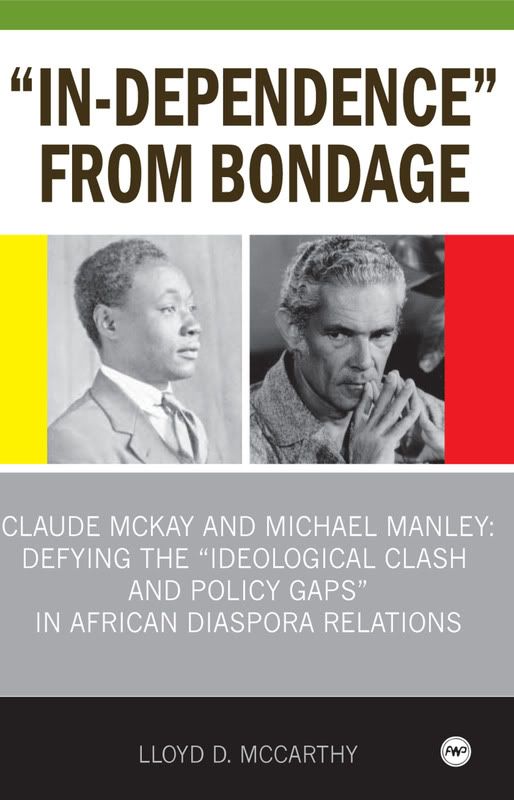

Lloyd D. McCarthy, “In-Dependence” from Bondage: Claude McKay and Michael Manley Defying the Ideological Clash and Policy Gaps in African Diaspora Relations (Africa World Press, 2007).

Claude McKay and Michael Manley may seem like strange bedfellows for a study in 20th-century politics. Though both born in Jamaica, a generation apart, they could hardly have pursued more divergent paths. McKay was a queer, Black communist poet who helped spark the Harlem Renaissance. Manley, of mixed African and European ancestry, was born into a politically aristocratic family and would eventually serve multiple terms as Prime Minister of Jamaica. Manley (1924-1997) was born on the inside track to politics and power, McKay (1889-1948) was the ultimate outsider for all of his days. Yet, in often contrasting ways, they both tried to articulate a politics that speaks for the poor and working-class people of the African Diaspora, in the Caribbean and beyond.

Lloyd D. McCarthy’s choice of characters for this analytic dual biography/regional history is ultimately rewarding. McCarthy draws attention to the logical connection between growing up on a colonized, hyper-exploited island and Manley and McKay’s eventual embracing of egalitarian, passionately anti-racist politics. McCarthy makes the case that Manley and McKay represent two archetypal political poles of 20th-century Caribbean radicalism. The two would scarcely have agreed on the question of reform or revolution — but McCarthy weaves his narrative in such a way as to make them brothers.

Lloyd D. McCarthy’s choice of characters for this analytic dual biography/regional history is ultimately rewarding. McCarthy draws attention to the logical connection between growing up on a colonized, hyper-exploited island and Manley and McKay’s eventual embracing of egalitarian, passionately anti-racist politics. McCarthy makes the case that Manley and McKay represent two archetypal political poles of 20th-century Caribbean radicalism. The two would scarcely have agreed on the question of reform or revolution — but McCarthy weaves his narrative in such a way as to make them brothers.

Manley and the Promise of Democratic Socialism

Born to a former Premiere of Jamaica and a well-known artist, Michael Manley was given a life of social and political connections across Jamaica. His debut in politics was as a fiery orator in the labor movement, stumping for the union associated with his father’s party. His charisma and famous name pushed him to the front of Jamaican populist politics, with a cult following amongst Jamaica’s working class. Elected in 1969 and riding a wave of popular mobilization, he sought to be the Prime Minister who stood for the poor, stood for Black people, and would speak out against imperialism. His record, ultimately, is mixed; he could take a righteous stand, but rarely followed through. His model of incremental, reformist socialism was no match for the IMF and the structural adjustments that further tore the economy apart.

Manley’s Democratic Socialist model aimed to “Jamaicanize” foreign businesses (state takeover of 51%), expand local capitalism, and nationalize some key institutions. The goal was to reallocate some economic power and provide basic relief to the poor, without scaring away foreign investors or domestic capital completely. Raised as a Fabian socialist, Manley attempted to rebuild Jamaica’s post-colonial economy along mixed public/private lines, not dissimilar to what other moderate Non-Aligned nations were experimenting with at the time. McCarthy overstates Manley’s commitment to socialist politics, claiming he had completely broken with his belief in the free market. The text suffers from a lack of thoroughgoing criticism of Manley’s time in office, choosing instead to highlight his rhetorical pronouncements and stated aims instead of holding them up to his actual record while in office. For all his indignation at the IMF’s role in global plunder, he was still willing to “structurally adjust” the Jamaican economy when they demanded it.

There is also no criticism of the extent to which Manley’s years in office were business as usual for Jamaican politics: cronyism, patronage, and street violence by rival party gangs. None of this changed under the rule of “socialist” Manley. As Arthur Lewin pointed out in Monthly Review in the aftermath of Manley’s (first) fall from power,1 the Manley administration focused the anger of the poor at the rival [conservative] Jamaica Labor Party, not actual economic elites. In short, Manley’s rule served to “mute class struggle,” containing the rebellious mood to the confines of mainstream, two-party politics. McCarthy credits Manley with inventing a non-revolutionary, “morally-based” Democratic Socialism perfectly suited for the Caribbean reality. McCarthy cites his early years as a Fabian socialist, his affinities with international anti-colonial struggles, and his resolute anti-racism as qualities that made his contribution to the Pan African Left so unique. In case you were wondering, the author worked high-level jobs in Manley’s cabinet.

There are also undeniably proud moments in Manley’s time in office. His commitment to the liberation struggles in Southern Africa was steadfast and extensive. He even floated the idea of Jamaica sending troops to fight in Southern Africa and applauded Cuba for doing just that. On the world’s stage, Manley was a loud and colorful voice against colonialism and white supremacy. Manley believed that the struggle against racism, especially in the Global South, was paramount to the struggle for human survival, even above the struggle between workers and capital. He was a product of an era of worldwide anti-imperialist struggle, and his political imagination was shaped by these movements. His commitment to smashing the legacy of racism played a role in domestic policy, too, with increased state commitments to fighting illiteracy and the gap in health care for Jamaica’s poor Black majority. His government was brought down by both US interference and its own contradictions, including his straddling both socialist-inspired and free-market approaches.

McKay’s Journey

Claude McKay’s grandparents were born into slavery, and McKay himself was brought up in a rural peasant environment. The language and oral history traditions of rural Jamaica would shape his poetry and prose for decades. It was in Jamaica that as a young man McKay, seeing plunder and racism everywhere, became curious about radical politics. After immigrating to Harlem, McKay found a growing Caribbean exile community, with quite a few radicals in its ranks. McKay met members of the IWW, the socialist/Black nationalist organization the African Blood Brotherhood, and all manner of agitators and leftist writers.

The year 1919 would change everything for Claude McKay, a year which also carries a morbid legacy for the radical labor movement and especially the Black community. It was the year of the Palmer Raids, when leftists and immigrants were targeted en mass for deportation. It was also know as the Red — with blood — Summer of 1919, when dozens of Black communities were faced with murderous pogroms and ruthless intimidation campaigns. Hundreds were killed in the violence, which also saw Black resistance to the onslaught. Claude McKay, an aspiring poet working as a waiter, grabbed a pen and wrote a poem at work, titled “If We Must Die.” The poem cried out in anguish at the slaughter being carried out against Black people and insisted that “if we must die” may it be on our feet, not on our knees. The poem was an incendiary call for vigorous self-defense. It struck a nerve with his co-workers and, via publications such as Max Eastman’s The Liberator, found resonance with Black people and their allies across the country. Despite his deepening connections with the Black Left, the labor movement, and radical literary circles, McKay prepared to migrate again, this time to London and eventually the Soviet Union.

In the young Soviet Union, it was reported, workers had overthrown bosses and racism was quickly vanishing. Transfixed with such a notion, McKay went to see for himself. As a relatively young, Black communist and intellectual, McKay was greeted warmly by members of the Communist movement across Russia. Indeed he got quite a grand tour of the young USSR: meetings with Leon Trotsky to discuss the National Question, time spent training with the Red Army, speaking engagements at all manner of political events, attending May Day demonstrations, and arguing on behalf of American Blacks at lecterns across the country. He was something of a socialist celebrity, reading his poems to cheering cadres and soldiers. But McKay’s wanderlust (and uneasiness with still persistent racism) pulled him away from the USSR, towards North Africa, and across Europe many times, all the while continuing his work as a poet and novelist.

When McKay returned to Harlem in the mid-1930s, fragments of the Caribbean exile Left had helped give rise to a formidable branch of the Communist Party. Let down by the continuation of bigotry under Soviet rule — particularly anti-Semitism — and the rising authoritarianism of the Stalin era, McKay became burned out on the official Communist movement. By the time the Communist Party had established itself in his old neighborhood, McKay looked at the party as cynically exploiting the political desires of Blacks.

McKay’s vision, as McCarthy spells out quite clearly through pieces of McKay’s prose, poetry, and political writing, was one of Black liberation and socialism. He believed that capitalism and imperialism had robed the Third World — and especially the African Diaspora — of its wealth and dignity. The reclamation of human rights can not come through reform of capitalism, but rather through the emergence of a socialist alternative. He was Afrocentric and a Pan Africanist long before the ascension of those outlooks and was an anti-imperialist a generation before those movements would shake the world.

Manley and McKay

Michael Manley, too, believed that capitalism and imperialism had robbed Black people and people of the Global South of their rights and resources. McKay was inspired by the formation of a world revolutionary movement, and Manley had his eye on international possibilities as well. Manley imagined a European Union-style trading block that would help primarily countries of the Global South. McKay believed that only revolutionary action could wrestle power away from the ruling class, while Manley insisted on an inside-the-system approach that sough a middle path between capital and labor. Both identified their Afro-Caribbean roots as being essential early building blocks towards their radical politics. McKay and Manley both saw themselves as voices for the masses of poor and working-class people of African ancestry across the globe, and both saw themselves as stemming the tide of generations of cultural genocide and extreme exploitation.

The many simpatico ways these men’s lives and ideas dovetail each others are looked at in great detail and indeed illuminated by Lloyd McCarthy. The unflattering ways they do not line up, however, are glanced past. McCarthy is unable to see the yawning gap between Manley’s socialist-sounding rhetoric and the zig-zag political realities of his administration. It is a bit simpler to analyze McKay’s politics, as he never wielded state power. His vivid mixture of Black Nationalism, anti-colonialism, and radical socialism found a burning expression on the page, but was never tested on the ground. Therefore it is McCarthy’s light, sympathetic treatment of Manley that is the most suspect.

McCarthy’s book is a joy to read, a rich look at the 20th-century Caribbean Left as represented by two of its most charismatic and brilliant thinkers, though the author, it would seem, is simply a little too close to Manley’s legacy to give it an objective appraisal.

1 “The Fall of Michael Manley: A Case Study of the Failure of Reform Socialism,” Monthly Review 33.9, February 1982: 49-60.

Brad Duncan lives in Detroit and writes for Against the Current, Australia’s Green Left Weekly, and Detroit’s Metro Times.

|

| Print