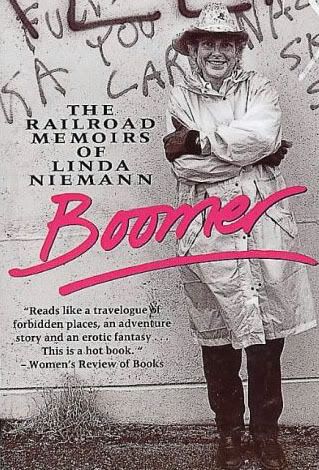

Linda Niemann‘s Boomer: Railroad Memoirs is one of a handful of outstanding books, like Ben Hamper’s Rivethead, that have documented industrial working-class life in the United States, as experienced by the children of the sixties.

Linda Niemann‘s Boomer: Railroad Memoirs is one of a handful of outstanding books, like Ben Hamper’s Rivethead, that have documented industrial working-class life in the United States, as experienced by the children of the sixties.

Boomer vividly illuminates how a generation of railroad workers faced the receding standard of living for workers in the seventies and eighties, in prose that jumps from the page, pulling no punches when it comes to explaining how a collapsing capitalist economy bears down on one’s personal life. Boomer brings to life the unique work experience lived by “rails,” the folks who work the endless river of trains that move the lifeblood of the US economy across the mountains and plains, mostly unseen by the majority of Americans. Boomer also is a documentation of the experience of women “trespassing” in occupations formerly exclusively held by men.

Linda Niemann has generously agreed to be interviewed by Railroad Workers United Co-Chair Jon Flanders, taking time from working on a new book.

Linda, as one of the first women to be hired on the transportation side of the railroad industry, back in 1979, you were one of the female pioneers of that time, breaking down barriers in formerly all male job trusts, not to mention the nepotism traditional in the railroad world. Did you see yourself in that light, as a gate crasher for women?

It was hard not to, since everybody was always throwing out this party line that we should be home cooking or something. I mean, this was 1979. I just thought it was quaint.

Since you ran into a “party line,” did you develop a “party line” verbal response?

Well, there was really no point in arguing with people about anything. . . . I learned that in my marriage. So, I tended to rely on the disgusted look. I did make sure, though, that I did my job. And I found out that if I did the work, the same people that had “objections” would work really well with me. Being an intellectual, it was eye-opening to realize that what people think has little to do with what they do. I just did my job, treated people with respect, and generally got treated the same. That didn’t mean I changed any opinions. I probably didn’t.

I recently watched the movie and read the book about Lois Jensen and some of her female co-workers, who faced horrendous harassment on the job working in the Iron Range of Minnesota. Did you get anything like that kind of treatment on the railroad?

On the railroad, there wasn’t the same level of harassment as in other types of non-traditional jobs. In the first place, we depend on each other for our lives. So that means you depend on me, too. There aren’t any non-critical positions on a crew. Unless you are a real psycho (and I only met one, really), you are not going to mess with someone who can easily get you killed. In general, railroaders are a warm and trustworthy bunch of folks . . . but then you already know that.

In the last several years, we have seen a hiring boom on the railroads as baby boomers retire. What would be the advice you would give a woman today considering railroad work?

Advice for women considering the job would be that if you are reasonably athletic and are not “accident-prone” . . . go for it! Anyone, by the way, can be accident-prone, and if you are you should realize that there are no little accidents on the railroad. It’s dangerous. But for women, traditional trades offer fair wages and a seniority system that works in your favor. If you have the date, you get the job. No politics. Also realize that the railroad will jerk you around and make keeping appointments and commitments to other people difficult. Since women traditionally keep the home running smoothly, ask yourself if you are independent enough to take it on.

Have you had an opportunity to see any changes in the attitudes of young male workers?

Do I notice changes in the young male worker? Can’t really answer that, since I was the baby on the board for 20 years and the only students that showed up were in my last year on the job . . . 1999. Since I was beaucoup years older than them, an old head as it were, they followed me around like ducks. That was a change all right.

What would you say to a young male worker about working for the first time with a woman on the railroad?

Advice to young men working with women for the first time? Don’t hit on them at work, for starters. Treat them like everybody else. I think young people are more into the equality thing than even my generation was. It has taken integration of workplaces for that to happen, and it will take sufficient numbers of women showing up in the freight yard for it to happen there.

Let’s talk a bit about the changes in the nature of the work that you lived through in your twenty years on the rails. You get into that in one of the last chapters of Boomer. Is there still such a thing as the “switchman’s craft” in the age of computers, remote control, and the two person crew?

About the craft, I’m concerned. We learned from the old heads, and it was by watching them over time. They always came up with the slickest moves. Being on the extra board, I was usually in awe of them. When I finally worked a regular job, I started to get it. If you do the same thing every day, you start to do it with less wasted effort. You start shaving minutes off each move. But extra people don’t get that kind of regularity. The craft itself changes, of course, and expertise moves along with it. It takes skill to read a computer print-out. But I’ve been told the company now won’t let people do skilled moves like drops and Dutch drops. Even kicking cars, I was told recently, requires 5 years seniority, so certain aspects of the craft are probably gone forever. Nobody is going to invent the wheel by themselves. You need old heads showing you how to do it safely. Lantern and hand signals are another thing. What if radios fail? You need basics for back-up.

Did you witness any organized resistance to the cuts and changes, either from the ranks or the union leadership?

Did anyone try to oppose the company during all the give-backs? I think the unions fought for better contracts, but no contract was better for me, practically the baby on the system the whole time I was railroading. Since we essentially can’t strike, only 3 days before the government steps in, we need to be the constant squeaky wheel by filing time slips and grievances to see that the company lives up to the contract we both sign. Of course we live up to our part of the deal . . . we have no choice. The company, however, seems to think they have the choice to ignore the sweet deal contract they signed.

You don’t mention attending union meetings in Boomer. Were you able to be active at all, given the nature of your jobs?

Did I go to union meetings? Yes, when I could. On the extra board, it’s hard. It’s also hard to get to meetings when you work in a place like the Bay Area which is so spread out. You are not going to drive over a mountain to go to a meeting, drive back home, and then drive back over the mountain to go to work later. I think internet is a great resource for the unions now. They could have virtual meetings where everyone could participate.

In fact the internet has now made possible phone conferences which can be accessed by cell phone. There are some very interesting implications from this for rail workers.

I’d like to talk about your writing, and I imagine I’m not the only reader of Boomer interested in that. Boomer is not just about railroading. It’s a deeply personal account of questions of sexuality, substance abuse, and problems with relationships. All refracted through the distortion field of the brakeman’s work. In retrospect, do you have any regrets about how much you revealed about your life in Boomer?

The short answer is no. I’ll spare you my rap on how persona is not really you, anyway. I know what you mean by the question. If the reader is going to trust you and see themselves in your story, you have to be as honest as you can be in a memoir. Believe me: I haven’t invented any human desire or behavior. We’re a lot more alike than not. If the reader hasn’t had exactly the same experience I had, they have had some experience that resonates for them when I tell my story.

Did you end up working with people you wrote about? Ben Hamper has a hilarious account in Rivethead about how a newspaper column he wrote bit him in the butt on the job.

Did I work with people I wrote about? Yes! And they came to bookstore readings. Of course, with sensitive material I changed the person’s name and description, so not to do harm. Being in a book is not the same thing as being on the 5 o’clock news. You have become a character and as I said before, it’s not really you, anyway.

How did you manage to recall so much detail concerning the episodes you recount in the book?

How did I remember detail? Wordsworth said imagination is powerful emotions recollected in tranquility. That’s kind of how it works. You store parts of events in your memory. You go back and find these tags and reconstruct a day around them. Is it accurate? For the memoirist the question is really “does it feel accurate?” You are filling in the gaps around a memory hook. You do the best you can.

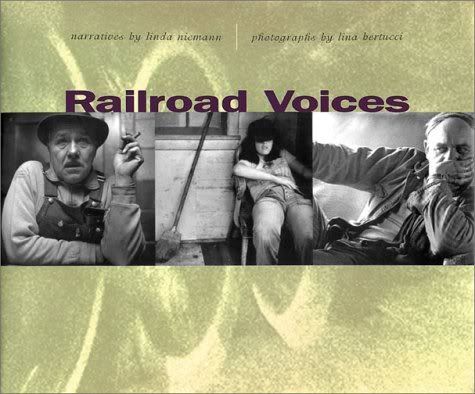

Well, remembering the details of a shove you did 10 years ago is a remarkable feat in my book. And that’s the kind of detailed writing you will find in Boomer and Railroad Voices, the latter I just finished reading this morning.

Well, remembering the details of a shove you did 10 years ago is a remarkable feat in my book. And that’s the kind of detailed writing you will find in Boomer and Railroad Voices, the latter I just finished reading this morning.

I should mention that Railroad Voices is a coffee table style book with the writing mainly by Linda and pictures by Lina Bertucci, another female “brakie” who worked on the Milwaukee Road in the seventies. She has become a well known photographer since. The pictures are stark black and whites, with portraits that remind me a bit of the work of the German photographer August Sander. Believe me, this is a compliment.

You are now working on a new book; could you tell us something about the project, what you are trying to do in relationship to the first two?

The new book, called Railroad Noir, is collaboration with photographer Joel Jensen, whose work is as edgy as mine. Joel’s camera does not turn away from alcoholism, loneliness, desolation, or the beauty of those lonely desolate western places where trains run. We have worked together in Trains Magazine for several years and I wanted to see what our two parallel essays, a literary one and a photographic one, would be like together. My part is a continuation of my railroad story, why I left the railroad after 20 years in 1999 and what led up to that decision. I am also going to go back and talk to new hires about their railroad now, as well as ask the old heads what they think of things. Kind of a dialog between old and new, for the ending of the book. I also want to describe certain craft skills before everyone forgets what they were.

I’ve mentioned Ben Hamper’s Rivethead. Are there other working life memoirs you’ve run across that you would recommend?

The ones I read before writing Boomer were B. Traven’s Death Ship and La Carreta, but any of his novels really take on certain crafts in detail, George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, and Melville’s White Jacket. There’s also Life in the Iron Mills.

Finally Linda, what do you think about the effort to organize the Railroad Workers United Caucus across all the railroad crafts?

As to RWU, I joined as an adjunct member. I think it’s a very good idea to have a forum for discussion. There used to be this cool newsletter out of Roseville called Snakebites. It hasn’t come out in a while, but you would really get the skinny on what was going on at ground level. Very irreverent. Any organizing is good organizing as far as I’m concerned. The company is pretty monolithic and doesn’t respond to anything but the bottom line. Workers have to formulate what their interests are before they can work for them. Right now it seems like the traditional unions are on the ropes, defending disciplinary cases. They are not in a position to move forward.

This interview first appeared in the Web site of Railroad Workers United.

|

| Print