| “Our community is expanding: MRZine viewers have increased in number, as have the readers of our editions published outside the United States and in languages other than English. We sense a sharp increase in interest in our perspective and its history. Many in our community have made use of the MR archive we put online, an archive we plan to make fully searchable in the coming years. Of course much of the increased interest is from cash-strapped students in the metropolis, and from some of the poorest countries on the globe. For those of us able to help this is an extra challenge. We can together keep up the fight to expand the space of socialist sanity in the global flood of the Murdoch-poisoned media. Please write us a check today.” — John Bellamy Foster

To donate by credit card on the phone, call toll-free: You can also donate by clicking on the PayPal logo below: If you would rather donate via check, please make it out to the Monthly Review Foundation and mail it to:

Donations are tax deductible. Thank you! |

Lalgarh was an obscure place in West Midnapore district of West Bengal (India). Before November 2008, it was just another village, 42 kilometers from the Midnapore railway station. Not any more. It is the centre of the movement of people who constitute almost 10% of the population of India. Lalgarh is now an icon of the defiance of the adivasi (tribal/indigenous population) against their history of discrimination and oppression.

The Shalbani land mine explosion on 2nd November 2008, which was targeted at the Chief Minister’s convoy returning from the proposed site of Jindal Steel Plant, resulted in hyperactivity of the police, who immediately had to prove their proactive nature by identifying the ‘culprits,’ or rather scapegoats. As always they chose easy targets, tribal people from Lalgarh.

There is no map to Lalgarh, at least none easily available. The most detailed map shows a narrow road from Midnapore Station, which abruptly ends somewhere near Pirahkata. The road from Pirahkata to Lalgarh is well made but scantily used. The road is of no use to the indigenous population who possess no cars. Even motorbikes are a rarity among them, and their primary mode of transport is bullock carts, cycles or walking. So the quality of this road is not for the locals to appreciate. Its sole purpose is the quick transportation of police and para-military. This in fact sums up the direction of development in the majority of such areas.

There is no map to Lalgarh, at least none easily available. The most detailed map shows a narrow road from Midnapore Station, which abruptly ends somewhere near Pirahkata. The road from Pirahkata to Lalgarh is well made but scantily used. The road is of no use to the indigenous population who possess no cars. Even motorbikes are a rarity among them, and their primary mode of transport is bullock carts, cycles or walking. So the quality of this road is not for the locals to appreciate. Its sole purpose is the quick transportation of police and para-military. This in fact sums up the direction of development in the majority of such areas.  The black pitch road on the red soil surrounded by forests is most picturesque. The tranquility of the place was, until recently, disturbed every now and then by rumbling police jeeps and vans which would enter villages routinely and pick up adivasi for questioning. Often such questioning was accompanied by a generous dose of sadistic torture, both physical and psychological. It is most common to come across men and women of the region who have been detained and tortured apparently for no concrete reason, without any legal charge sheet produced. Detention often extends to three months on the base of mere speculation. People could not venture out of their houses after dark. The local police have even targeted some people whom they would repeatedly pick up for interrogation. A few conversations with the locals are enough to reveal a completely different world where not a day goes by without terror. The entire system at every level is bent on keeping them in such a state of constant fear that they would not even dream of making demands of development and all they wish for is a day without torture and police oppression.

The black pitch road on the red soil surrounded by forests is most picturesque. The tranquility of the place was, until recently, disturbed every now and then by rumbling police jeeps and vans which would enter villages routinely and pick up adivasi for questioning. Often such questioning was accompanied by a generous dose of sadistic torture, both physical and psychological. It is most common to come across men and women of the region who have been detained and tortured apparently for no concrete reason, without any legal charge sheet produced. Detention often extends to three months on the base of mere speculation. People could not venture out of their houses after dark. The local police have even targeted some people whom they would repeatedly pick up for interrogation. A few conversations with the locals are enough to reveal a completely different world where not a day goes by without terror. The entire system at every level is bent on keeping them in such a state of constant fear that they would not even dream of making demands of development and all they wish for is a day without torture and police oppression.

Just after the Shalboni incident, the police of the Lalgarh and Ramgarh police stations led a joint operation on 5th November 2008, into the villages of Choto Pelia, Boro Pelia, Bashber and Kata Pahari. These are small villages at least two to six miles from each other, surrounded by forests and interconnected by narrow roads. They are thus easy targets for the police, where they can carry on their torturous interrogations in isolation without the news quickly leaking to surrounding villages. In Choto Pelia the police forced their way into houses and tortured and beat up people in their usual manner. According to one person, “We know the police from the way they knock at the door, just one long and loud knock and then they break in with heavy kicks. They do not even wait for anyone to open the door.” In one such house the family was having a guest, a relative from a nearby village who was helping to stack up the paddy from the fields. The police at once singled him out, labeling him as an ‘outsider’ who has come to carry out the ‘Shalboni Landmine Operation’. When the police tried to take him away, the women from the family tried pleading with the police. They pointed out that he was a guest and a relative and it was a disgrace to take him away in that manner. The police were in no mood to listen and thrashed them with the butt of their guns. One woman was hit right in the eye. She fell unconscious, her eye damaged permanently. Their guest was dragged away by four constables holding his hands and legs and thrown into the police van. On the same night, another police patrol came across four boys, all school students of classes eight to ten. They were returning to their homes in Bashber after a programme of Baul (folk) songs in Katapahari some 2 miles away. They were picked up without any questioning. “They never asked us a question, they just asked us to step into the van. We had no choice,” remembered one of the students. In the police station, as their names and fathers’ names were taken down, the police learnt that one boy had a father working in the army, and he was released at once. It was through him that the village came to know of the whereabouts of the other boys. The headmaster of Katapahari High School was detained on grounds of being a Maoist conspirator and hatching plans with his students. The police were working towards putting forth a good, dramatic and flawless lie that the press would readily endorse. Further detention and torture continued throughout the night. These incidents triggered the mass protests but are by no means the sole reason behind it. These were just the sparks to the gunpowder.

Just after the Shalboni incident, the police of the Lalgarh and Ramgarh police stations led a joint operation on 5th November 2008, into the villages of Choto Pelia, Boro Pelia, Bashber and Kata Pahari. These are small villages at least two to six miles from each other, surrounded by forests and interconnected by narrow roads. They are thus easy targets for the police, where they can carry on their torturous interrogations in isolation without the news quickly leaking to surrounding villages. In Choto Pelia the police forced their way into houses and tortured and beat up people in their usual manner. According to one person, “We know the police from the way they knock at the door, just one long and loud knock and then they break in with heavy kicks. They do not even wait for anyone to open the door.” In one such house the family was having a guest, a relative from a nearby village who was helping to stack up the paddy from the fields. The police at once singled him out, labeling him as an ‘outsider’ who has come to carry out the ‘Shalboni Landmine Operation’. When the police tried to take him away, the women from the family tried pleading with the police. They pointed out that he was a guest and a relative and it was a disgrace to take him away in that manner. The police were in no mood to listen and thrashed them with the butt of their guns. One woman was hit right in the eye. She fell unconscious, her eye damaged permanently. Their guest was dragged away by four constables holding his hands and legs and thrown into the police van. On the same night, another police patrol came across four boys, all school students of classes eight to ten. They were returning to their homes in Bashber after a programme of Baul (folk) songs in Katapahari some 2 miles away. They were picked up without any questioning. “They never asked us a question, they just asked us to step into the van. We had no choice,” remembered one of the students. In the police station, as their names and fathers’ names were taken down, the police learnt that one boy had a father working in the army, and he was released at once. It was through him that the village came to know of the whereabouts of the other boys. The headmaster of Katapahari High School was detained on grounds of being a Maoist conspirator and hatching plans with his students. The police were working towards putting forth a good, dramatic and flawless lie that the press would readily endorse. Further detention and torture continued throughout the night. These incidents triggered the mass protests but are by no means the sole reason behind it. These were just the sparks to the gunpowder.

The list of deprivations and oppressions of the adivasis is a never ending one, and the government and the police took it for granted that these simple rustic peace-loving people had almost learnt to live with it. The police were too confident that their detentions would go unchallenged as always, especially when the adivasis of Lalgarh had no backing from mainstream parties — neither the Communist Party of India (Marxist) [CPI (M)] that governs West Bengal, nor the Congress, nor the Trinamool Congress, longtime ally of the Hindutva fascists. Remarkably, but not surprisingly, police never found it necessary to carry out investigations in the villages surrounding the location of the incident; they did not question even those peasants from whose fields the kilometer-long wire used to trigger the mine had been dug up. The simple reason for that is that the village and the region is politically a CPI (M) stronghold, and the party leaders did not want the police to harass their supporters.

Most adivasi of Lalgarh would point out that police repression had steadily increased since 1998, the year that marked a sudden spurt in Maoist activities in the tribal belt. People were picked up from their homes by the police, and often relatives were asked to sign papers which said that the person arrested was found in some forest and certain guns and ammunition were recovered from them. Refusal to sign would result in inhuman torture and prolonged detention without the arrest being acknowledged officially; signing the paper would mean lesser tortures but also a never-ending litigation. By 2008 there was hardly a single home in the tribal belt of West Bengal where police had not picked up and tortured a resident for being a ‘Maoist’ or a sympathizer.

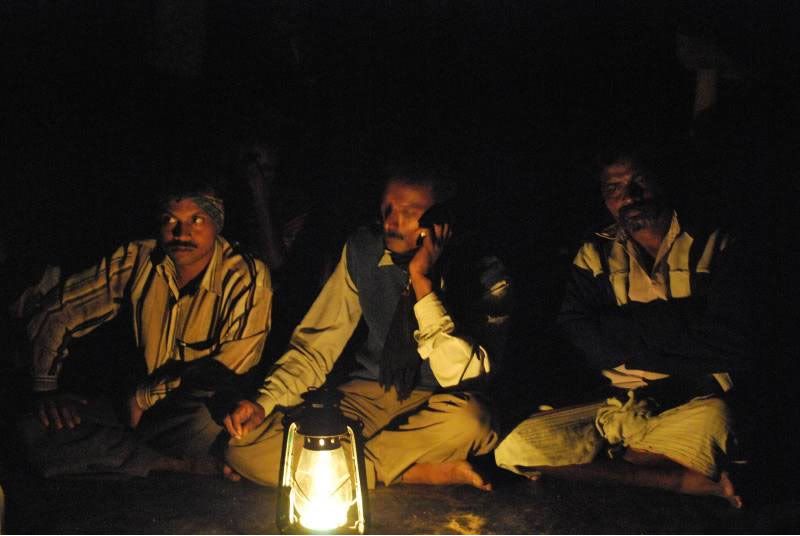

The funds allotted to development of adivasis are regularly siphoned away by Panchayet [local government] leaders while the only visible development is more and more police camps, modern weapons and better-fortified police stations. Even as crores are being spent on modernizing the Lalgarh police stations, no house in the villages around has access to electricity, schools are but buildings without teachers, irrigation canals are perennially dry and the only toilets are the fields and forests. The majority of houses are still of mud and thatched roof of dry leaves while CPI (M) leaders have grossly misdirected funds allocated for Indira Awaas Yojna. According to IAY, money in installments can be provided to rural people living below poverty line (preference being given to members of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes) to build proper houses, with the cost shared between State and Central government. Funds are distributed by local Panchayets, and people who truly need the benefits have hardly heard of the scheme, while sons and daughters of local leaders got houses. Health Centers in the villages are at best occasionally visited by doctors and medicines are never available there.

In spite of all the deprivation and torture, only small, uncoordinated bursts of protest occurred, which were easily pacified or repressed. Often local leadership were bought and made to give pacifying statements after closed-door meetings. The leaders took the decision for the entire community. But the post-Shalboni protests were different — they had no leadership who could decide for everyone. The adivasis had representatives who only communicated the decision of the entire community rather than took decisions on everyone’s behalf.

On 6th November, adivasis gathered and moved to the Lalgarh police station and demanded immediate and unconditional release of all villagers detained without any ground, including the three boys. Looking at the unprecedented mobilization of the adivasis, the police well understood the gravity of the situation and started making false promises to pacify the crowds and buy time. But the situation grew tenser by the hour and soon support from other adivasi villages started pouring in. After night-long assurance that the boys would be soon released, in the morning, seeing that the mobilization had only grown yet larger, the police had to concede that the boys were never in the local police station but had been transferred to Midnapore Police Station. The adivasis could not be pacified with this — they understood clearly that the words of assurance from the police could not be counted upon for release of their people, and a full-fledged movement needed to be launched. It was made clear to the police that they were not welcome in the villages any more. They decided to organize themselves and move for a permanent solution to this mindless police oppression.

The Lalgarh adivasis sat together in lengthy meetings and chalked out a proper plan to carry forth the movement. They decided to go around the existing mainstream political parties and float a forum of their own. This resulted in almost unanimous support of all adivasi sections towards the movement. They also decided upon an 11-point demand. The leadership emerged from within the people. But they insisted upon calling themselves a committee of the people, rather than leadership. And truly they have acted as spokespersons of the villages. Every village has chosen a 10-member committee of 5 men and 5 women.

The Lalgarh adivasis sat together in lengthy meetings and chalked out a proper plan to carry forth the movement. They decided to go around the existing mainstream political parties and float a forum of their own. This resulted in almost unanimous support of all adivasi sections towards the movement. They also decided upon an 11-point demand. The leadership emerged from within the people. But they insisted upon calling themselves a committee of the people, rather than leadership. And truly they have acted as spokespersons of the villages. Every village has chosen a 10-member committee of 5 men and 5 women.  The participation of youth in these committees is truly overwhelming, as is their participation in the movement. This development and practice of participatory democracy is perhaps the most distinguishing and positive feature in these events. And this is the main point of concern for the government and the mainstream parties. Furthermore, these committees have specialized work allotted to the members, like communicating to journalists, maintaining contact with outsiders, communicating within the village, keeping in touch with far-off villages where the movement has spread. Within weeks of the movement, results started to show. The movement spread across other districts like Bankura, Birbhum, Puruliya and even North Bengal. Everywhere the character was similar, the mainstream parties dissolved away and committees sprung up. And everywhere the adivasis took measures to keep out the police: they barricaded the roads with felled trees and cut trenches across roads to prevent quick mobilization of reinforced troops.

The participation of youth in these committees is truly overwhelming, as is their participation in the movement. This development and practice of participatory democracy is perhaps the most distinguishing and positive feature in these events. And this is the main point of concern for the government and the mainstream parties. Furthermore, these committees have specialized work allotted to the members, like communicating to journalists, maintaining contact with outsiders, communicating within the village, keeping in touch with far-off villages where the movement has spread. Within weeks of the movement, results started to show. The movement spread across other districts like Bankura, Birbhum, Puruliya and even North Bengal. Everywhere the character was similar, the mainstream parties dissolved away and committees sprung up. And everywhere the adivasis took measures to keep out the police: they barricaded the roads with felled trees and cut trenches across roads to prevent quick mobilization of reinforced troops.

In every aspect, the movement has shown that it has not ignored the lessons of Nandigram and Singur and is in fact a level above. Without spilling a drop of blood it has spread so far that it really inspires many thoughts. All these years, in spite of their regions being neglected and kept underdeveloped and in darkness, the adivasis, who are peace-loving people, have never protested . . . until now. Gradually this movement is taking a rather novel shape. The government is at a loss to counter what has captured the imagination of such a large section of the population across such vast region in such short time. Unlike Nandigram, it is too large to be surrounded by CPI (M) mercenaries. And the adivasis are too self-sufficient to be starved out. These people need little to sustain themselves and they themselves produce most of it. The roads that they have blocked are preventing police vans only; they never needed these roads and hardly ever use them. The government and the ruling party don’t know what to do as their meager presence within the adivasi communities suddenly evaporated and information flow from the adivasi belt has stopped completely. Moreover, unlike in Singur or Nandigram, they had no ready group of leaders who would be willing to negotiate or bargain behind closed doors, keeping the movement on hold. In fact, the adivasis have welcomed any representative of government to discuss their demands, but only at their villages. In total disregard and disrespect of where the adivasi people live, however, they say, ‘how can negotiation and discussion take place in jungle’.

The government tried to create confusion by roping in the upper ‘creamy’ section of the traditional adivasi leaders, who posed as the leadership of the movement. These emerged out of nowhere, completely ignorant of the ground situation, attended a meeting with the government officials and came out and declared before the press that all their demands had been met and they were thereby calling off the movement. Initially this caused some misunderstanding amongst the adivasi communities, but they soon got the crux of the matter and these traditional respected elders of the adivasi society were boycotted and asked to stay out of the movement.

The ruling party was and still is in a state of constant denial of the true nature of the movement and at rallies and meetings they utter less than confident phrases like ‘our adivasi brothers are being misled by Maoists’, ‘it is a counter revolutionary force’, ‘imperialist funded conspiracy’ and so on. At one meeting the State Secretary of the CPI (M) went as far as to state that at least in West Bengal the adivasis are in better conditions than their Jharkhand counterparts, at least the West Bengal government hasn’t ordered them shot as the Babu Lal Marandi government did in Jharkhand. Mr. Bose perhaps expected his ‘adivasi brothers’ to be thankful for that and call off their movement.

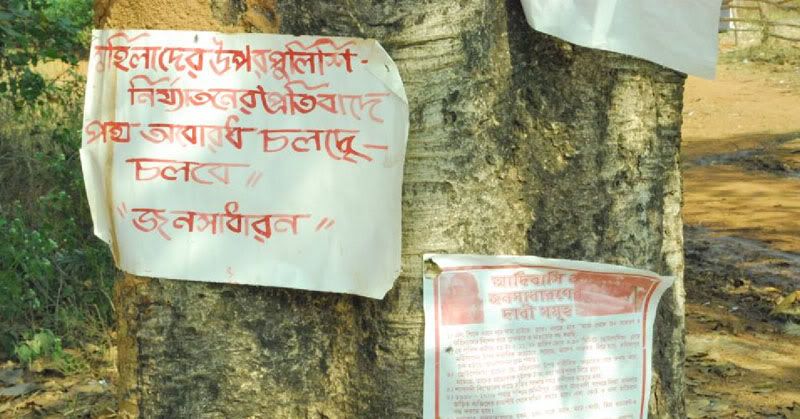

The Lalgarh movement has matured and is preparing for a long drawn-out and sustainable movement, beyond mere blockades, demonstrations and rallies. They are coordinating their moves with far-off villages, communicating strategies. They are campaigning, talking to people and press, writing posters, distributing leaflets and trying to take their demands to the heart of Calcutta. All their campaign and communication are on behalf of ‘the people’ or ‘the people’s committee against police atrocities’. They understand very well that the elite Bengali intelligentsia will not act as sympathetically to the movement explicitly of the indigenous tribal masses, and they are prepared to do without it. But they have decided that they won’t fade out without being heard.

The demands of the adivasis are not revolutionary but for a simple life without unnecessary interference. The core demand is their right to decide for themselves, to preserve their culture. Indeed their movement has not hampered the normalcy of their lives. Their blockades are lifted from time to time to allow passage of paddy-filled bullock carts from fields to villages, which is a most important activity during this season of harvest. They allow and invite representatives of all press, civil society organizations and even general citizens to come and move around their villages. They have successfully prevented the uninvited patrol of the police jeeps, and the villages are most peaceful these days. The state of constant fear that they had to live with is gone. The only hardship they have had to accept is carrying away seriously ill patients to town. They never had any proper health center anyway, for any serious ailment they had to travel to town, now they only have to take a longer route.

In their path towards a sustained movement, they meet often within and amongst villages. Each village committee has two persons who should be available at every meeting. The meetings are in local languages and are often lengthy and attended by many. In late night discussions among the committee members, it’s not unusual to find the youth in early twenties doing most of the talking. They even mention ‘class struggle’, ‘imperialism’, ‘cultural hegemony’ rather lucidly, and in their own way. They admit openly their failure to spread their movement and thoughts in all ‘fronts’. To a question like what will happen if paramilitary is deployed to crush the movement, they smile and reply that they will resist though they will eventually fail, many will perish but not all. They quickly refer to Iraq, where many were killed but the protest is still on. They also point out that the movement began without a single act of violence, and that they want none, so they prefer the path of non-violent mass movement unless they have to defend themselves from armed attacks. To ask these people who are protesting the police excesses and demanding a normal life whether they are all ‘Maoists’ is redundant.

Koustav De is an activist in India.