimacy. In other words, as with ‘underdevelopment’, ‘overdevelopment’, too, poses its own unanticipated problems for the realisation of Marx project of socialism.

Socialism, of course, remains on the agenda wherever capitalism exists, be it ‘overdeveloped’, ‘underdeveloped’, ‘developing’ or any other. And there is always the overarching question as to what kind of society we, as human beings, want to have. Surely it is people and not ‘economic growth’ or productivity that must come first in such a society. It has to be a humane society that fosters cooperation, solidarity and respect for universal ethical values, and makes for a non-alienated, ‘truly rich human life’ that Marx spoke of. Of course such a society is impossible without basic material security and need satisfaction. But to believe that you can assure need satisfaction through greed, private acquisitive drives, universal competition and strife — the values of capitalism — and yet hope for a humane society of cooperation and solidarity is utopianism of the worst kind. Subordinating humanity to economics, to imperatives of the market, capitalism commodifies life and undermines and rots away the relations between human beings which constitute societies. Its ethos of the market place — competition, egoism, aggression, alienation, universal venality, in short the rat race — creates a moral vacuum in which nothing counts except what the individual wants and can grab, here and now. At the end of it all, even when wants are satisfied, the people are ever more subordinated, ever less free, ever more flattened and made passive by the dictatorship of consumerism, that arbitrarily shapes values, imposing on them the heavy burden of uniformity. The values of difference, individualisation (not individualism), all-sided development of man, of human freedom itself, disappear in the market place which is proclaimed to be free. As human beings, people simply don’t fit into capitalism, which is a quintessential market society. For a truly humane society to come into existence, capitalism has to go. . . .

But, in view of their ‘overdeveloped’, ‘underdeveloped’ or ‘developing’ character, to speak of socialism in relation to these capitalist societies is not to posit socialism as achievable today or tomorrow, or even the day after, but to posit it as people’s alternative strategic goal, as the principle governing people’s politics which links together their immediate, ongoing and emerging struggles in an ultimate project of revolutionary transformation of society, as the goal of a long transitional process whose specifics and speed will depend on the objective material conditions and the nature and balance of class forces involved at each stage of the struggle. . . .

In other words, while expressions like ‘building socialism’ or ‘building socialism of the 21st century’ have a certain historical and political legitimacy, what is on the agenda is a socialism-oriented development, such that, no matter how slow or halting or contradictions-laden, it is a development away from capitalism and the imperatives of its market and towards Marx’s emancipatory vision of socialism, which, in any case, was visualised as a transition spanning an entire epoch, even more than one epoch.

This, again, is not to suggest any ‘model’ of socialist politics. Just as there is no single or foreordained model of socialism, one that is suitable for all climes and all times, there is none of socialist politics either. The specific conditions or demands and the forms of struggle they generate will vary from country to country. Which, however, does not mean the absence of general principles to guide it that flow from the Marxist tradition and the experience gained in social revolutionary and national liberation struggles. The recovery of these principles is in fact a must for any successful pursuit of socialist politics today. . . .

Secondly, since global capitalism is nationally organised and immediately dependent on national states, national economies and national states remain the primary terrain of anti-capitalist organisation and struggle. Of course an international perspective, working people’s solidarity across national frontiers, remains vital to any socialist movement. And today there exists a focus for such solidarity as has, perhaps, never before existed in the history of capitalism. The universalisation of capitalism has not brought about the cessation but instead the universalisation of struggle against capitalism. When, with globalisation, just about every state is following the same destructive logic, domestic struggles against that common logic can be the basis — in fact the strongest possible basis — of a new internationalism. But looking for that internationalism must not be an excuse for giving up on local national struggles. The main arenas of struggle against global capitalism still remain local and national. ‘Workers of all countries, unite’ remains the motto but this ‘unity’ obviously begins at home. There is a growing space for common transnational struggles, but the established order has still to be primarily fought on our own home pitch. As the Manifesto put it a long time ago: ‘the proletariat of each country must, of course, first of all settle matters with its own bourgeoisie.’ If the historical experience of more than a century since the Paris Commune is any guide this is exactly how it has been. The world revolutionary process has turned out to be extremely uneven and has moved from country to country. . . .

In other words, the nation state is indeed the concrete terrain on which the struggle for the radical transformation of society must begin and may have to be carried forward. It may be added that to argue that a nation state — and this includes states of the size and resources of Britain, France or Italy, or for that matter, India, China or Russia — cannot provide the ground on which the radical transformation of society can be attempted is to rule out such a transition for the forthcoming historical period. It is to abdicate the struggle for socialism in our time. . . .

Thirdly, it was Marx’s prognosis that capitalism in its ultimate consequences could spell even ‘the total destruction of humanity’. But, giving capitalism a short lease of life, Marx never explored this distant possibility. The distant possibility is now an imminent threat hanging over the future of humankind. As noted earlier, Rosa Luxemburg had summed up Marx’s prognosis in her famous poser: ‘socialism or barbarism’. Capitalism living beyond its historical time indeed spells a future of barbarism for humankind. It could be a nuclear holocaust that its politics has threatened for more than half a century or the almost certain ecological disaster which — noise over so-called ‘sustainable development’ notwithstanding — capitalism’s accumulative logic now portends. This makes the struggle for socialism all the more imperative and urgent today.

It can be legitimately argued, without any underestimation of the prospects of socialist renewal in the advanced capitalist West or the erstwhile ‘socialist world’, that it is the countries of the Third World which are likely to be the storm centres of such struggle, keeping socialism still on the agenda for the future of humankind. For the simple reason that they have no other choice, the common people there have no future otherwise. For the same reasons as in the past, the world revolutionary process is more likely to proceed through the backward, ‘less developed’ or ‘developing’ countries of the periphery and semi-periphery of the world capitalist system. . . .

Therefore, a couple of additional observations on the question of struggle for socialism in these countries will not be out of place.

As a result of the unequal development in capitalist expansion, for causes that are neither local nor conjunctural but systemic and structural to capitalism as a world system, socialist revolutions or revolutionary movements of our time have appeared most often not at the centre but at the periphery of world capitalism — in Russia, China, Cuba, Indochina, or in the name of socialism, in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. For this is indeed where the worst victims of global capitalism’s irrationality and exploitation are to be found, and therefore from where the challenge to capitalism emanated. The collapse of the Soviet Union does not end or modify the structural logic of global capitalism as manifested in poverty, underdevelopment, deindustrialisation and exploitation in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. It has only made global capitalism all the more powerful and given a new edge to its predatory logic. Any social system built on inequality in the command of human and natural resources works in many ways to reproduce itself and to increase the extent of the in-built inequality. So does capitalism. But as a market-governed system capitalism carries this process to the extremes. The law of accumulation of capital inexorably produces, reproduces, and enhances inequality — wealth at one end and poverty at the other, not only within countries but on a world scale. And this is precisely what globalisation — another of the currently fashionable, reality-obscuring buzz words — does. It has only sharpened the global capitalism’s contradiction between its developed centre and exploited periphery. But this, if past is any guide, also makes this periphery, the Third World of the worst victims of contemporary capitalism, the site of revolts, of new countrywise challenges to the global capitalist order, of the resumed struggle for socialism. . . .

This, as mentioned earlier, is not to posit socialism as achievable today or tomorrow, or even the day after, but to posit it as people’s alternative strategic goal, as the principle governing people’s politics which links together their immediate, ongoing and emerging struggles in an ultimate project of revolutionary transformation of society, as the goal of a long transitional process whose specifics and speed will depend on the objective material conditions and the nature and balance of class forces involved at each stage of the struggle for the socialist goal. Immediately it means saying ‘no’ to globalisation, a ‘delinking’ from the global capitalist market — which however does not mean any kind of ‘autarky’ — and opting for a pro-people socialism-oriented autonomous development, one governed not by external imperatives, those flowing from the requirements of the world capitalist market (export-led growth, etc.) and the associated consumerism of the rich, but primarily by internal imperatives, those flowing from an assessment of country’s own resources and the needs of its people. Development which can meet the material needs of the people in the Third World is impossible within the framework of capitalism, national or globalised. Socialism has to be the strategic goal, whatever be the long or short transitional route to it. Historical experience allows no other choice. . . .

Any attempt at saying ‘no’ to globalisation or ‘delinking’ is likely to exact a heavy price in many ways, including an unavoidable trade-off between the requirements of productivity and those of minimising the polarising impact of global capitalism’s enormous economic power. But once ‘productivism’ is abandoned and human welfare has the priority, this need not be a deterrent to adopting the strategy that ‘delinking’ involves. The details of economic policies in pursuit of this strategy will obviously vary from country to country. Here only a few broadly suggestive observations can be made. . . .

This strategy postulates a revolutionary state, representative of a popular front of workers and peasants, undertaking at the very outset a comprehensive programme of eradication of mass poverty, universal primary education, health care, housing, and provision of basic necessities for all. Initiating steps towards redistribution of incomes and development of backward areas will be a priority for state’s active intervention in the economy which, even as it covers such areas as foreign relations, production and social distribution, research and training, and the like, will need to secure an effective transitional combination of planning and market forces without letting the market or its values take over. Agrarian revolution benefiting the rural proletariat and small farmers, thereby improving the productive capacity in the rural areas, and laying the basis of cooperative effort and voluntary collectivisation of agriculture should be high on its agenda of economic reconstruction, as should be the transformation of the informal sector into a popularly managed transitional economy. A building up or restructuring of industry is obviously necessary. But it can neither be one based on ‘international competitiveness’ (that is promoting exports through low costs of local labour) nor on ‘import substitution’ (promoting production for the consumption of the privileged local classes). Not that all effort in these directions is ruled out; some of it may even be necessary. Only priorities, for years to come, lie elsewhere. The important thing is to develop and organise productive forces in a manner that helps the rural sector leap forward, carries industrialisation to the countryside and in general ensures a pattern of growth which, refusing the wasteful production to satisfy elite consumerism, immediately benefits the popular masses, satisfying their basic needs, needs created and satisfiable by the redistribution of income. It should be obvious that the overall development of a Third World country today cannot support the First World consumption levels of its elites. What is needed is a diversification and development of internal markets for domestic goods and services governed by the overall principle that, beyond a certain necessary priority charges of an unequal nature, private needs and wants should be satisfied (and this goes for their increasing satisfaction) only at a level at which they can be satisfied for all, and beyond this all increase in the production of consumer goods should be for collective consumption. . . .

Such a socialism-oriented pro-people endogenous development process will draw on each nation’s own strengths and domestic resources and capacities, including those of the hardworking poor who yet remain the most creative and productive force in society. It will give the common people, overwhelming mass of workers and peasants, a positive stake in the economy and mobilise them for building a better society as well as for the inevitable struggle against global imperialism and its local allies or partners — an awakened and aroused people are indeed the best defence even against armed aggression. Needless to add, such popular mobilisation and struggle will be all the time necessary to carry through the strategic option that socialism-oriented delinking involves. . . .

What the above strategy in effect demands is that not economics but politics, that is class politics, be put in command of the economy. ‘Politics in command’ means posing such questions as: growth? but which growth? for what purpose? for whose sake, whose benefit or profit? for what kind of society and within which environment? These are questions which are central to any search for a real alternative to capitalism, vital for the very survival of socialist movement today. They are all the more vital to pose in the Third World suffering the worst ravages of capitalism. We must ask: is our goal meeting ‘the needs of the economy’, its ‘anonymous masters’ as they have been called — ‘abstractions such as financial markets, interest rates, exchange rates, commodity prices, indexes and statistical artefacts of all kinds’ — or satisfaction of the needs of the people, allowing citizens the possibility of living as human beings? Is the starting point of our economic exercises to be calculation of deficits in order to cut them at the cost of the people or a determination of resources needed to satisfy people’s needs in order to find or raise them? And our language? Do we practice the obscurantism of GDP, fiscal and revenue deficits, balance of payments, growth rates etc., etc. or speak more humanely in terms of such things as food and clean drinking water, health care and sanitation, housing and education, etc. so that economy becomes a transparent and accountable means of integrating these basic human needs of the people with a planned use of domestic resources, a use which also takes care of questions of equality, social justice including gender justice, employment, ecologically sustainable development, etc.? . . .

Economic and technological backwardness is often pressed as an argument to counter the plea for such autonomous economic development. (Getting access to the most modern technology is another usual argument for the need to actively participate in world trade). This calls for two very brief observations. In the first place it is useful to recognise that if, despite economic backwardness, the priority is given to the needs of the poorest and most deprived sections of the people, there is much that can be done at the outset even in absence of growth of productive forces. The redistribution of wealth and the use of idle or underutilised human and material resources, their more productive deployment, can bring quick improvement in health, education and general living conditions of large masses of people. Early years of post-revolutionary societies in the Soviet Union and elsewhere provide ample evidence of this achievement which could be the basis for further development along socialist lines.

In the second place once we overcome the fetishism of science and technology — which attributes to them properties or power they do not possess, and at times even expects them to do the job of a social revolution which they simply cannot — and, as with economic development so with technology, ask the basic question: ‘technology for what purpose?’, the argument for getting access to the most modern Western technology via globalisation — even if that was certain which it most certainly is not — loses much of its force. If the purpose is to satisfy the consumerist hunger of the privileged part of the population and therefore supply it with the most modern gadgets, designs, and goodies of the West, then rushing into globalisation is indeed understandable. But if the purpose or priority is to meet the needs of all the people for decent food, clothing and shelter, clean water, proper sanitation and health protection, education and cultural opportunities and the like, then devoting scarce resources to the most modern technology will be only wasteful because there is little in the latest technology of the West that would make a significant contribution. In fact what is most useful and relevant in technology, Western or otherwise, for improving the way of life of the masses is widely known. Most of this technology is already available at home and what else is needed is obtainable in the normal course of managed trade. . . .

My observations so far are directly or indirectly relevant to the struggle for socialism in India. But, exemplified by the crisis of CPM politics in West Bengal, the issue of this struggle has also come up, in a sui generis form, at the level of state politics in India which calls for a brief discussion in its own right.

Our struggle for freedom was a struggle to break out of a globalization whose structural logic meant wealth in England and poverty in India. This was a necessary, though not sufficient, condition to be able to build a better life for our people. Aware of this exploitative logic of the global capitalist market, of centuries of experience of imperialism which provides little evidence of the beneficial effect of foreign investment in countries of the Third World so far as the common people are concerned, and in its own way influenced by the interim successes of the Soviet Union, the post-independence (Nehruvian) national project opted for the strategic goal of a state-led self-reliant development promising economic growth with ‘equity and distributive justice’ to the people. For understandable reasons, it did not work out as Nehru had intended. There was a degree of economic growth but not much equity or distributive justice for the people, and the project ended up building an India-specific government-supported Third-Worldist capitalism. The rhetoric of ‘socialistic pattern of society’ only deceived the people, legitimized the statist capitalism that was coming up and created confusion about it as ‘socialism’ so that when, passing through a series of economic and political crises mid-sixties onward, the project finally collapsed in 1991, it was, and continues to be, misinterpreted as the failure of socialism in India.