Analytical Monthly Review, published in Kharagpur, West Bengal, India, is a sister edition of Monthly Review. Its June 2009 issue features the following editorial. — Ed.

The dire consequences of human induced climate change are now most often presented as facing us in the near future. We suggest that the future, as far as the lower Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta is concerned, has arrived.

Even a full fortnight after Cyclone Aila ravaged the Sunderbans, no one — not the government, nor relief workers — knew exactly what it is like in the devastated villages. The exact death toll due to the cyclone itself as well as due to the epidemic aftermath of the cyclone is yet to be gauged. Nor is this in any sense something unexpected. The Sunderban region is well described in government’s official portal under the subheading “Disaster Management Plan” as — “Being a part of the active delta of the Ganga, South 24-Parganas is basically a district of islands interspersed by many streams and a maze of innumerable distributaries and fearfully wide tidal creeks. It is very sad to admit that to most of these islanders’ wide roads, safe water transport, safe jetties or bridges, electricity or telephones are till date — distant dreams. They do not have many strong and high buildings that can be used as shelters during large scale disasters and they hardly have any large vessel to help large scale evacuation.”

As per 2001 Census, the total population of the region was about 37.56 lakh. Only 3% were in part-time or marginal employment and 27% in main employment categories. Such employment as exists is limited to agriculture as cultivators and as laborers, and as fishermen. Sunderban was declared a World Heritage Site in 1987 and a Biosphere Reserve in 1989. Thirteen of its densely populated riverine blocks are nearly always under threat from Nor’westers, bay cyclones, tidal surges and change in courses of numerous distributaries. The region never took a place in the so-called “development map” except once for the irresponsible proposal of a nuclear power plant — abandoned in the face of protest — and an occasional mention of tourism development.

Now in the wake of devastation by the cyclone, some 400km of 3500km embankment has been wiped away, and 900km is damaged and could give way at any moment. Extensive areas of the Sunderbans like Sandeshkhali, Jogeshganj and Hemnagar which are naturally below the water-level are inundated. Ponds have turned saline. Stagnant water has become contaminated with floating carcasses of cattle and rotting fish. Affected communities, farmers and fishermen, have lost their livelihoods and home. Rice paddy fields have been contaminated with saline water, tens of thousands of poultry and livestock have been killed and fishing boats destroyed. The residents have been forced to drink contaminated water due to an acute shortage of potable water. Enteric diseases and diarrhea are spreading fast and threaten an epidemic. Reports of death due to enteric diseases have already been received. Medical help is yet to reach remote villages. Exodus of climate refugees has already started in search of work, food and shelter. There is no dispute regarding the immediate need of a large-scale rescue, relief and rehabilitation program. A fraction of that is yet to be achieved. Allegation and counter allegation is underway regarding the maintenance of embankments, lack of co-ordination in the distribution of relief, unpreparedness of the administration, bureaucratic way of distribution of relief, casual attitude of the government to warnings given by the meteorological department, and so on. The parliamentary political parties appear to be primarily concerned to consolidate their vote-banks through control of the distribution of relief.

But the question remains whether the death and destruction in the wake of the storm was unexpected. The answer is ‘No’. Sugata Hazra, director of Jadavpur University’s School of Oceanographic Studies in a article in Down to Earth (January 15, 2007) put it in plain language — the Sunderbans “is a unique case where the most socially and economically vulnerable population . . . lives on most vulnerable land”. His findings were summarised as follows:

Hazra and his team of researchers, who have studied the region for several years, compiled a study — ‘Preparatory Assessment of Vulnerability of the Ecologically Sensitive Sunderban Island System, West Bengal, in the Perpective of Climate Change’ — in 2003 in which they say an annual 3.14 mm rise in sea level due to climate change is partly responsible for eating away these islands on the southern fringes of the Sunderbans. The higher than average rise in sea level (which is about 2.0 mm annually worldwide) is because of land subsidence (the caving in or sinking of an area of land through tidal erosion) which is typical of deltaic regions, Hazra says. . . . The scientists, through statistical analysis of erosion and accretion rates of the Sunderbans islands and mathematical correlation studies, have found a link between relative rise in sea level and higher coastal erosion rates in the region. Based on this, they have identified the 12 southernmost islands in the region (including Ghoramara) as “most vulnerable in terms of coastal erosion, submergence and flooding’.

Two islands — Lohachara and Suparibhanga — have already been submerged. Another, Ghoramara, has lost 9/10ths of its original landmass of 9,600 acres. Oceanographers and environmental scientists, including those involved with the important 2007 report of the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), confirm the worst fears of the most vulnerable of all those at risk — the 70,000 inhabitants of at least 14 of the most low-lying islands that are a part of the Sunderbans delta. The rising waters of the Bay of Bengal will push the level of the tides, thus exerting greater pressure on the embankments. And sooner rather than later, these would start crumbling, allowing saline waters to surge in and flood the islands, rendering uncultivable the thousands of acres of farmland that presently sustain the islanders. To compound the imminent threat, melting of Himalayan glaciers shall cause a decrease in the flow of fresh water into the delta, raising the danger of increased salinity progressively further to the north. The fate of those in the most low-lying districts is tomorrow’s reality for crores.

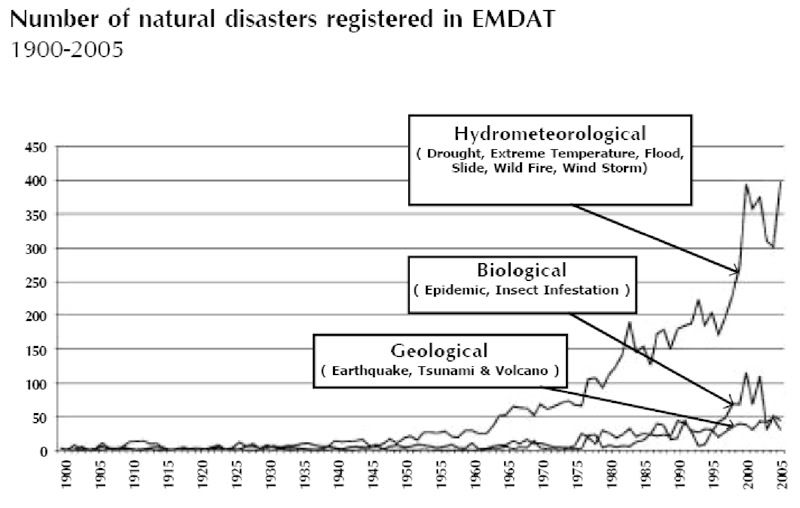

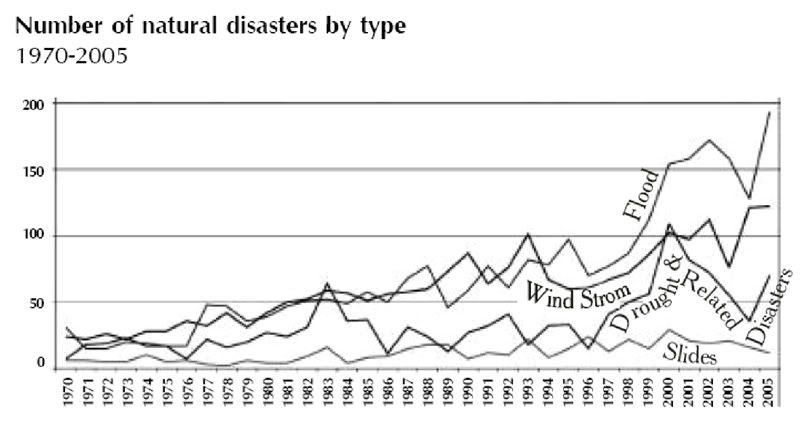

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported in August 2000 that the world’s oceans were warming much faster than anticipated, contributing to sea level rise and global climate change. Over the past several decades the world ocean has warmed by 0.3 degrees Centigrade, representing a huge increase in the heat content of the ocean. Experts say global warming raises atmospheric temperatures, which in turn, warms the world’s oceans. Heat makes water molecules expand — called thermal expansion — causing sea levels to rise. The role of accelerating climate change in the making of natural disasters is quite evident from the following charts (from Guha-Sapir, Hargitt and Hoyois, Thirty Years of Natural Disasters 1974-2003: The Numbers (UCL Presses, Universitaires de Louvain, 2004)), showing a sudden dramatic rise in “hydrometeorological” (i.e., floods, windstorms, droughts, slides) disasters in the two most recent decades:

It is thus the combination of a rising sea level and a sharply increased prevalence of storms that has put an ever-increasing portion of the lower Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta at risk.

There should no longer be any question as to the causes and consequences of the process. Energy intensive industrialisation in the core countries (and more recently in China) has led to climate change that is already irreversible. Yet the consequent disaster shall fall primarily on populations in the periphery that did not benefit from energy intensive industrialisation, but rather paid for it by their own exploitation and immiseration. While the Dutch calmly devise for their lowland paradise immensely expensive technological protections from the combination of storms and a rising sea, for Indonesians whose exploitation made Dutch wealth possible such an option is immensely more difficult.

Cyclone Aila, not an extraordinary storm but one with extraordinary consequences, tells us that the future has arrived. We will not be protected from the oncoming environmental disaster by any action (such as the Kyoto treaty or its successors) of the richest countries of the earth, yet less their charity. Our technology and science can provide; India has already established a research station in Antarctica and there is even talk of moon missions. The vast resources today mobilized for the external and internal military forces hint at what might be available for lifesaving purposes in a different, rational and better society. The danger to the vast community who reside in the lower Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta is manifest, though only present to media consciousness in moments of newsworthy disasters. We must force the issue to the front of the agenda in our own communities.

For all who watch, or read of, the plight of our brothers and sisters of the Sunderbans, it is well to recall what Marx had to say to his readers in largely pre-industrial Germany who questioned why he had focused on British economic history. De te fabula narratur (“this is your story”) was his reply.