Deteriorating economic and social conditions in Mexico have generated mounting social problems. Private enterprises in Mexico and the government they control cannot manage, let alone solve them. Huge demonstrations are rocking the country with more to come. One chief cause of Mexico’s problems is the turmoil and decline in the US economy. Rising US unemployment lessens its appeal for poor Mexicans seeking to escape their country’s gross economic inequalities and lack of opportunity for a decent life. Cash that Mexican immigrants in the US send back to their families — “remittances” is its formal name — has stopped growing and begun a significant decline. What were major offsets to Mexico’s disastrous economic conditions — sending able-bodied workers out of the country and then siphoning part of their US earnings back into it — have changed into their opposites: threats to destabilize Mexican society.

For many years, the US official policy towards Mexico was based on choosing between Mexican economic and social instability and allowing Mexican immigration into the US. Republicans and Democrats alike consistently chose immigration. It solved the economic problems of a Mexican capitalism that was and remains extremely unjust in its distributions of wealth, income, and well-being and extremely inefficient in utilizing its labor force. First, migration to the US gave desperate Mexicans, and especially men, a way to escape that country’s failure to provide decent jobs or incomes to millions of its citizens. Mexico thus exported what might otherwise have become a politically dangerous mass critical of Mexican capitalism. Second, it generated those remittances back into Mexico that kept afloat an economy that would otherwise have provoked social unrest and revolutionary movements among those unable or unwilling to emigrate to the US. Both mass emigration and massive remittances kept the Mexican economic disaster from becoming an active social crisis on the US border.

Immigration likewise suited US businesses by providing millions of new workers (especially those immigrants fearful about their illegal status) willing to accept lower wages and benefits than were the US norm. All sorts of gains accrued to US employers of Mexican immigrants (in agriculture, construction, retail, and beyond). Vast profits were made by the US financial companies through whom Mexican immigrants sent their remittances home. A recent World Bank report found that banks and other agencies (such as Western Union) charged an average of 4 to 8 per cent of each remittance as payment for transferring the money from the US to Mexico (a trivial and nearly costless electronic transfer process). Such employers made sure that anti-Mexican immigrant policies were never effective.

There were the usual hyped public relations gestures by politicians pandering to US movements against Latino immigration. However, business interests, the immigrant communities themselves, and liberal groups prevailed against those movements. The inflow of Mexican immigrants and the outflow of remittances to Mexico were not stopped by political means. It has been US capitalism’s credit meltdown and its consequences that have changed the economic links between Mexico and the US.

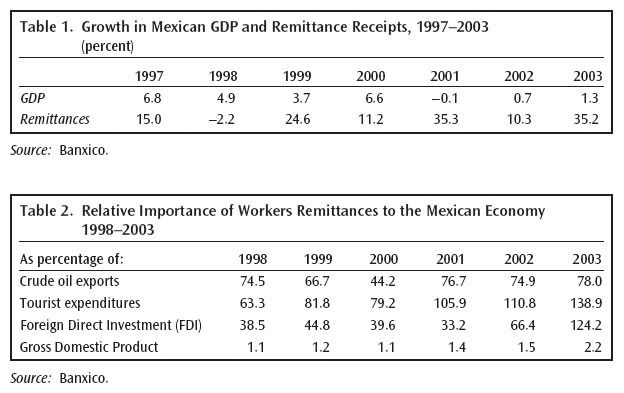

The dependence of Mexico’s extremely unequal capitalism on emigration and remittances is stark. In the most thorough study to date, the World Bank’s Raul Hernandez-Coss found that in 2003, remittances were a much larger inflow of money into Mexico than both total tourist expenditures inside Mexico and total foreign direct investment in Mexico.

SOURCE: Raúl Hernández-Coss, “The U.S.-Mexico Remittance Corridor: Lessons on Shifting from Informal to Formal Transfer Systems,” World Bank Working Paper No. 47, 2005, p.4

That has remained the case through 2007. Only oil and other exports brought in more money. And the prospects for Mexico’s future oil production are declining while those for many other Mexican exports are being dimmed by devastating competition from Chinese and other Asian exports.

SOURCE: “U.S. Slowdown Hits Mexico as Remittances Drop,” Wall Street Journal, 30 July 2008 |

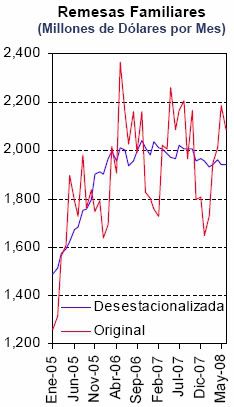

Remittances grew many times faster — peaking at $24 billion in 2006 — than gross domestic product in Mexico over the last decade, thus becoming an ever more important support for an otherwise increasingly dysfunctional economy. The consensus estimate of researchers is that 20 per cent of Mexican families — many among the nation’s poorest — now depend significantly on remittances for their basic incomes. Since many transfers are made through illegal and other channels not counted by the gatherers of statistics, it is certain that all official estimates are in fact underestimates of the actual remittance flows and their importance.

On July 30, 2008, the Mexican central bank reported a 3 per cent drop in remittances this year. As jobs shrink in the US economy — initially in the construction and housing industries and then spreading to the retail and other industries that employ many Mexican immigrants — immigration into the US is slowing and remittance flows to Mexico will shrink further. Either alone is a threat to Mexico; both together may explode its economy and society.

Already the signs of explosion are proliferating. Drug traffic and the vast network of employment opportunities it generates in Mexico are growing far faster than the Mexican government can manage. Crime is so widespread and the corruption it generates is so deeply entrenched among business leaders and government agencies that mass demonstrations demand increasingly basic change just when economic flows steadily worsen Mexico’s social situation.

Globalized capitalism is a chain as strong as its weakest link. The economic crisis that began with the subprime mortgage collapse in the US has since spread via the globalized credit and trade system to the rest of the world. Its terrible economic and social costs and consequences will soon expose the currently weakest links in the chain. Mexico may prove to be one of them.

Rick Wolff is Professor of Economics at University of Massachusetts at Amherst. He is the author of many books and articles, including (with Stephen Resnick) Class Theory and History: Capitalism and Communism in the U.S.S.R. (Routledge, 2002) and (with Stephen Resnick) New Departures in Marxian Theory (Routledge, 2006).

Rick Wolff is Professor of Economics at University of Massachusetts at Amherst. He is the author of many books and articles, including (with Stephen Resnick) Class Theory and History: Capitalism and Communism in the U.S.S.R. (Routledge, 2002) and (with Stephen Resnick) New Departures in Marxian Theory (Routledge, 2006).

|

| Print