I wanted a roof for every family, bread for every mouth, education for every heart, light for every intellect. I am convinced that the human history has not yet begun — that we find ourselves in the last period of the prehistoric. I see with the eyes of my soul how the sky is diffused with rays of the new millennium. — Bartolomeo Vanzetti

Commemoration on the Streets of Boston

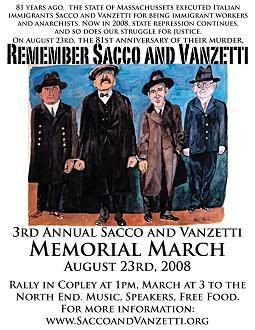

This past weekend marked 81 years since the execution of the two most famous class-war prisoners in our history, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, electrocuted in Massachusetts on 23 August 1927 on false murder charges, framed by the state for their anarchist convictions and activism. Since a proclamation by Gov. Michael Dukakis in 1977, the 23rd of August has been recognized as a kind of Sacco and Vanzetti Memorial Day in Massachusetts, the past three years revitalized with a march and rally organized by the Sacco and Vanzetti Commemoration Society in Boston, on whose Web site you can see a video of the 23 August 2008 march. There is a recent official proclamation by the Boston City Council supporting the SVCS and the August 23rd commemoration events.

This past weekend marked 81 years since the execution of the two most famous class-war prisoners in our history, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, electrocuted in Massachusetts on 23 August 1927 on false murder charges, framed by the state for their anarchist convictions and activism. Since a proclamation by Gov. Michael Dukakis in 1977, the 23rd of August has been recognized as a kind of Sacco and Vanzetti Memorial Day in Massachusetts, the past three years revitalized with a march and rally organized by the Sacco and Vanzetti Commemoration Society in Boston, on whose Web site you can see a video of the 23 August 2008 march. There is a recent official proclamation by the Boston City Council supporting the SVCS and the August 23rd commemoration events.

The Socialist Party Boston also participated together with the SVCS in this year’s rally across from the old North Church in Boston’s North End. It was endorsed by other groups, including the Boston May Day Coalition, calling for a halt to state repression against immigrant workers. You can hear participants from the march and speakers from the Boston Anti-Authoritarian Movement (BAAM) and other groups among those who addressed the rally, including local union organizers and Boston City Councilor Chuck Turner. They linked present anti-immigrant hysteria with the climate surrounding the Sacco and Vanzetti show trial and travesty of justice. In Massachusetts this past month, Operation Community Shield rounded up hundreds from the immigrant and refugees communities for detention and possible deportation.

State Repression Mounting

Raid in Jones County/MS

Less than 48 hours after the commemoration in Boston, on 25 August, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) conducted a raid at Howard Industries in Laurel, Mississippi that resulted in the arrest of nearly 600 immigrant workers. Among the many arrested were mothers, about 100 of whom were fitted with electronic monitoring bracelets and allowed to go home to their children. This is the largest single-workplace immigration raid in US history, a move harkening “back to Mississippi’s shameful past of Jim Crow segregation, police brutality and violence,” in Jones County, once truly notorious as a center for KKK activity. In Poplarville, a short drive south of Laurel, the KKK staged an anti-immigration rally last year. During the 2007 elections, the Klan held a rally of 500 people in front of the Lee County courthouse in Tupelo in northern Mississippi, carrying signs saying, “Stop the Latino Invasion.”

Running down the Walls!

Simultaneous with commemoration in Boston, a run/walk/bike was held in California in support of class-war and political prisoners and POWs in the U.S. prison system “in honor of former political prisoners Sacco and Vanzetti.” The call to participate in the event, issued by the Los Angeles Anarchist Black Cross Federation, notes that today’s PP/POWs in the US “have been unfairly incarcerated while fighting for social justice and self-determination. They are our generation’s Sacco and Vanzetti.”

Stop the Raids, Detentions, Deportations!

Important here is the link between remembering Sacco and Vanzetti and current state repression against immigrant workers and families, class-war and political prisoners, the broader question of the death penalty, and the demonizing of dissident views. Peter Miller’s Sacco and Vanzetti, reviewed in MRZine by Michael D. Yates in December 2006, is a powerful documentary available on DVD. Peter discusses it in an interview, emphasizing that the film is also about immigrants, justice, and ethnicity in America today.

Similarly, the SVCS stresses:

We invoke our local history not only to remember Sacco and Vanzetti, but also to demonstrate how little has changed in the 81 years following their execution. Nationalist fear-mongering and the repression of dissidents is as prevalent today as it was during the Red Scare in the early 20th century. The way in which immigrants workers are rounded up, detained, and deported today under the pretext of a War on Terror, a War on Drugs, or securing our borders is eerily similar to the Palmer Raids targeting immigrants in the 1920s.

Repression against the undocumented is reaching a new high water mark across the US.

International Workers’ Solidarity

Nicola labored in a shoe factory in Stoughton, Bartolomeo was a fish peddler on Suassos Lane, an alley in north Plymouth. Some 25,000 demonstrated in Boston on the eve of the execution, and hundreds of thousands more in the streets in a “Death Watch” across the US. Police clashed with some 50,000 gathered in New York’s Union Square. 600,000 had signed a petition for a new trial. In Colorado, half the state’s miners responded to an IWW call for a two-day protest strike on 21 August 1927 against the planned execution. This action led directly to the IWW-organized massive miners’ strike in Colorado from October 1927 to February 1928, with the Columbine mine massacre on 21 November.

The prisoners were burned in the electric chair in Boston’s Charleston Prison shortly after midnight on the 23rd of August. At the funeral, 100,000 workers marched, arm in arm, defying the police. In Paris, large angry crowds descended on the US Embassy. There were mass vigils and rallies from Casablanca to Caracas, Munich to Mexico City. Proletarian support in Argentina was especially strong, igniting a general strike in Buenos Aires and later attacks on US firms and banks, organized in part by the Italian anarchist Severino Di Giovanni. This was the largest worker-led transnational protest campaign in modern history.

The convicting judge Webster Thayer, in referring to Sacco in his jury instructions, said: “Although this man may not have committed the crime attributed to him, he is nonetheless culpable because he is the enemy of our existing institutions.” He boasted to associates about what he had done to “those anarchist bastards.” After Thayer’s home was bombed in 1932, he lived the last year of his life under 24/7 police guard at his club in Boston.

Sacco addressed Thayer after the death sentence on 9 April 1927:

I know the sentence will be between two classes, the oppressed class and the rich class, and there will be always collision between one and the other. We fraternize the people with the books, with the literature. You persecute the people, tyrannize them and kill them. We try the education of people always. You try to put a path between us and some other nationality that hates each other. That is why I am here today on this bench, for having been of the oppressed class. Well, you are the oppressor.

Italian Anarchist Solidarity

Workers’ protest against the execution was in evidence even in fascist Italy in the mid-1920s and the supposed support of dictator Mussolini for their release. Their remembrance is enshrined in Italian public memory as part of its heavy “American baggage.” Last year the memory of Nicola Ferdinando Sacco was specially commemorated in his birthplace Torremaggiore in Apulia in Italy’s southeastern ‘heel.’ This year, in Torremaggiore, the Federazione dei Comunisti Anarchici participated 22-23 August in a vigil organized by the Associazione Sacco & Vanzetti, in cooperation with Amnesty International, Nessuno Tocchi Caino, and the World Coalition Against The Death Penalty, expressing solidarity with Afghan journalist Sayed Perwiz Kambakhsh, sentenced at home to death for blasphemy. A highpoint of the event was the appearance of Maria Fernanda Sacco, granddaughter of Nicola. She is honorary president of the Associazione. Maria Fernanda presented her new book, I miei ricordi di una tragedia familiare (My memories of a family tragedy), published in mid-August.

The FdCA stresses that today in Italy, “episodes of racism and intolerance (including institutional racism and intolerance), the violation of the human rights of asylum-seekers and Roma, the violation of human rights in prisons and immigrant detention centres, the day work and untrammeled exploitation on farms, all testify to the importance even today of the fate of the two Italian anarchists murdered in America, of their cry for freedom, dignity and social justice.” This is especially true in the current anti-immigrant political climate across Italy and government crackdown on Roma migrants from the Balkans. The EU is especially concerned about the ‘socioeconomic inclusion’ of the Roma subaltern class into its structures of neoliberalism.

Through an Italian Lens

Guiliano Montaldo’s feature film Sacco e Vanzetti (1971) can now be viewed in full in the original Italian online. Its first scene reconstructing a brutal police raid on Italian immigrant workers in Boston, without dialogue, is riveting and true to history. This extraordinary film needs to be re-released with English subtitles and made available to a worldwide audience. Fabrizio Costa’s recent TV film Sacco e Vanzetti (2005) likewise needs to be released with English subtitles. It has been well received by some on the anarchist Italian Left as a ‘remake’ of Montaldo’s flick. A lesser-known documentary in English that deserves broad distribution, directed by Italian-born anarchist scholar and activist Pietro Ferrua, was telecast in 1988 on the History Channel, The True Story of Sacco and Vanzetti.

A Rich Cultural and Media Legacy

Political Ballad Online

Dave Rovics performs Woody Guthrie’s “Two Good Men” (its lyrics here). Guthrie was commissioned in 1945 by Moe Asch, radical Warsaw-born son of novelist Sholem Asch and later founder of Folkways Records, to write 12 ballads about Sacco and Vanzetti, recorded in 1946-47. Woody called the assignment “the most important dozen songs I’ve ever worked on,” but was not very pleased with what he produced. The recordings were finally released in 1964 on Folkways. One of the great songs is “Root Hog and Die.”

Joan Baez sings “Here’s to You” and the “Ballad of Sacco and Vanzetti” (first two parts, music by Ennio Morricone, from the 1971 Montaldo film, full lyrics online. If you know German, powerful is Franz-Josef Degenhardt‘s song about Sacco and Vanzetti — coupled with reference to Angela Davis, written in 1970 when Angela was behind bars.

Lyric Poetry

Many poems over the years, in many languages, are collected on the Web site of the Sacco and Vanzetti Commemoration Society, a representative sampling in English. Memorable is Wobbly troubadour Jim Seymour’s poem “Sacco and Vanzetti,” which looks at the virulent racism directed against “a couple o’ God damn dagoes!” (in J.L. Kornbluh, ed., Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology, 1988, p. 358).

Three Neglected Novels, Two Buried Teleplays, a Classic Silent Film

Howard Fast’s The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti (1953) is a documentary novel centering on the doomed men’s final hours. Its title echoes Ben Shahn’s 1932 painting, “The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti,” now in the Whitney Museum in NYC. In a moving interview in August 2002 nine months before his death, Fast spoke about the book and his concerns for American democracy.

Howard Fast’s The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti (1953) is a documentary novel centering on the doomed men’s final hours. Its title echoes Ben Shahn’s 1932 painting, “The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti,” now in the Whitney Museum in NYC. In a moving interview in August 2002 nine months before his death, Fast spoke about the book and his concerns for American democracy.

Upton Sinclair’s Boston (1928) is the major documentary novel by an American radical writer dealing centrally in detailed depth with Sacco and Vanzetti and their long ordeal. This compelling ‘faction’ (nearly 800 pp.) also sketches a portrait of the virulent climate of social and political bias that festered in Boston and across the U.S. in the mid-1920s. Howard Zinn knew the novel from his teens and wrote the introduction to its reissue by a small Boston publisher (Bentley) in 1978, stressing: “It is a history of the Sacco-Vanzetti case truer than the court transcript, more real than any non-fiction account, precisely because it goes beyond the immediate events of the case to bring the reader the historical furnace in which the case was forged [. . .] It puts the straight lines of neutral type in the law books under a microscope, where they show up as rows of trenches in the war of class against class” (The Zinn Reader: Writings on Disobedience and Democracy [1997], p. 474). Its German translation reached a print run in Malik Verlag of 75,000, and was widely read on the proletarian Left in the late Weimar years.

The heated discussion that rocked the media — mainstream, left and right — in December 2005 and into the spring of 2006 sparked by a newly surfaced letter written by Sinclair expressing doubts about the pair’s innocence is placed in proper perspective in a Zinn interview. The novel itself is still seldom cited and rarely read.

Forgotten is a novel by the proletarian writer Nathan Asch, older brother of Moe Asch, likewise born in Warsaw: Pay Day (1930). Set against the backdrop of the Sacco and Vanzetti execution, it centers on an average Manhattan office clerk, Jim Cowan, as he runs after a few hours of pleasure in New York the night of 22 August 1927, blowing a miserable week’s pay in a grim picture of urban white-collar working-class existence. Its translations into German (Der 22. August), Yiddish (Der tsveyuntsvantsikster Oygust), and Spanish (22 de agosto), the title foregrounding the execution, were much read in Weimar Germany, Poland, and Spain. In one episode, Jim hears a guy in the subway train talking about what happened in Boston that night:

Try to think of a way to reach them, these rulers of the country for whose benefit all this was arranged, as a warning, as a lesson. Somehow try to wake them up. Words mean nothing to them [. . .] The newspapers have been screaming headlines at them for months. They read them and look elsewhere. . . . Two men are hounded and framed into death. More headlines. Always the same. The sports page is more interesting, the comic page more amusing. [. . .] Find a way to wake them, to make them realize words. Try to talk to them, to make them understand. Do something.

The novel was reissued in 1990, but Nathan’s works remain little known, one of our most eclipsed major socialist fictionists.

Sidney Lumet’s controversial NBC teleplay The Sacco-Vanzetti Story (1960) is an incisive Emmy-nominated 2-part piece, by one of Hollywood’s greatest directors; it ought to be reissued on DVD. The BBC aired a teleplay The Good Shoe Maker and the Poor Fish Peddler (1965), directed by John Gorrie, that also needs to be made available. Shortly after the execution, Austrian-Hungarian film director Alfréd Deésy did a silent film, Sacco und Vanzetti, starring the later famed Austrian actor Louis V. Arco, copies of which probably still exist.

An Opera Finally Completed

Radical composer Marc Blitzstein was working on a three-act opera Sacco and Vanzetti (1959-1964), which Marc envisioned as his magnum opus, when he was attacked and murdered in Martinique in 1964. The opera was completed 37 years later by his associate, the composer Leonard Lehrman, and premiered in Connecticut in 2001:

A particularly telling passage in Act III shows the anti-immigrant prejudice, against which Blitzstein fought all his life, in a conversation among the panel appointed by Governor Fuller to advise him on whether or not to pardon Sacco and Vanzetti. Judge Robert Grant, whose luggage had been stolen on a trip to Italy, declares: “It is a well-known fact that all Italians lie and steal.” Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell, who tried to prevent Justice Brandeis from ascending to the Supreme Court, concurs: “Just like Jews.”

A Major Anarchist Play

The German-Jewish anarchist poet and activist Erich Mühsam, murdered by the Nazis in July 1934, wrote the classic drama on the ordeal of Sacco and Vanzetti, completed for the political theater of Erwin Piscator in Berlin on the first anniversary of their death, entitled Staatsräson. Ein Denkmal für Sacco und Vanzetti (Reasons of State. A Memorial to Sacco and Vanzetti). It covers the legal case from May 1920 until the execution, and remains a unique piece for the anarchist political theater in 15 scenes or Bilder. The play was issued in English translation by C.R. Edmonston on 23 August 2007, and is available at the SVCS website. The stage play deserves production in North America, and can be used for Readers Theater in the schools, even some street theater skits. Mühsam’s poetry, drama and theoretical work need to be far better known, such as his 1933 treatise Die Befreiung der Gesellschaft vom Staat (The Liberation of Society from the State), an anarchist classic as yet untranslated into English. There’s a Mühsam Society in his home town Lübeck.

In Scene 14 just before the electrocution, Nicola tells his wife Rosa to give this message to their14-year-old son Dante:

Above all, impress upon him that he must never be set on his own good fortune alone, but must stand by the weak and helpless and aid the persecuted. Only the poor are his true friends, only the comrades who are ready to fight and fall, like his father and Bartolomeo have fallen in the fight for the happiness and freedom of the proletariat. [. . .] Later, Dante will understand that this is a battle between rich and poor, between law and freedom. I tell him this from the house of death. May he help turn this house to rubble with the hammers of socialism and anarchy and bring it about that workshops of free labor and schools of truth for orphans and minors be erected where prisons and places of execution once stood.

The full German original is also online.

Lotta Continua

As Michael D. Yates wrote: “The horrible injustices done to Sacco and Vanzetti are being suffered by all too many people right now. [. . .] Sacco and Vanzetti make us proud to be human beings and prouder still to be radicals. They also force us to recommit ourselves to the struggle for human liberation.” Sergio Reyes of the Boston May Day Coalition, a Chilean immigrant and former political prisoner in Pinochet’s Chile, closed the SVCS rally in the North End on August 23, underscoring that those assembled were keeping the memory of Sacco and Vanzetti “alive on the streets of Boston, in practice, in deed, and we come right here to the heart of the Italian neighborhood to remember members of their community that were persecuted in the past, that were victimized, that were in the end murdered by the state [. . .] Compañeros, the people united will never be defeated!”

Bill Templer is a linguist based in Southeast Asia.

|

| Print