On Monday, May 12, 2008, at 10:00 a.m., in an operation involving some 900 agents, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) executed a raid of Agriprocessors Inc, the nation’s largest kosher slaughterhouse and meat packing plant located in the town of Postville, Iowa. The raid — officials boasted — was “the largest single-site operation of its kind in American history.” At that same hour, 26 federally certified interpreters from all over the country were en route to the small neighboring city of Waterloo, Iowa, having no idea what their mission was about. The investigation had started more than a year earlier. Raid preparations had begun in December. The Clerk’s Office of the U.S. District Court had contracted the interpreters a month ahead, but was not at liberty to tell us the whole truth, lest the impending raid be compromised. The operation was led by ICE, which belongs to the executive branch, whereas the U.S. District Court, belonging to the judicial branch, had to formulate its own official reason for participating. Accordingly, the Court had to move for two weeks to a remote location as part of a “Continuity of Operation Exercise” in case they were ever disrupted by an emergency, which in Iowa is likely to be a tornado or flood. That is what we were told, but, frankly, I was not prepared for a disaster of such a different kind, one which was entirely man-made.

I arrived late that Monday night and missed the 8pm interpreters briefing. I was instructed by phone to meet at 7am in the hotel lobby and carpool to the National Cattle Congress (NCC) where we would begin our work. We arrived at the heavily guarded compound, went through security, and gathered inside the retro “Electric Park Ballroom” where a makeshift court had been set up. The Clerk of Court, who coordinated the interpreters, said: “Have you seen the news? There was an immigration raid yesterday at 10am. They have some 400 detainees here. We’ll be working late conducting initial appearances for the next few days.” He then gave us a cursory tour of the compound. The NCC is a 60-acre cattle fairground that had been transformed into a sort of concentration camp or detention center. Fenced in behind the ballroom/courtroom were 23 trailers from federal authorities, including two set up as sentencing courts; various Homeland Security buses and an “incident response” truck; scores of ICE agents and U.S. Marshals; and in the background two large buildings: a pavilion where agents and prosecutors had established a command center; and a gymnasium filled with tight rows of cots where some 300 male detainees were kept, the women being housed in county jails. Later the NCC board complained to the local newspaper that they had been “misled” by the government when they leased the grounds purportedly for Homeland Security training.

Echoing what I think was the general feeling, one of my fellow interpreters would later exclaim: “When I saw what it was really about, my heart sank. . . .” Then began the saddest procession I have ever witnessed, which the public would never see, because cameras were not allowed past the perimeter of the compound (only a few journalists came to court the following days, notepad in hand). Driven single-file in groups of 10, shackled at the wrists, waist and ankles, chains dragging as they shuffled through, the slaughterhouse workers were brought in for arraignment, sat and listened through headsets to the interpreted initial appearance, before marching out again to be bused to different county jails, only to make room for the next row of 10. They appeared to be uniformly no more than 5 ft. tall, mostly illiterate Guatemalan peasants with Mayan last names, some being relatives (various Tajtaj, Xicay, Sajché, Sologüí. . .), some in tears; others with faces of worry, fear, and embarrassment. They all spoke Spanish, a few rather laboriously. It dawned on me that, aside from their nationality, which was imposed on their people in the 19th century, they too were Native Americans, in shackles. They stood out in stark racial contrast with the rest of us as they started their slow penguin march across the makeshift court. “Sad spectacle” I heard a colleague say, reading my mind. They had all waived their right to be indicted by a grand jury and accepted instead an information or simple charging document by the U.S. Attorney, hoping to be quickly deported since they had families to support back home. But it was not to be. They were criminally charged with “aggravated identity theft” and “Social Security fraud” — charges they did not understand . . . and, frankly, neither could I. Everyone wondered how it would all play out.

We got off to a slow start that first day, because ICE’s barcode booking system malfunctioned, and the documents had to be manually sorted and processed with the help of the U.S. Attorney’s Office. Consequently, less than a third of the detainees were ready for arraignment that Tuesday. There were more than enough interpreters at that point, so we rotated in shifts of three interpreters per hearing. Court adjourned shortly after 4pm. However, the prosecution worked overnight, planning on a 7am to midnight court marathon the next day.

I was eager to get back to my hotel room to find out more about the case, since the day’s repetitive hearings afforded little information, and everyone there was mostly refraining from comment. There was frequent but sketchy news on local TV. A colleague had suggested The Des Moines Register. So I went to DesMoinesRegister.com and started reading all the 20+ articles, as they appeared each day, and the 57-page ICE Search Warrant Application. These were the vital statistics. Of Agriprocessors’ 968 current employees, about 75% were illegal immigrants. There were 697 arrest warrants, but late-shift workers had not arrived, so “only” 390 were arrested: 314 men and 76 women; 290 Guatemalans, 93 Mexicans, four Ukrainians, and three Israelis who were not seen in court. Some were released on humanitarian grounds: 56 mostly mothers with unattended children, a few with medical reasons, and 12 juveniles were temporarily released with ankle monitors or directly turned over for deportation. In all, 306 were held for prosecution. Only five of the 390 originally arrested had any kind of prior criminal record. There remained 307 outstanding warrants.

This was the immediate collateral damage. Postville, Iowa (pop. 2,273), where nearly half the people worked at Agriprocessors, had lost 1/3 of its population by Tuesday morning. Businesses were empty, amid looming concerns that if the plant closed it would become a ghost town. Beside those arrested, many had fled the town in fear. Several families had taken refuge at St. Bridget’s Catholic Church, terrified, sleeping on pews and refusing to leave for days. Volunteers from the community served food and organized activities for the children. At the local high school, only three of the 15 Latino students came back on Tuesday, while at the elementary and middle school, 120 of the 363 children were absent. In the following days the principal went around town on the school bus and gathered 70 students after convincing the parents to let them come back to school; 50 remained unaccounted for. Some American parents complained that their children were traumatized by the sudden disappearance of so many of their school friends. The principal reported the same reaction in the classrooms, saying that for the children it was as if ten of their classmates had suddenly died. Counselors were brought in. American children were having nightmares that their parents too were being taken away. The superintendant said the school district’s future was unclear: “This literally blew our town away.” In some cases both parents were picked up and small children were left behind for up to 72 hours. Typically, the mother would be released “on humanitarian grounds” with an ankle GPS monitor, pending prosecution and deportation, while the husband took first turn in serving his prison sentence. Meanwhile the mother would have no income and could not work to provide for her children. Some of the children were born in the U.S. and are American citizens. Sometimes one parent was a deportable alien while the other was not. “Hundreds of families were torn apart by this raid,” said a Catholic nun. “The humanitarian impact of this raid is obvious to anyone in Postville. The economic impact will soon be evident.”

But this was only the surface damage. Alongside the many courageous actions and expressions of humanitarian concern in the true American spirit, the news blogs were filled with snide remarks of racial prejudice and bigotry, poorly disguised beneath an empty rhetoric of misguided patriotism, not to mention the insults to anyone who publicly showed compassion, safely hurled from behind a cowardly online nickname. One could feel the moral fabric of society coming apart beneath it all.

The more I found out, the more I felt blindsighted into an assignment of which I wanted no part. Even though I understood the rationale for all the secrecy, I also knew that a contract interpreter has the right to refuse a job which conflicts with his moral intuitions. But I had been deprived of that opportunity. Now I was already there, far from home, and holding a half-spent $1,800 plane ticket. So I faced a frustrating dilemma. I seriously considered withdrawing from the assignment for the first time in my 23 years as a federally certified interpreter, citing conflict of interest. In fact, I have both an ethical and contractual obligation to withdraw if a conflict of interest exists which compromises my neutrality. Appended to my contract are the Standards for Performance and Professional Responsibility for Contract Court Interpreters in the Federal Courts, where it states: “Interpreters shall disclose any real or perceived conflict of interest . . . and shall not serve in any matter in which they have a conflict of interest.” The question was did I have one. Well, at that point there was not enough evidence to make that determination. After all, these are illegal aliens and should be deported — no argument there, and hence no conflict. But should they be criminalized and imprisoned? Well, if they committed a crime and were fairly adjudicated. . . . But all that remained to be seen. In any case, none of it would shake my impartiality or prevent me from faithfully discharging my duties. In all my years as a court interpreter, I have taken front row seat in countless criminal cases ranging from rape, capital murder and mayhem, to terrorism, narcotics and human trafficking. I am not the impressionable kind. Moreover, as a professor of interpreting, I have confronted my students with every possible conflict scenario, or so I thought. The truth is that nothing could have prepared me for the prospect of helping our government put hundreds of innocent people in jail. In my ignorance and disbelief, I reluctantly decided to stay the course and see what happened next.

Wednesday, May 14, our second day in court, was to be a long one. The interpreters were divided into two shifts, 8am to 3pm and 3pm to 10pm. I chose the latter. Through the day, the procession continued, ten by ten, hour after hour, the same charges, the same recitation from the magistrates, the same faces, chains and shackles, on the defendants. There was little to remind us that they were actually 306 individuals, except that occasionally, as though to break the monotony, one would dare to speak for the others and beg to be deported quickly so that they could feed their families back home. One who turned out to be a minor was bound over for deportation. The rest would be prosecuted. Later in the day three groups of women were brought, shackled in the same manner. One of them, whose husband was also arrested, was released to care for her children, ages two and five, uncertain of their whereabouts. Several men and women were weeping, but two women were particularly grief stricken. One of them was sobbing and would repeatedly struggle to bring a sleeve to her nose, but her wrists shackled around her waist simply would not reach; so she just dripped until she was taken away with the rest. The other one, a Ukrainian woman, was held and arraigned separately when a Russian telephonic interpreter came on. She spoke softly into a cellular phone, while the interpreter told her story in English over the speakerphone. Her young daughter, gravely ill, had lost her hair and was too weak to walk. She had taken her to Moscow and Kiev but to no avail. She was told her child needed an operation or would soon die. She had come to America to work and raise the money to save her daughter back in Ukraine. In every instance, detainees who cried did so for their children, never for themselves.

The next day we started early, at 6:45am. We were told that we had to finish the hearings by 10am. Thus far the work had oddly resembled a judicial assembly line where the meat packers were mass processed. But things were about to get a lot more personal as we prepared to interpret for individual attorney-client conferences. In those first three days, interpreters had been pairing up with defense attorneys to help interview their clients. Each of the 18 court appointed attorneys represented 17 defendants on average. By now, the clients had been sent to several state and county prisons throughout eastern Iowa, so we had to interview them in jail. The attorney with whom I was working had clients in Des Moines and wanted to be there first thing in the morning. So a colleague and I drove the 2.5 hours that evening and stayed overnight in a hotel outside the city. We met the attorney in jail Friday morning, but the clients had not been accepted there and had been sent instead to a state penitentiary in Newton, another 45-minute drive. While we waited to be admitted, the attorney pointed out the reason why the prosecution wanted to finish arraignments by 10am Thursday: according to the writ of habeas corpus they had 72 hours from Monday’s raid to charge the prisoners or release them for deportation (only a handful would be so lucky). The right of habeas corpus, but of course! It dawned on me that we were paid overtime, adding hours to the day, in a mad rush to abridge habeas corpus, only to help put more workers in jail. Now I really felt bad. But it would soon get worse. I was about to bear the brunt of my conflict of interest.

It came with my first jail interview. The purpose was for the attorney to explain the uniform Plea Agreement that the government was offering. The explanation, which we repeated over and over to each client, went like this. There are three possibilities. If you plead guilty to the charge of “knowingly using a false Social Security number,” the government will withdraw the heavier charge of “aggravated identity theft,” and you will serve 5 months in jail, be deported without a hearing, and placed on supervised release for 3 years. If you plead not guilty, you could wait in jail 6 to 8 months for a trial (without right of bail since you are on an immigration detainer). Even if you win at trial, you will still be deported, and could end up waiting longer in jail than if you just pled guilty. You would also risk losing at trial and receiving a 2-year minimum sentence, before being deported. Some clients understood their “options” better than others.

That first interview, though, took three hours. The client, a Guatemalan peasant afraid for his family, spent most of that time weeping at our table, in a corner of the crowded jailhouse visiting room. How did he come here from Guatemala? “I walked.” What? “I walked for a month and ten days until I crossed the river.” We understood immediately how desperate his family’s situation was. He crossed alone, met other immigrants, and hitched a truck ride to Dallas, then Postville, where he heard there was sure work. He slept in an apartment hallway with other immigrants until employed. He had scarcely been working a couple of months when he was arrested. Maybe he was lucky: another man who began that Monday had only been working for 20 minutes. “I just wanted to work a year or two, save, and then go back to my family, but it was not to be.” His case and that of a million others could simply be solved by a temporary work permit as part of our much overdue immigration reform. “The Good Lord knows I was just working and not doing anyone any harm.” This man, like many others, was in fact not guilty. “Knowingly” and “intent” are necessary elements of the charges, but most of the clients we interviewed did not even know what a Social Security number was or what purpose it served. This worker simply had the papers filled out for him at the plant, since he could not read or write Spanish, let alone English. But the lawyer still had to advise him that pleading guilty was in his best interest. He was unable to make a decision. “You all do and undo,” he said. “So you can do whatever you want with me.” To him we were part of the system keeping him from being deported back to his country, where his children, wife, mother, and sister depended on him. He was their sole support and did not know how they were going to make it with him in jail for 5 months. None of the “options” really mattered to him. Caught between despair and hopelessness, he just wept. He had failed his family, and was devastated. I went for some napkins, but he refused them. I offered him a cup of soda, which he superstitiously declined, saying it could be “poisoned.” His Native American spirit was broken and he could no longer think. He stared for a while at the signature page pretending to read it, although I knew he was actually praying for guidance and protection. Before he signed with a scribble, he said: “God knows you are just doing your job to support your families, and that job is to keep me from supporting mine.” There was my conflict of interest, well put by a weeping, illiterate man.

We worked that day for as long as our emotional fortitude allowed, and we had to come back to a full day on Sunday to interview the rest of the clients. Many of the Guatemalans had the same predicament. One of them, a 19-year-old, worried that his parents were too old to work, and that he was the only support for his family back home. We will never know how many of the 293 Guatemalans had legitimate asylum claims for fear of persecution, back in a country stigmatized by the worst human rights situation in the hemisphere, a by-product of the US-backed Contra wars of 1980s’ Central America under the old domino theory. For three decades, anti-insurgent government death squads have ravaged the countryside, killing tens of thousands and displacing almost two million peasants. Even as we proceeded with the hearings during those two weeks in May, news coming out of Guatemala reported farm workers being assassinated for complaining publicly about their working conditions. Not only have we ignored the many root causes of illegal immigration, we also will never know which of these deportations will turn out to be a death sentence, or how many of these displaced workers are last survivors with no family or village to return to.

Another client, a young Mexican, had an altogether different case. He had worked at the plant for ten years and had two American born daughters, a 2-year-old and a newborn. He had a good case with Immigration for an adjustment of status which would allow him to stay. But if he took the Plea Agreement, he would lose that chance and face deportation as a felon convicted of a crime of “moral turpitude.” On the other hand, if he pled “not guilty” he had to wait several months in jail for trial, and risk getting a 2-year sentence. After an agonizing decision, he concluded that he had to take the 5-month deal and deportation, because as he put it, “I cannot be away from my children for so long.” His case was complicated; it needed research in immigration law, a change in the Plea Agreement, and, above all, more time. There were other similar cases in court that week. I remember reading that immigration lawyers were alarmed that the detainees were being rushed into a plea without adequate consultation on the immigration consequences. Even the criminal defense attorneys had limited opportunity to meet with clients: in jail there were limited visiting hours and days; at the compound there was little time before and after hearings, and little privacy due to the constant presence of agents. There were 17 cases for each attorney, and the Plea offer was only good for 7 days. In addition, criminal attorneys are not familiar with immigration work and vice versa, but had to make do since immigration lawyers were denied access to these criminal proceedings.

In addition, the prosecutors would not accept any changes to the Plea Agreement. In fact, some lawyers, seeing that many of their clients were not guilty, requested an Alford plea, whereby defendants can plead guilty in order to accept the prosecution’s offer, but without having to lie under oath and admit to something they did not do. That would not change the 5-month sentence, but at least it preserves the person’s integrity and dignity. The proposal was rejected. Of course, if they allowed Alford pleas to go on public record, the incongruence of the charges would be exposed and find its way into the media. Officially, the ICE prosecutors said the Plea Agreement was directed from the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C., that they were not authorized to change it locally, and that the DOJ would not make any case by case exceptions when a large number of defendants are being “fast-tracked.” Presumably if you gave different terms to one individual, the others will want the same. This position, however, laid bare one of the critical problems with this new practice of “fast-tracking.” Even real criminals have the right of severance: when co-defendants have different degrees of responsibility, there is an inherent conflict of interest, and they can ask to be prosecuted separately as different cases, each with a different attorney. In fast-tracking, however, the right of severance is circumvented because each defendant already has a different case number on paper, only that they are processed together, 10 cases at a time. At this point, it is worth remembering also that even real criminals have an 8th Amendment right to reasonable bail, but not illegal workers, because their immigration detainer makes bail a moot issue. We had already circumvented habeas corpus by doubling the court’s business hours. What about the 6th Amendment right to a “speedy trial”? In many states “speedy” means 90 days, but in federal law it is vaguely defined, potentially exceeding the recommended sentence, given the backlog of real cases. This served as another loophole to force a guilty plea. Many of these workers were sole earners begging to be deported, desperate to feed their families, for whom every day counted. “If you want to see your children or don’t want your family to starve, sign here” — that is what their deal amounted to. Their Plea Agreement was coerced.

We began week two Monday, May 19th. Those interpreters who left after the first week were spared the sentencing hearings that went on through Thursday. Those who came in fresh the second week were spared the jail visits over the weekend. Those of us who stayed both weeks came back from the different jails burdened by a close personal contact that judges and prosecutors do not get to experience: each individual tragedy multiplied by 306 cases. One of my colleagues began the day by saying “I feel a tremendous solidarity with these people.” Had we lost our impartiality? Not at all: that was our impartial and probably unanimous judgment. We had seen attorneys hold back tears and weep alongside their clients. We would see judges, prosecutors, clerks, and marshals do their duty, sometimes with a heavy heart, sometimes at least with mixed feelings, but always with a particular solemnity not accorded to the common criminals we all are used to encountering in the judicial system. Everyone was extremely professional and outwardly appreciative of the interpreters. We developed among ourselves and with the clerks, with whom we worked closely, a camaraderie and good humor that kept us going. Still, that Monday morning I felt downtrodden by the sheer magnitude of the events. Unexpectedly, a sentencing hearing lifted my spirits.

I decided to do sentences on Trailer 2 with a judge I knew from real criminal trials in Iowa. The defendants were brought in 5 at a time, because there was not enough room for 10. The judge verified that they still wanted to plead guilty, and asked counsel to confirm their Plea Agreement. The defense attorney said that he had expected a much lower sentence, but that he was forced to accept the agreement in the best interest of his clients. For us who knew the background of the matter, that vague objection, which was all that the attorney could put on record, spoke volumes. After accepting the Plea Agreement and before imposing sentence, the judge gave the defendants the right of allocution. Most of them chose not to say anything, but one who was the more articulate said humbly: “Your honor, you know that we are here because of the need of our families. I beg that you find it in your heart to send us home before too long, because we have a responsibility to our children, to give them an education, clothing, shelter, and food.” The good judge explained that unfortunately he was not free to depart from the sentence provided for by their Plea Agreement. Technically, what he meant was that this was a binding 11(C)(1)(c) Plea Agreement: he had to accept it or reject it as a whole. But if he rejected it, he would be exposing the defendants to a trial against their will. His hands were tied, but in closing he said onto them very deliberately: “I appreciate the fact that you are very hard working people, who have come here to do no harm. And I thank you for coming to this country to work hard. Unfortunately, you broke a law in the process, and now I have the obligation to give you this sentence. But I hope that the U.S. government has at least treated you kindly and with respect, and that this time goes by quickly for you, so that soon you may be reunited with your family and friends.” The defendants thanked him, and I saw their faces change from shame to admiration, their dignity restored. I think we were all vindicated at that moment.

Before the judge left that afternoon, I had occasion to talk to him and bring to his attention my concern over what I had learned in the jail interviews. At that point I realized how precious the interpreter’s impartiality truly is, and what a privileged perspective it affords. In our common law adversarial system, only the judge, the jury, and the interpreter are presumed impartial. But the judge is immersed in the framework of the legal system, whereas the interpreter is a layperson, an outsider, a true representative of the common citizen, much like “a jury of his peers.” Yet, contrary to the jury, who only knows the evidence on record and is generally unfamiliar with the workings of the law, the interpreter is an informed layperson. Moreover, the interpreter is the only one who gets to see both sides of the coin up close, precisely because he is the only participant who is not a decision maker, and is even precluded, by his oath of impartiality and neutrality, from ever influencing the decisions of others. That is why judges in particular appreciate the interpreter’s perspective as an impartial and informed layperson, for it provides a rare glimpse at how the innards of the legal system look from the outside. I was no longer sorry to have participated in my capacity as an interpreter. I realized that I had been privileged to bear witness to historic events from such a unique vantage point and that because of its uniqueness I now had a civic duty to make it known. Such is the spirit that inspired this essay.

That is also what prompted my brief conversation with the judge: “Your honor, I am concerned from my attorney-client interviews that many of these people are clearly not guilty, and yet they have no choice but to plead out.” He understood immediately and, not surprisingly, the seasoned U.S. District Court Judge spoke as someone who had already wrestled with all the angles. He said: “You know, I don’t agree with any of this or with the way it is being done. In fact, I ruled in a previous case that to charge somebody with identity theft, the person had to at least know of the real owner of the Social Security number. But I was reverted in another district and yet upheld in a third.” I understood that the issue was a matter of judicial contention. The charge of identity theft seemed from the beginning incongruous to me as an informed, impartial layperson, but now a U.S. District Court Judge agreed. As we bid each other farewell, I kept thinking of what he said. I soon realized that he had indeed hit the nail on the head; he had given me, as it were, the last piece of the puzzle.

It works like this. By handing down the inflated charge of “aggravated identity theft,” which carries a mandatory minimum sentence of 2 years in prison, the government forced the defendants into pleading guilty to the lesser charge and accepting 5 months in jail. Clearly, without the inflated charge, the government had no bargaining leverage, because the lesser charge by itself, using a false Social Security number, carries only a discretionary sentence of 0-6 months. The judges would be free to impose sentence within those guidelines, depending on the circumstances of each case and any prior record. Virtually all the defendants would have received only probation and been immediately deported. In fact, the government’s offer at the higher end of the guidelines (one month shy of the maximum sentence) was indeed no bargain. What is worse, the inflated charge, via the binding 11(C)(1)(c) Plea Agreement, reduced the judges to mere bureaucrats, pronouncing the same litany over and over for the record in order to legalize the proceedings, but having absolutely no discretion or decision-making power. As a citizen, I want our judges to administer justice, not a federal agency. When the executive branch forces the hand of the judiciary, the result is abuse of power and arbitrariness, unworthy of a democracy founded upon the constitutional principle of checks and balances.

To an impartial and informed layperson, the process resembled a lottery of justice: if the Social Security number belonged to someone else, you were charged with identity theft and went to jail; if by luck it was a vacant number, you would get only Social Security fraud and were released for deportation. In this manner, out of 297 who were charged on time, 270 went to jail. Bothered by the arbitrariness of that heavier charge, I went back to the ICE Search Warrant Application (pp. 35-36), and what I found was astonishing. On February 20, 2008, ICE agents received social security “no match” information for 737 employees, including 147 using numbers confirmed by the SSA as invalid (never issued to a person) and 590 using valid SSNs, “however the numbers did not match the name of the employee reported by Agriprocessors…” “This analysis would not account for the possibility that a person may have falsely used the identity of an actual person’s name and SSN.” “In my training and expertise, I know it is not uncommon for aliens to purchase identity documents which include SSNs that match the name assigned to the number.” Yet, ICE agents checked Accurint, the powerful identity database used by law enforcement, and found that 983 employees that year had non-matching SSNs. Then they conducted a search of the FTC Consumer Sentinel Network for reporting incidents of identity theft. “The search revealed that a person who was assigned one of the social security numbers used by an employee of Agriprocessors has reported his/her identity being stolen.” That is, out of 983 only 1 number (0.1%) happened to coincide by chance with a reported identity theft. The charge was clearly unfounded; and the raid, a fishing expedition. “On April 16, 2008, the US filed criminal complaints against 697 employees, charging them with unlawfully using SSNs in violation of Title 42 USC §408(a)(7)(B); aggravated identity theft in violation of 18 USC §1028A(a)(1); and/or possession or use of false identity documents for purposes of employment in violation of 18 USC §1546.”

Created by Congress in an Act of 1998, the new federal offense of identity theft, as described by the DOJ, bears no relation to the Postville cases. It specifically states: “knowingly uses a means of identification of another person with the intent to commit any unlawful activity or felony” [18 USC §1028(a)]. The offense clearly refers to harmful, felonious acts, such as obtaining credit under another person’s identity. Obtaining work, however, is not an “unlawful activity.” No way would a grand jury find probable cause of identity theft here. But with the promise of faster deportation, their ignorance of the legal system, and the limited opportunity to consult with counsel before arraignment, all the workers, without exception, were led to waive their 5th Amendment right to grand jury indictment on felony charges. Waiting for a grand jury meant months in jail on an immigration detainer, without the possibility of bail. So the attorneys could not recommend it as a defense strategy. Similarly, defendants have the right to a status hearing before a judge, to determine probable cause, within ten days of arraignment, but their Plea Agreement offer from the government was only good for . . . seven days. Passing it up meant risking 2 years in jail. As a result, the frivolous charge of identity theft was assured never to undergo the judicial test of probable cause. Not only were defendants and judges bound to accept the Plea Agreement, there was also absolutely no defense strategy available to counsel. Once the inflated charge was handed down, all the pieces fell into place like a row of dominoes. Even the court was banking on it when it agreed to participate, because if a good number of defendants asked for a grand jury or trial, the system would be overwhelmed. In short, “fast-tracking” had worked like a dream.

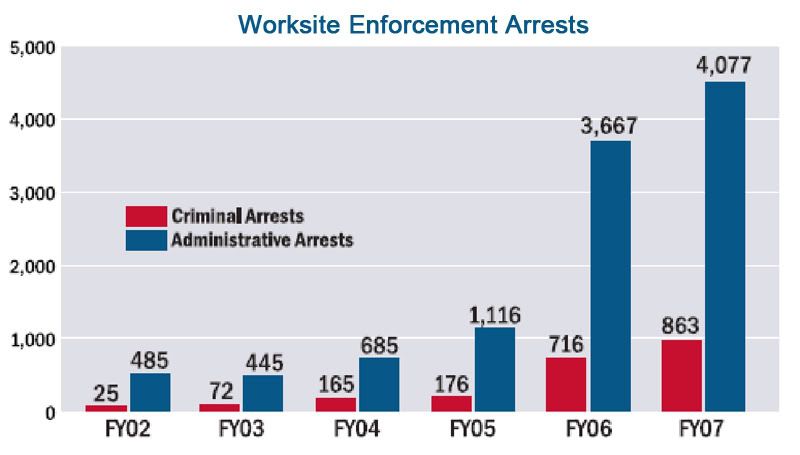

It is no secret that the Postville ICE raid was a pilot operation, to be replicated elsewhere, with kinks ironed out after lessons learned. Next time, “fast-tracking” will be even more relentless. Never before has illegal immigration been criminalized in this fashion. It is no longer enough to deport them: we first have to put them in chains. At first sight it may seem absurd to take productive workers and keep them in jail at taxpayers’ expense. But the economics and politics of the matter are quite different from such rational assumptions. A quick look at the ICE Fiscal Year 2007 Annual Report shows an agency that has grown to 16,500 employees and a $5 billion annual budget, since it was formed under Homeland Security in March 2003, “as a law enforcement agency for the post-9/11 era, to integrate enforcement authorities against criminal and terrorist activities, including the fights against human trafficking and smuggling, violent transnational gangs and sexual predators who prey on children” (17). No doubt, ICE fulfills an extremely important and noble duty. The question is why tarnish its stellar reputation by targeting harmless illegal workers. The answer is economics and politics. After 9/11 we had to create a massive force with readiness “to prevent, prepare for and respond to a wide range of catastrophic incidents, including terrorist attacks, natural disasters, pandemics and other such significant events that require large-scale government and law enforcement response” (23). The problem is that disasters, criminality, and terrorism do not provide enough daily business to maintain the readiness and muscle tone of this expensive force. For example, “In FY07, ICE human trafficking investigations resulted in 164 arrests and 91 convictions” (17). Terrorism related arrests were not any more substantial. The real numbers are in immigration: “In FY07, ICE removed 276,912 illegal aliens” (4). ICE is under enormous pressure to turn out statistical figures that might justify a fair utilization of its capabilities, resources, and ballooning budget. For example, the Report boasts 102,777 cases “eliminated” from the fugitive alien population in FY07, “quadrupling” the previous year’s number, only to admit a page later that 73,284 were “resolved” by simply “taking those cases off the books” after determining that they “no longer met the definition of an ICE fugitive” (4-5).

De facto, the rationale is: we have the excess capability; we are already paying for it; ergo, use it we must. And using it we are: since FY06 “ICE has introduced an aggressive and effective campaign to enforce immigration law within the nation’s interior, with a top-level focus on criminal aliens, fugitive aliens and those who pose a threat to the safety of the American public and the stability of American communities” (6). Yet, as of October 1, 2007, the “case backlog consisted of 594,756 ICE fugitive aliens” (5). So again, why focus on illegal workers who pose no threat? Elementary: they are easy pickings. True criminal and fugitive aliens have to be picked up one at a time, whereas raiding a slaughterhouse is like hitting a small jackpot: it beefs up the numbers. “In FY07, ICE enacted a multi-year strategy: . . . worksite enforcement initiatives that target employers who defy immigration law and the “jobs magnet” that draws illegal workers across the border” (iii). Yet, as the saying goes, corporations don’t go to jail. Very few individuals on the employer side have ever been prosecuted. In the case of Agriprocessors, the Search Warrant Application cites only vague allegations by alien informers against plant supervisors (middle and upper management are insulated). Moreover, these allegations pertain mostly to petty state crimes and labor infringements. Union and congressional leaders contend that the federal raid actually interfered with an ongoing state investigation of child labor and wage violations, designed to improve conditions. Meanwhile, the underlying charge of “knowingly possessing or using false employment documents with intent to deceive” places the blame on the workers and holds corporate individuals harmless. It is clear from the scope of the warrant that the thrust of the case against the employer is strictly monetary: to redress part of the cost of the multimillion dollar raid. This objective is fully in keeping with the target stated in the Annual Report: “In FY07, ICE dramatically increased penalties against employers whose hiring processes violated the law, securing fines and judgments of more than $30 million” (iv).

Much of the case against Agriprocessors, in the Search Warrant Application, is based upon “No-Match” letters sent by the Social Security Administration to the employer. In August 2007, DHS issued a Final Rule declaring “No-Match” letters sufficient notice of possible alien harboring. But current litigation (AFL-CIO v. Chertoff) secured a federal injunction against the Rule, arguing that such error-prone method would unduly hurt both legal workers and employers. As a result the “No-Match” letters may not be considered sufficient evidence of harboring. The lawsuit also charges that DHS overstepped its authority and assumed the role of Congress in an attempt to turn the SSA into an immigration law enforcement agency. Significantly, in referring to the Final Rule, the Annual Report states that ICE “enacted” a strategy to target employers (iii); thereby using a word (“enacted”) that implies lawmaking authority. The effort was part of ICE’s “Document and Benefit Fraud Task Forces,” an initiative targeting employees, not employers, and implying that illegal workers may use false SSNs to access benefits that belong to legal residents. This false contention serves to obscure an opposite and long-ignored statistics: the value of Social Security and Medicare contributions by illegal workers. People often wonder where those funds go, but have no idea how much they amount to. Well, they go into the SSA’s “Earnings Suspense File,” which tracks payroll tax deductions from payers with mismatched SSNs. By October 2006, the Earnings Suspense File had accumulated $586 billion, up from just $8 billion in 1991. The money itself, which currently surpasses $600 billion, is credited to, and comingled with, the general SSA Trust Fund. SSA actuaries now calculate that illegal workers are currently subsidizing the retirement of legal residents at a rate of $8.9 billion per year, for which the illegal (no-match) workers will never receive benefits.

Again, the big numbers are not on the employers’ side. The best way to stack the stats is to go after the high concentrations of illegal workers: food processing plants, factory sweatshops, construction sites, janitorial services — the easy pickings. September 1, 2006, ICE raid crippled a rural Georgia town: 120 arrested. Dec. 12, 2006, ICE agents executed warrants at Swift & Co. meat processing facilities in six states: 1,297 arrested, 274 “charged with identity theft and other crimes” (8). March 6, 2007 — The Boston Globe reports — 300 ICE agents raided a sweatshop in New Bedford: 361 mostly Guatemalan workers arrested, many flown to Texas for deportation, dozens of children stranded. As the Annual Report graph shows, worksite raids escalated after FY06, signaling the arrival of “a New Era in immigration enforcement” (1). Since 2002, administrative arrests increased tenfold, while criminal arrests skyrocketed thirty-fivefold, from 25 to 863. Still, in FY07, only 17% of detainees were criminally arrested, whereas in Postville it was 100% — a “success” made possible by “fast-tracking” — with felony charges rendering workers indistinguishable on paper from real “criminal aliens.” Simply put, the criminalization of illegal workers is just a cheap way of boosting ICE “criminal alien” arrest statistics. But after Postville, it is no longer a matter of clever paperwork and creative accounting: this time around 130 man-years of prison time were handed down pursuant to a bogus charge. The double whammy consists in beefing up an additional and meatier statistics showcased in the Report: “These incarcerated aliens have been involved in dangerous criminal activity such as murder, predatory sexual offenses, narcotics trafficking, alien smuggling and a host of other crimes” (6). Never mind the character assassination: next year when we read the FY08 report, we can all revel in the splendid job the agency is doing, keeping us safe, and blindly beef up its budget another billion. After all, they have already arrested 1,755 of these “criminals” in this May’s raids alone.

The agency is now poised to deliver on the New Era. In FY07, ICE grew by 10 percent, hiring 1,600 employees, including over 450 new deportation officers, 700 immigration enforcement agents, and 180 new attorneys. At least 85% of the new hires are directly allocated to immigration enforcement. “These additional personnel move ICE closer to target staffing levels”(35). Moreover, the agency is now diverting to this offensive resources earmarked for other purposes such as disaster relief. Wondering where the 23 trailers came from that were used in the Iowa “fast-tracking” operation? “In FY07, one of ICE’s key accomplishments was the Mobile Continuity of Operations Emergency Response Pilot Project, which entails the deployment of a fleet of trailers outfitted with emergency supplies, pre-positioned at ICE locations nationwide for ready deployment in the event of a nearby emergency situation” (23). Too late for New Orleans, but there was always Postville. . . . Hopefully the next time my fellow interpreters hear the buzzwords “Continuity of Operations” they will at least know what they are getting into.

This massive buildup for the New Era is the outward manifestation of an internal shift in the operational imperatives of the Long War, away from the “war on terror” (which has yielded lean statistics) and onto another front where we can claim success: the escalating undeclared war on illegal immigration. “Had this effort been in place prior to 9/11, all of the hijackers who failed to maintain status would have been investigated months before the attack” (9). According to its new paradigm, the agency fancies that it can conflate the diverse aspects of its operations and pretend that immigration enforcement is really part and parcel of the “war on terror.” This way, statistics in the former translate as evidence of success in the latter. Thus, the Postville charges — document fraud and identity theft — treat every illegal alien as a potential terrorist, and with the same rigor. At sentencing, as I interpreted, there was one condition of probation that was entirely new to me: “You shall not be in possession of an explosive artifact.” The Guatemalan peasants in shackles looked at each other, perplexed.

When the executive responded to post-9/11 criticism by integrating law enforcement operations and security intelligence, ICE was created as “the largest investigative arm of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)” with “broad law enforcement powers and authorities for enforcing more than 400 federal statutes” (1). A foreseeable effect of such broadness and integration was the concentration of authority in the executive branch, to the detriment of the constitutional separation of powers. Nowhere is this more evident than in Postville, where the expansive agency’s authority can be seen to impinge upon the judicial and legislative powers. “ICE’s team of attorneys constitutes the largest legal program in DHS, with more than 750 attorneys to support the ICE mission in the administrative and federal courts. ICE attorneys have also participated in temporary assignments to the Department of Justice as Special Assistant U.S. Attorneys spearheading criminal prosecutions of individuals. These assignments bring much needed support to taxed U.S. Attorneys’ offices”(33). English translation: under the guise of interagency cooperation, ICE prosecutors have infiltrated the judicial branch. Now we know who the architects were that spearheaded such a well crafted “fast-tracking” scheme, bogus charge and all, which had us all, down to the very judges, fall in line behind the shackled penguin march. Furthermore, by virtue of its magnitude and methods, ICE’s New War is unabashedly the aggressive deployment of its own brand of immigration reform, without congressional approval. “In FY07, as the debate over comprehensive immigration reform moved to the forefront of the national stage, ICE expanded upon the ongoing effort to re-invent immigration enforcement for the 21st century”(3). In recent years, DHS has repeatedly been accused of overstepping its authority. The reply is always the same: if we limit what DHS/ICE can do, we have to accept a greater risk of terrorism. Thus, by painting the war on immigration as inseparable from the war on terror, the same expediency would supposedly apply to both. Yet, only for ICE are these agendas codependent: the war on immigration depends politically on the war on terror, which, as we saw earlier, depends economically on the war on immigration. This type of no-exit circular thinking is commonly known as a “doctrine.” In this case, it is an undemocratic doctrine of expediency, at the core of a police agency, whose power hinges on its ability to capitalize on public fear. Opportunistically raised by DHS, the sad specter of 9/11 has come back to haunt illegal workers and their local communities across the USA.

A line was crossed at Postville. The day after in Des Moines, there was a citizens’ protest featured in the evening news. With quiet anguish, a mature all-American woman, a mother, said something striking, as only the plain truth can be. “This is not humane,” she said. “There has to be a better way.”

Erik Camayd-Freixas is Associate Professor of Spanish and Director of Translation and Interpretation Program, Florida International University.

|

| Print