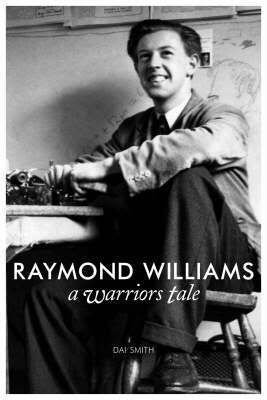

This year sees the 20th anniversary of the death of Raymond Williams, one of the towering socialist thinkers of the past century. A superb biography — Raymond Williams: A Warrior’s Tale — has just been published by Dai Smith. He charts Williams’s passage from the Welsh border country, where his father was a railway signalman, to Cambridge and then adult education, a vocation he chose, along with New Left colleagues Richard Hoggart and EP Thompson, for political motives. In a rare moment of disillusion, he told me that the difference between teaching adults and students in the 1950s was like “teaching doctors’ daughters rather than doctors’ sons”. But he never doubted that any Labour government worth its salt would invest massively in “institutions of popular culture and education”, and lambasted them all, from Attlee to Wilson, for failing to do so.

This year sees the 20th anniversary of the death of Raymond Williams, one of the towering socialist thinkers of the past century. A superb biography — Raymond Williams: A Warrior’s Tale — has just been published by Dai Smith. He charts Williams’s passage from the Welsh border country, where his father was a railway signalman, to Cambridge and then adult education, a vocation he chose, along with New Left colleagues Richard Hoggart and EP Thompson, for political motives. In a rare moment of disillusion, he told me that the difference between teaching adults and students in the 1950s was like “teaching doctors’ daughters rather than doctors’ sons”. But he never doubted that any Labour government worth its salt would invest massively in “institutions of popular culture and education”, and lambasted them all, from Attlee to Wilson, for failing to do so.

“Culture is ordinary,” Williams wrote in a pioneering essay, and his own life was a case in point. He saw his transition from Black Mountains to Cambridge spires as in no sense untypical. Right to the end, he regarded the politically conscious rural community in which he was reared, with its neighbourliness and cooperative spirit, as far more of a genuine culture than the Cambridge in which he held a professorial chair and that he once acidly described as “one of the rudest places on earth”. Working-class Britain may not have produced its quota of Miltons and Jane Austens; but in Williams’s view it had given birth to a culture that was at least as valuable: the dearly won institutions of the labour, union and cooperative movements.

Since Williams’s death in 1988, culture, one might claim, has become more ordinary than ever. Not in the sense that Milton is sold in supermarkets, though Austen has been sprung from college libraries into film and television. In the teeth of the Jeremiahs, Williams never ceased to argue for the progressive potential of the media. But he believed that these vital modes of speaking to each other should be wrested back from the cynics who exploited them for private gain. His prescription for dealing with the Murdochs of this world was bracingly free of his usual circumspection: “These men must be run out.”

The real sense in which culture since Williams’s death has become more ordinary has little to do with Dante or Mozart. One of Williams’s key moves was to insist that culture meant not just eminent works of art, but a whole way of life in common; and culture in this sense — language, inheritance, identity, religion — has become important enough to kill for. Dante and Mozart may be elitist, but they have never blown the limbs off small children.

The political currents that topped the global agenda in the late 20th century — revolutionary nationalism, feminism and ethnic struggle — place culture at their heart. Language, identity and forms of life are the terms in which political demands are shaped and voiced. In this sense, culture has become part of the problem rather than the solution, as it was for Matthew Arnold and FR Leavis. In traditional forms of political conflict, working people have proved most inspired when what was at stake was not just a living wage but (like the mining communities) the defence of a way of life. The political demand our rulers find hardest to beat is one that is cultural and material.

Ever since the early 19th century, culture or civilisation has been the opposite of barbarism. Behind this opposition lay a kind of narrative: first you had barbarism, then civilisation was dredged out of its murky depths. Radical thinkers, by contrast, have always seen barbarism and civilisation as synchronous. This is what the German Marxist Walter Benjamin had in mind when he declared that “every document of civilisation is at the same time a record of barbarism”. For every cathedral, a pit of bones; for every work of art, the mass labour that granted the artist the resources to create it. Civilisation needs to be wrested from nature by violence, but the violence lives on in the coercion used to protect civilisation — a coercion known among other things as the political state.

These days the conflict between civilisation and barbarism has taken an ominous turn. We face a conflict between civilisation and culture, which used to be on the same side. Civilisation means rational reflection, material wellbeing, individual autonomy and ironic self-doubt; culture means a form of life that is customary, collective, passionate, spontaneous, unreflective and arational. It is no surprise, then, to find that we have civilisation whereas they have culture. Culture is the new barbarism. The contrast between west and east is being mapped on a new axis.

The problem is that civilisation needs culture even if it feels superior to it. Its own political authority will not operate unless it can bed itself down in a specific way of life. Men and women do not easily submit to a power that does not weave itself into the texture of their daily existence — one reason why culture remains so politically vital. Civilisation cannot get on with culture, and it cannot get on without it. We can be sure that Williams would have brought his wisdom to bear on this conundrum.

Terry Eagleton is a literary theorist and critic. He is the author of more than forty books, the most recent of which is Trouble with Strangers: A Study of Ethics. This article was first published by the Guardian under the title of “Culture Conundrum” on 21 May 2008; it is reproduced here for educational purposes.