Modern economic class struggle, the unremitting, sometimes hidden, sometimes open, fight between capitalists and workers that erupted in the 19th century and dominated the 20th, is taking on new forms and dimensions in the 21st century.

The stakes of this continuing conflict are higher than they have ever been. Every aspect of human life on earth is changing at an unprecedented rate, and three overriding trends that will affect the lives of everyone on the planet are now confirmed beyond any reasonable doubt.1 These three trends are:

- Increasing globalization

- Rising local, regional, and global inequality and growing absolute poverty — all factors that intensify political conflict

- Massive, irreversible, and, probably, catastrophic environmental damagecaused by unregulated economic activity

These three megatrends are interrelated — all of them are exacerbated by unrestrained free trade capitalism which relentlessly exploits resources and people for profit. The free trade policies adopted after World War II and reinforced in the 1980s have led to the present level of globalization that is stressing the resources and people of the world.

Globalization is the domination of the world economy by multinational corporations through the imposition of free trade policies and practices. Increasing globalization has been the prevailing form of capitalist expansion for the last 30 years and will intensify, along with the consequent rising inequality and environmental damage, as long as free trade policies continue unchecked.

Like all capitalist ventures, globalization has produced winners and losers. The winners have been few — the owners and agents of big capital — while small capitalists, labor, working-class communities, and the environment have clearly been the losers. The trends of rising local, regional, and global inequality and of growing absolute poverty that have produced political crises worldwide and massive and irreversible environmental damage so severe that it has triggered global climate change are direct consequences of these years of increasing globalization.

Confronting globalization and its negative consequences is the most crucial political challenge of the 21th century.

__________

What Is Globalization?

Capitalism’s insatiable need for new markets and the more thorough exploitation of existing ones in order to maximize profits is the driving force of globalization. For three decades, this imperative has been accommodated by bi-lateral and multi-lateral free trade agreements (FTAs) by which nations open their domestic markets (including labor markets) to each other. Under free trade covenants, countless local and national industries have been supplanted by mammoth multinational firms that utilize their inordinate economic power to promote policies that consolidate their dominant position.

Although globalization is often used as a buzzword, it has a very specific operational definition. Globalization refers to clearly identifiable networks of institutions and policies that facilitate the successful exploitation of communities and nations and their resources by multinational corporations. In order to successfully challenge globalization and dismantle the institutions and policies that have enabled it, a solid understanding of how globalization works is imperative. And although there are countless globalization schemes in operation around the world, the study of a single, representative case can reveal the basic mechanisms of globalization and suggest various strategies of resistance.

Toyota Motor Manufacturing, Texas (TMMTX) offers an excellent case study.

Why TMMTX?

TMMTX, a division of Toyota Engineering and Manufacturing, North America (TEMA), is a Texas-based subsidiary of the Toyota Motor Corporation of Japan (TMC). TMC, the seventh largest company in the world and the second largest manufacturer of automobiles, is set to surpass General Motors (GM) in 2008 and become number one in the auto industry. With over 50 manufacturing plants in 28 countries and profits in excess of $14.9 billion (¥1.7 trillion) reported for 2007, TMC is the world standard of globalization, and its policies and practices are imitated worldwide.

In addition, the fact that Toyota is presently operating 13 plants in North America, including TMC’s largest overseas operation, Toyota Motor Manufacturing, Kentucky (TMMK), belies the widely held misconception that globalization is something that is happening primarily in the developing countries of the global South and the Far East. Toyota operations in North America contribute directly to the forces of change that are racking the auto industry and undermining autoworkers and their communities across the continent.

TMMTX is a state-of-the-art auto manufacturing facility which began operations in 2006 to produce 200,000 full-size Tundra pick-up trucks per year. The $1.2 billion plant which employs over 2,000 workers sits on 2,600 acres of former ranch land just south of San Antonio, Texas. Situated in the developing I-35 NAFTA corridor 150 miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border and connected to the proposed I-69 NAFTA corridor to the east via I-10, the site is strategically located for globalized production and distribution to the world’s biggest auto market.

TMMTX is an excellent representative case — focusing the study of globalization on this one division of TEMA allows a concrete examination of how globalization works and its impact on local workers, their community, and the environment. The TMMTX study is important because it illustrates how the domination of capital over labor in the auto industry has been achieved through the active collaboration of the state. The TMMTX case study also debunks the myth that globalized manufacturing has triumphed because it is a superior mode of production.

The geographical location of TMMTX deserves particular attention.

The Southern Globalized Auto Plant Corridor

TMMTX is of special interest because of its location in the center of the southern globalized auto plant corridor that extends from Mexico City to Atlanta, Georgia (another Toyota plant is scheduled to open in the southern corridor at Blue Springs, Mississippi in 2010 and the company is presently searching for a site for a second manufacturing plant in Mexico).

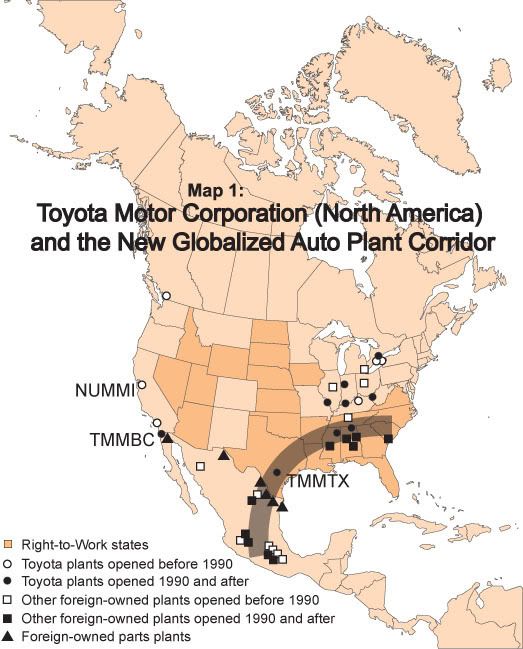

As illustrated in map 1, all except one of TMC’s plants in North America that have been opened since 1990 have been built in the southern globalized auto plant corridor. Any study of globalization in North America that fails to account for the development of this new manufacturing corridor is incomplete and inadequate for the task of confronting the issue. In addition to TMC, Honda, Nissan, Mercedes, BMW, and Hyundai/Kia have all opened manufacturing plants in the U.S. sector of this corridor since 1990, while Volkswagen, Nissan, and the Big Three U.S. automakers have all established or expanded production facilities in the Mexican sector. There are also over 50 automobile parts manufacturing plants in the corridor, mostly clustered along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Additionally, although Toyota Motor Manufacturing de Baja California (TMMBC) that opened in 2004 in Tijuana, Mexico is on the far side of the continent, it is an integral part of the same southern globalization trend.

The choice of a site in south Texas for the Tundra manufacturing facility in the southern auto production corridor illustrates a fundamental trend of globalization — the worldwide migration to the south in pursuit of cheap labor. Before closing the Texas deal, Toyota had considered alternative sites in Alabama, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Mississippi. A glance back at map 1 indicates what these states have in common — they are all anti-labor, Right-to-Work states, where wages and benefits for workers are well below those paid in the American Midwest and Canada and corporate taxes and regulations are minimal.

Though cheap labor is a primary criterion of offshoring and relocation, a close examination of the specifics of the deal that brought Toyota to Texas reveals that successful globalization schemes are not possible without the active collaboration of government at all levels, including massive transfer payments of public funds to multinational corporations.

Closing the Texas Deal

The TMC announcement in 2002 that the company was seeking a site for a major manufacturing plant in the southern auto plant corridor set off a round of competition in the region that Texas ultimately won. The initial incentive package offered to Toyota by city, county, and state governments surpassed $227 million.2

The Texas deal included the following:

- The City of San Antonio paid for the purchase and preparation of the 2,600 acre TMMTX site; waived the fees for the extension of water, sewer, electricity, and natural gas services to the plant; and agreed to sell electricity to the corporation for one-third of the price paid by residential customers. The city also agreed to establish a 3-mile buffer zone around the plant and “to exercise its best efforts” to annex the zone in order to protect the interests of TMMTX. The municipality also contributed several million dollars to construct a training center for TMMTX workers.

- The Southwest School District granted TMMTX a $45 million school tax abatement.

- Bexar County granted TMMTX a renewable, 10-year tax abatement worth $22 million and approved similar tax abatements to 15 TMMTX suppliers that totaled an additional $6.5 million.

- The state of Texas provided tens of millions of dollars of funding for road and rail infrastructure development to serve the plant, and millions of dollars to TMC and Alamo Community College to train workers for TMMTX.

- The Federal Government provided grants to the City of San Antonio, Alamo Community College, Bexar County, and the state of Texas to train TMMTX workers and provide transportation to and from work for them.

Table 1 summarizes the details of the incentives and abatements given to TMMTX that were publically acknowledged.

| Table 1: Incentives and Subsidies to TMMTX (Modified: March 22,2008) |

||||

| Date | Agency | Action | Costs | Final Payers |

| Feb. 2003 | Texas Transportation Commission | Initial grant to Bexar County to upgrade roads serving the TMMTX site | $17.6M | TX taxpayers |

| Apr. 2003 | TX Department of Economic Development, Smart Jobs Fund | Grant to Bexar County Rural Rail Transportation District to construct a second rail line to serve TMMTX | $15M | TX taxpayers |

| May 2003 | Incentive package for TMMTX (Project Starbright) agreement ratified. It included: | |||

| City of San Antonio | City incentive package to TMMTX (Includes $16.9 M to purchase 2,600 acre site, Toyota to contribute $2M. City to pay up to $10M site preparation, $3M for training center) |

$37 M | City taxpayers | |

| City of San Antonio | Fee waivers and extension of water and sewer services to TMMTX | $13M | City taxpayers, utility customers | |

| CPS Energy (City Public Service) | Fee waivers and extension of natural gas and electric service to TMMTX site. Toyota to pay 2.4 cents per kilowatt hour for electricity compared to 7.2 cents charged to residential customers | $1OM + un- determined amount from discount rate | Utility customers | |

| Bexar County | 10-year county tax abatement | $22M | County residents | |

| Southwest School District (SWISD) | School tax abatement. TMMTX agrees to pay up to $34M to offset losses from abatement | $45M | Public school students and employees | |

| Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) |

State funding for highway and road expansion projects | $26M | TX taxpayers | |

| Oct. 2003 | TxDOT | Development of Texas Highway 130 to avoid I-35 gridlock between San Antonio and Austin as inducement to TMMTX. First toll section of the I-35 NAFTA corridor. | Un- determined portion of $1.5B | TX taxpayers through bonds, road users through tolls |

| Dec. 2003 | US Department of Commerce. Economic Development Administration |

Grant to Bexar County and San Antonio to fund infrastructure improvements for TMMTX | $3M | US taxpayers |

| Feb. 2004 | Texas Workforce Commission, Skills Development Fund | Grant to TMC and Alamo Community College District (ACCD) to train workers for TMMTX | $2.15M | TX taxpayers |

| Feb. 2005 | Alamo WorkSource (Funded by state Skills Development Fund and US Department of Labor through Workforce Development Act) | Training Fund to reimburse TMMTX for training new workers. Renewable in 2008 if Toyota expands the plant. | $27.25M | TX and US taxpayers |

| Feb. 2005 | US Department of Commerce, Economic Development Administration | Grant to Palo Alto Community College (ACCD) to train TMMTX workers | $1.5M | US Taxpayers |

| June 2005 | Bexar County | 10-year county tax abatements granted to 15 TMMTX suppliers | $6.5M | County residents |

| Sept. 2005 | Project Quest Inc (non-profit) | Seeks funding to train TMMTX workers | Un- determined portion of $5M (2005) $7M (2006) |

Local taxpayers, foundations, and businesses |

| Oct. 2005 | US Department of Labor, Community-Based Jobs Training Initiative | Grant to ACCD to train TMMTX employees | $1.3M | US taxpayers |

| July 2006 | TxDOT | Grant to Alamo WorkSource to provide public transportation from economically distressed areas of San Antonio to TMMTX | $200,000 | TX taxpayers |

| Total of publically acknowledged incentives and subsidies to TMMTX through 2007. This total was compiled from reports published in the San Antonio Business Journal and the San Antonio Express-News. | $227.5M | |||

The total immediate cost of this single globalization deal to taxpayers is difficult to calculate because of hidden subsidies, but TMC public records offer a credible estimate. In 2006, the Toyota website reported a company investment of $780.2 million in the TMMTX plant which was valued at $1.23 billion on their books — this corporate disclosure indicates that public funds and assets transferred to TMC account for close to 40 percent of the total capital investment in the Texas auto plant!

Since the tax abatements are ongoing and renewable, the ultimate long range cost of the TMMTX deal to the community is inestimable.

Officials of the state of Texas justify the giveaway of public monies to corporations by citing the number of new jobs and general economic stimulus created by the businesses that receive the funds (www.governor.state.tx.us). However, to understand the overall impact of globalization projects like TMMTX it is necessary to examine the assembly plant as a link in an international production chain and assess the wider impact of the chain on working people, their communities, and the global environment.

TMMTX Operations: A Link in a Global Production Chain

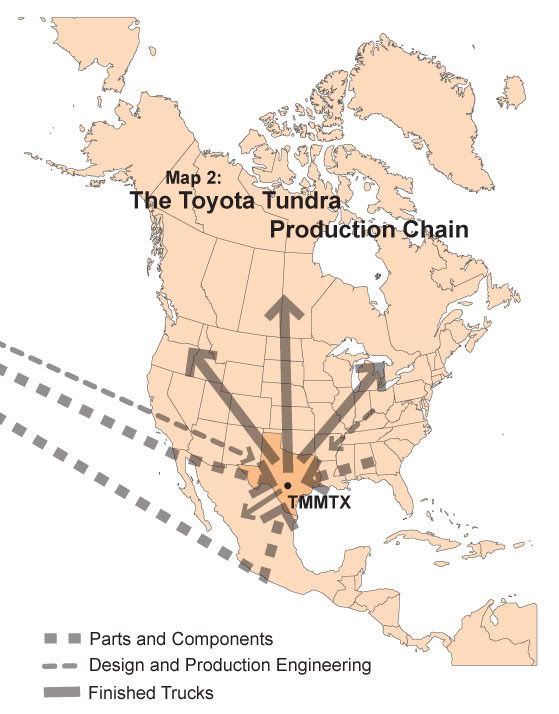

The TMMTX assembly plant is the focal point of a complex production chain that extends thousands of miles and has links to mines and manufacturing plants in the Far East, Mexico, and the southern U.S. It also has technological links to locations in Japan and the U.S. Midwest to access product engineering, production control, etc. The assembly plant is also the hub of an extensive transcontinental and export transportation network.

The strategic geographic location of TMMTX provides the company direct access to the low-cost south Texas labor market for assembly workers while insuring just-in-time delivery of cut-rate parts manufactured in the Far East and Mexico and subassemblies from other southern U.S. plants and providing convenient access to the U.S. auto market.

The production end of the chain concretely illustrates the driving force of globalization — to maximize profits by lowering labor costs. The relative cost of labor is the primary determinant in the location of every link in the chain. As many manufacturing operations as possible are completed in offshore labor markets, while the final assembly of the vehicles is conducted using some of the cheapest labor available in the U.S. Furthermore, the extensive use of automation technology in the TMMTX plant keeps the use of local labor to a minimum.

Promoters of globalization tout the Tundra production chain as a paradigm of efficiency and a compelling argument for this latest manifestation of mega-capitalism. However, the efficiency of global manufacturing, like any other capitalist enterprise, is measured by a single criterion — the revenue it produces for stockholders. Any analysis which takes the overall impact of globalization into account leads to a far different conclusion.

The impact of globalization on the corporation itself is a good starting point for such an investigation.

Impact I: The Corporation

TMC advertises its production operations as the most efficient in the auto industry and describes its system as “lean manufacturing.” Lean manufacturing is defined as “the production of the maximum number of sellable products or services at the lowest operational cost.” The system stresses teamwork, flexibility, and constant evaluation in order to maximize “throughput,” the rate at which the system generates revenue through sales. According to the corporation, the success of Toyota, including TMMTX, is the direct result of lean manufacturing.

The case study of TMMTX exposes the myth of lean manufacturing. Looking beyond the corporate rhetoric at the actual establishment and operation of TMMTX indicates that the extensive exploitation of cheap labor, both on- and offshore, and the substantial reduction of operational costs through state and local subsidies and tax abatements boost company revenues far more than the manufacturing practices in the plant, no matter how efficient they actually might be.

There is no doubt that globalization has benefited TMC at TMMTX and its other subsidiaries — the corporation reported profits of more than $15 billion worldwide in 2007 and anticipates continuing growth and increasing profits. The phenomenal “throughput” and profits of Toyota, however, must be measured against the impact of globalization on working people, their communities, and the environment.

Impact II: Labor

The success of globalization has clearly been at the expense of working people in North America and around the world. The imperative of globalization to exploit cheap labor markets has created conditions that are undermining labor on two distinct levels: first, by creating competition for work between the workers of different regional labor markets; and second, by stratifying workers within regional labor markets.

The case study of TMMTX demonstrates the partition of labor on both levels.

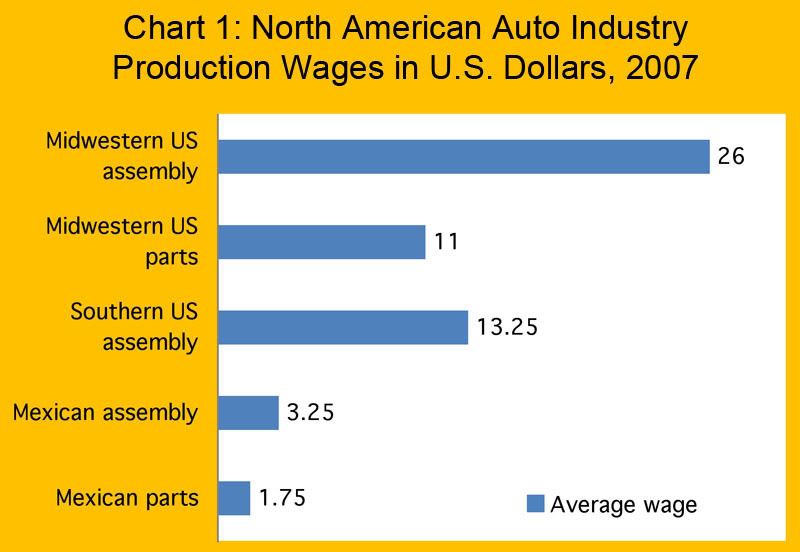

Chart 1 reports auto industry production wages in the United States and Mexico and depicts the globalized context in which TMMTX operates.

The regional disparity of wages depicted in chart 1 is stark. Midwestern U.S. assembly workers currently receive the top wages in the industry at an average of $26/hour. The sliding globalized pay scale is step — the average pay of southern U.S. assembly workers is $13.25/hour, slightly over half (51 percent) of the wages of workers in the Midwest. Mexican auto assemblers are at the bottom of the tiered labor market, making an average of $3.25/hour, a paltry 13 percent of the wages of their counterparts in the Midwest and less than 25 percent of assembly wages in the southern U.S.

Chart 1 also shows that the average wages of parts workers is about one half that of assembly workers in both countries. Mexican parts workers, making an average $1.75/hour, receive the lowest wages in the globalized North American industry, a mere 16 percent of the wages of parts workers in the Midwest ($11/hour).

The absence of a category for southern U.S. parts manufacturing in chart 1 is accounted for by the fact that southern U.S. plants, including TMMTX, rely primarily on Mexican factories for the bulk of their parts (see map 1). The proximity of this source of cheap auto parts is, in fact, a chief consideration in the location of new assembly plants.

Chart 1 documents the primary drive behind the globalization of the North American auto industry and its southward migration — the relentless pursuit of cheap wages.

Relocation of manufacturing plants (and threats of relocation), the backbone of capital’s strategy against labor in North America for the last 60 years, has now been fully realized through various globalization schemes and agreements like the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) which offers multinational corporations virtually unrestricted access to national and regional labor markets.

While pitting the workers of different regions against each other has been a boon to automakers, overall it has been an unmitigated disaster for labor. The impact of the globalization of the North American auto industry on labor in the Midwest has been devastating and includes the following consequences:

- The decimation of the United Auto Workers (UAW), formerly one on the strongest unions in North America.

- Declining auto industry employment in the Midwestand Canada.

- Continuing reduction of wages, benefits, and working conditions in the Midwest under the threat of further offshoring.

- Deteriorating economic welfare and security for all workers in the Midwest.

Though the impact of globalization on the traditional manufacturing regions is well documented (see “Globalization Now: The North American Auto Industry Goes South” at https://mronline.org/2007/10/16/globalization-now-the-north-american-auto-industry-goes-south/), successful confrontation with the system also requires recognition of the divisive impact of globalization within regional labor markets.

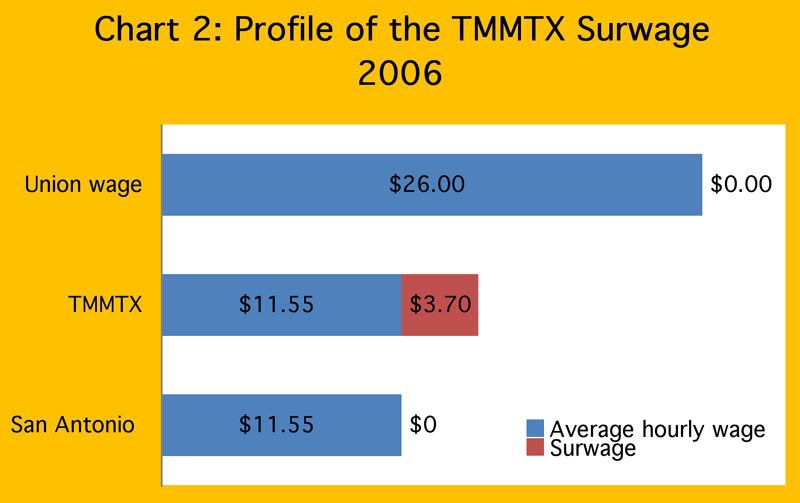

On the regional level, multinational corporations maintain control of labor markets primarily through the payment of carefully calculated surwages (wages significantly higher than average local wages but well below wages established by collective bargaining) that allow companies to manage regional wage rates and subvert attempts to unionize individual plants and entire regions.

Again, the case study of TMMTX supplies a concrete example of how this aspect of globalization works.

Chart 2 illustrates the TMMTX surwage in 2006.

Chart 2 compares the surwage paid by TMMTX to both the union assembly wage (for comparison) and the prevailing manufacturing wage paid in the San Antonio metropolitan area. In 2006, the starting hourly wage of a TMMTX assembly line worker was $15.25/hour, a full 25 percent greater than the average local manufacturing wage ($11.55/hour). These regional wage levels produced annual incomes of $31,720 versus $24,024/year.

The effects of the surwages on living standards in depressed labor markets are dramatic. The fact that the poverty threshold for a family of four in the U.S. was $20,614 in 2006 puts the San Antonio wage profile in chart 2 into perspective. $7,700/year at the bottom end of the income scale is very significant. With the additional earnings, a working family could afford better food and healthcare. It can also make the difference between living in a house versus an apartment, or of driving a decent car instead of a junker.

The divisive psychological effects of surwages on workers in the same plant or community are also significant. Employees receiving surwages know that that they are in a privileged position and are put on the defensive, while those who work for less are resentful. The partition of the working community through the strategy of paying surwages is very effective — union organizing appears as an unjustifiable risk for one side and seems futile for the other. The abject failure of union initiatives at TMMTX (as well as other plants in the southern auto plant corridor on both sides of the border) testifies to the efficacy of the surwage strategy.

The surwage strategy has been so successful for Toyota that it is now an essential element of corporate policy. In a five-year planning document that was leaked to the public in early 2007, the president of TEMA reiterated the company’s surwage policy and emphasized its importance for the future profitability and growth of Toyota in North America.

Two major aspects of the impact of globalization on labor, both concretely illustrated by the TMMTX case study, can be summarized at this point:

- The relentless pursuit of cheap labor, which has produced mass economic displacement and devastation for working people and their communities, is the driving force behind globalization (illustrated in chart 1). This trend (documented in map 1) clearly could not have been initiated and cannot be sustained without the collaboration of the state (shown in table 1).

- Multinational corporations maintain control of wages in regional labor markets through the payment of surwages that subvert unionization and help maintain low regional labor costs (profiled in chart 2). This control of regional wages, also aided and abetted by the state through anti-labor legislation, etc., is a key factor in the survival and expansion of globalization.

Beyond the direct effects on workers highlighted above are the broader impacts of globalization on host communities. Again, TMMTX provides clear examples.

Impact III: The Community

The economic impact of TMMTX on the community of south San Antonio parallels the impact on labor — while select individuals and groups clearly benefit from the presence of the plant in the area, the community at large is losing. The impact on the community is most clearly seen in the area of public education.

The loss of local community educational funds is a direct consequence of the tax abatements and diversion of public funds that were included in the incentive package granted to Toyota in 2003 (see table 1). Even before the TMMTX plant went online, the influx of new employees and their families into the community imposed increased demands on the local school district. A financial crisis emerged less than a year after the opening of the plant.

In 2007, the Southwest Independent School District (SWISD) which depends on local taxes for most of its operating funds challenged the $700 million dollar tax valuation on the $1.2 billion Toyota plant claiming a significant loss of revenue. On the same day that SWISD filed their challenge with the Bexar County Appraisal District (BAD) Toyota lawyers appeared before the BAD panel and also challenged the $700 million valuation, arguing that it should be lowered (to $300 million according to reports in the San Antonio Express-News).

The matter was settled when Toyota threatened to take BAD to court. The settlement testifies to the power of multinational corporations to influence local governments: BAD reduced the valuation of the TMMTX plant $73 million to $627 million. About the same time the state of Texas granted Toyota still another tax break for installing pollution control equipment that reduced the valuation by another $52 million to $575 million.

Because of the revaluation and tax abatements included in the original incentive package, SWISD received only $2.86 million in school taxes from Toyota for 2007. That figure will be reduced by over two-thirds in 2008 and subsequent years because the 2007 tax bill included a one-time $2 million payment that was part of the original tax agreement.

In the long run, the children and families of the SWISD will receive little, if any, social benefit from TMMTX being located in their community. The tax abatements granted to TMMTX and the company’s refusal to do its share to support local education stands in stark contrast to the millions of dollars of public funds that the corporation received from all levels of government to train TMMTX workers before the plant opened (see table 1).

The presence of TMMTX in south San Antonio has had similar impact on the entire spectrum of the social infrastructure of the community from healthcare to housing. However, a comprehensive accounting of community impact is beyond the scope of this study.

An overview of the environmental impact of the Toyota Tundra production chain rounds out the picture of the overall consequences of globalization.

Impact IV: The Environment

The case study of TMMTX also illustrates how globalization contributes significantly to mounting environmental damage. While TMMTX has been recognized (and further subsidized) by the state of Texas for being an environmentally responsible manufacturing plant, map 2 reveals that most of the Tundra production chain operates beyond the jurisdiction of any effective environmental protection agency, and, on the global level, Toyota worldwide operations contribute significantly to two environmentally ruinous trends.

First, globalization allows the externalization of industrial pollution by locating dirty manufacturing processes in countries with no environmental restrictions or lax enforcement of existing laws. Thus, while the Toyota assembly plant qualifies for tax breaks from the state of Texas for the installation of the latest pollution control equipment, it is utilizing parts and materials produced offshore under unregulated conditions. Auto batteries manufactured in Mexico and steel products mined and fabricated in the Far East are but two examples.

The second trend of environmental damage exacerbated by globalization is shipping industry pollution, a largely hidden but burgeoning source of dangerous atmospheric contamination. The tonnage of cargo transported by water has tripled since 1970, and, presently, ships carry more than 90 percent of the world’s commodities. According to the International Council on Clean Transportation, ships release more sulfur dioxide, a sooty pollutant associated with acid rain, into the air than all of the world’s cars, trucks, and busses combined, and the American Chemical Society estimates that air pollution from the shipping industry is causing 60,000 cardiopulmonary and lung-cancer deaths annually. The EPA predicts that, at the current rate of growth of the shipping industry, oceangoing ships will generate 53 percent of the particulates, 46 percent of the nitrous oxides, and more that 94 percent of the sulfur oxides emitted by all forms of transportation in the U.S. by 2030.

It is manifestly obvious that TMC’s extensive international production chains (and all global production chains) add to the expanding shipping industry pollution that is contributing to global environmental damage and climate change.

__________

Globalization: The Nexus of the Megatrends

The case study of TMMTX presents detailed concrete examples of how globalization schemes work and highlights the connections between the three megatrends of the modern world: ever expanding global production chains compound the ongoing catastrophic damage to the global environment and contribute to regional and global inequality, conditions that inevitably intensify both domestic and international political conflict.

The case study of TMMTX also exposes the essential political nature of the problem of globalization. Examining the establishment and operation of TMMTX shows that globalization is not a product of mystical “free market” forces but the end result of active collaboration between multinational corporations and the state.

The political implications of the study of globalization are clear — globalization will have to be confronted and dismantled the same way that it was enabled — through organized and relentless ideological and political action at all levels of government from the local to the international.

Confronting globalization is a daunting task but cannot be avoided. This challenge, the primary political contest of the 21th century, can only be initiated by working people who understand the implications of the global megatrends, but it will not be successful without the support of a broad-based coalition of committed people.

If we fail to act the whole world faces a precarious future.

1 Definitive and credible analysis of future trends can be found in The DCDC Global Strategic Trends Programme, 2007-2036 produced by the Development, Concepts and Doctrine Center (DCDC), a Directorate General within the UK’s Ministry of Defense (www.dcdc-strategictrends.org.uk/). The report is identified as “a source document of UK Defense Policy.” It is important to keep in mind that the primary objective of current UK Defense Policy is the same as that of the U.S. — the military defense of globalization.

2 State officials publically acknowledge only $133 million. The total of $227.5 million was derived from reports of incentives and subsidies published in local newspapers and business journals. The TMMTX deal was just the beginning of massive transfer payments to corporations. The Office of the Governor reports that since the Toyota deal was closed over $359 million of public funds has been granted to corporations through the Texas Enterprise Fund alone (2004-2007).

Richard D. Vogel is a political reporter who monitors the effects of globalization on working people and their communities. Other works include: “Stolen Birthright: The U.S. Conquest and Exploitation of The Mexican People “; “The NAFTA Corridors: Offshoring U.S. Transportation Jobs to Mexico”; “Transient Servitude: The U.S. Guest Worker Program for Exploiting Mexican and Central American Workers”; and “The Fight of Our Lives: The War of Attrition against U.S. Labor.” Contact: <[email protected]>.

|

| Print