Analytical Monthly Review, published in Kharagpur, West Bengal, India, is a sister edition of Monthly Review. Its October 2013 issue features the following editorial. — Ed.

When the last of the British army departed on February 28, 1948, they marched to the Gateway of India — not yet obstructed by yellow concrete barricades — and played their regimental march. When the British army surrendered to the allied rebel Continental army and the French army and navy at Yorktown, Virginia on October 19, 1781, the tradition is that the British fifes (bashis) and drums played a popular marching tune of the day, “The World Turned Upside Down”.

The imperial point of view persists, even after almost a century has passed since the Great October Revolution in Russia gave the rest of us a different — turned right side up, so to speak — perspective. Among the tasks of critical left media is the endless process of reversing the perspective of stories from the mass media; another way of putting it is “ideology critique”. A clear instance is the “Global Competitiveness Report 2013-2014” of the World Economic Forum, the Swiss organisation that every year gathers some 2500 of the richest and most powerful people in the world (“extremely narrow highly privileged elites” in the words of Noam Chomsky) at the Alpine resort town of Davos. With their various “partners” — in India the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), in Bangladesh the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), in Nepal the Centre for Economic Development and Administration (CEDA) — the World Economic Forum annually produces a well-funded slick publication ranking the nations of the world from best to worst.

Our business media then spews this ideology of the “Masters of the Universe” back upon us in the form of revealed truth. From the Economic Times on October 5, 2013: “in the ‘Global Competitiveness Report (GCR) 2013’, on the global index of ‘trade tariffs (tradeweighted average tariff rate)’ India ranks 128, and on ‘prevalence of trade barriers’ (health and product standards, technical and labelling requirements etc), India ranks 61, among 148 countries. Thus, there is a need to improve in these areas.” From Livemint on October 4, 2013: “India ranks 104 in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index for burdensome bureaucracy, while China is ranked 14. India’s overall position in the competitiveness index fell to 60 in the 2013 report. The nation has lost 15 places since 2006.” Again the Economic Times on October 1, 2013: “The [Global Competitiveness] report notes the long time it takes to set up business in India and cites relatively high tax rate as a proportion of profit, higher trade tariffs and high proportion of imports to GDP as factors lowering goods market efficiency. Labour market efficiency is impeded by stringent labour laws. . . . The report makes several recommendations to improve GC, such as avoiding complacency, ensuring investment-and employment-friendly environment, fostering innovation and broad-based structural reforms. . . . Hence, India urgently needs measures to improve the business environment for domestic and foreign investors that will help improve macroeconomic indicators. . . .”

What is good for the tens of crores turns out to be bad for the tens of thousands: health and product standards are “trade barriers” administered by “burdensome bureaucracy”, and taxes on profits lower “market efficiency”. No surprise there. But the ideological heart of the “Global Competitiveness Report” is its discussion of labour market efficiency and labour management relations, and deserves a closer examination.

At about the same time as the “Global Competitiveness Report” made its way into our media, reports appeared on the scandalous situation of migrant labour in Qatar. More than ninety percent of the labour force in the oil-rich emirate are immigrant, and the largest number are from Nepal. Over one hundred thousand Nepalis left for Qatar in the past year, and the Nepal legation in Qatar has estimated that there are more than five lakh Nepali nationals in the country.

The choice of Qatar as the location of the 2022 World Cup spurred a vast building program and increased the demand for immigrant labour. Reports of horrendous work conditions and suspicious deaths have appeared in the Nepali press in the last several years, but poverty and the absence of work in Nepal — and the influence of wealthy unscrupulous emigration brokers — maintained the flow of work-seeking emigrants.

Only when a report “Revealed: Qatar’s World Cup ‘Slaves'” appeared in the influential Guardian newspaper on September 25, 2013, has the issue been reported in our press. The Guardian investigation “found evidence to suggest that thousands of Nepalese, who make up the single largest group of labourers in Qatar, face exploitation and abuses that amount to modern-day slavery, as defined by the International Labour Organisation. . . .” Nepalis in Qatar told the Guardian that they “have not been paid for months and have had their salaries retained to stop them running away.” Others “say employers routinely confiscate passports and refuse to issue ID cards, in effect reducing them to the status of illegal aliens” and that “they have been denied access to free drinking water in the desert heat.”

Yet worse, it appeared that Nepalis — even though by and large healthy young men — were dying in Qatar at the rate of one a day, primarily of supposed “heart attacks”. The Guardian investigated one case in detail:

Ganesh Bishwakarma was one such worker. For Ganesh, Qatar was an oasis in the desert, a promised land where he could work his way out of the acute poverty that had trapped his family in Nepal’s rural Dang district for generations. Like many others in his village he had met the recruitment agents who promised well paid work and the opportunity to provide for his family. He left pledging to come back and build his mother a beautiful house.

He did return — after only two months and in a coffin. He was 16.

“We didn’t think he would die like this,” said his grandmother, Motikala. “We didn’t think we would be crying like this.”

. . .

At 16, Ganesh was too young to have legally migrated for work, but that did not stop a local recruitment broker arranging a fake passport stating he was 20. The broker charged an extortionate fee for a cleaning job in Qatar — far in excess of the legal limit set by the Nepalese government — leaving the boy and his family with a 150,000-rupee (£940) recruitment debt that he promised to pay back at an interest rate of 36%.

. . .

Ganesh’s family was told the boy died of a cardiac arrest weeks after he arrived in Qatar. It is something the family finds hard to accept. “This son of mine was strong. He didn’t even have a cough,” said his father, Tilak Bahadur. “He went abroad and died unexpectedly. Was it the climate or something else?”

The Nepali ambassador to Qatar, Maya Kumari Sharma, in June of this year called Qatar “an open jail”. We regret to say that the interim government of Nepal, displaying a cowardly grasp of what is to be required of diplomats, recalled her for speaking the truth.

Let us then return to the “Global Competitiveness Report 2013” and take a look at some rankings. Qatar is ranked 13 of 148 nations overall as to “competitiveness” while India comes in at 60 and Nepal at 117. But it is in the “labor market efficiency” rating that we get to the heart of the matter; Qatar attains a spectacular ranking of 6th among the 148 nations of the world, while India is at 99 and Nepal at 133.

We must then go behind the overall rankings and delve into the details of the performance of Qatar that so impressed the World Economic Forum (sponsor of the “World Economic Forum on India 2012” in Gurgaon, the “Indian Economic Summit 2011” in Mumbai, etc. at which events one can find such as Arun Maira, a member of India’s Planning Commission, Oommen Chandy, Chief Minister of Kerala, Prithviraj Chavan, Chief Minister of Maharashtra, Professor Bina Agarwal, O.P. Rawat, Secretary, Department of Public Enterprises, Anand Sharma, Union Minister of Commerce and Industry and Textiles, etc., etc.).

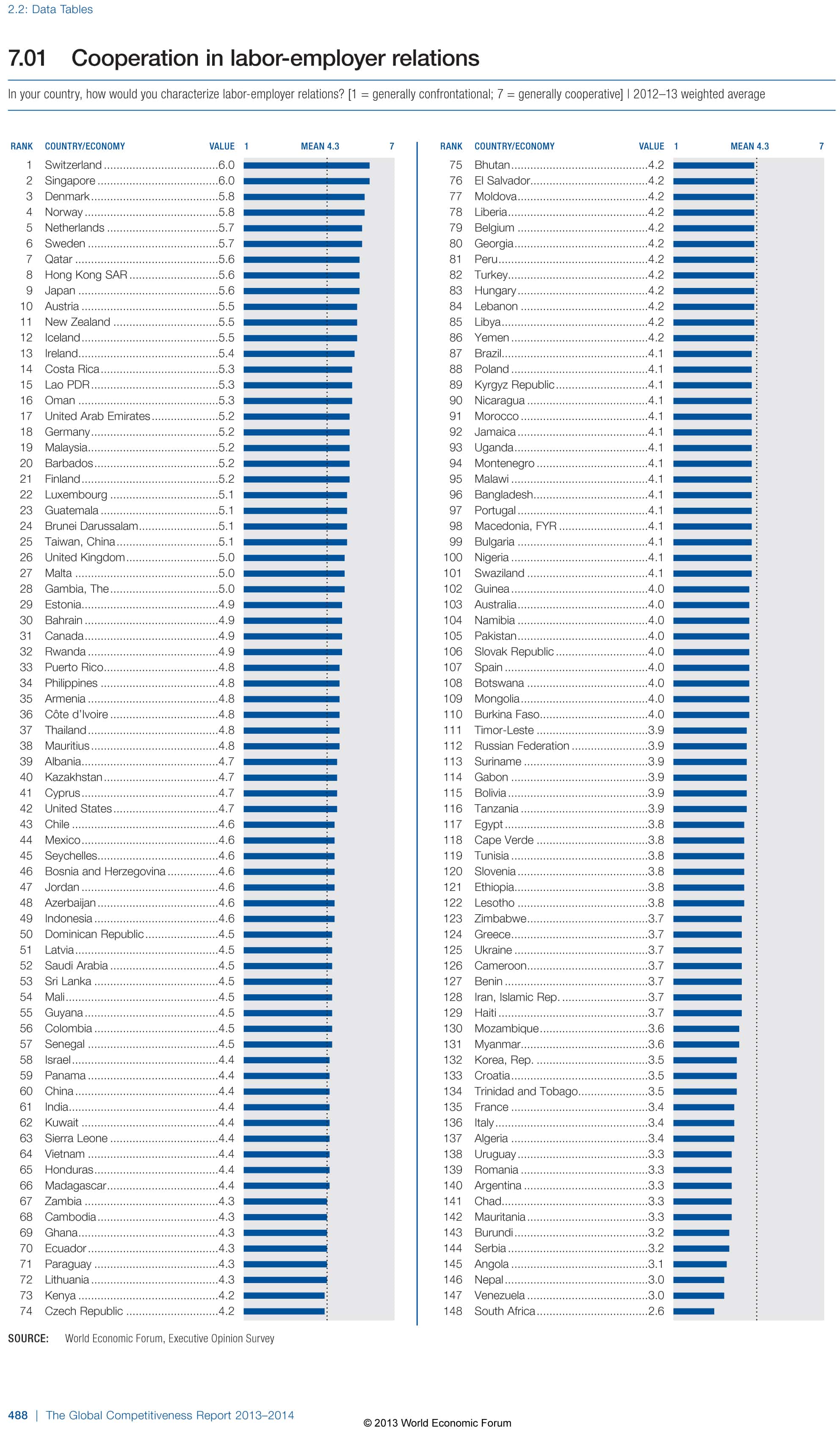

So what then, in the eyes of this so exceedingly eminent organisation, contributed to the remarkable “labor market efficiency” ratings of Qatar, sixth among all the nations of the globe? Several factors contributed to this outcome: in “Cooperation in labor-employer relations” Qatar came in 7th; in “Flexibility of wage determination” yet better in 6th; in “Pay and productivity” an outstanding 5th in the world!; and in the crucial “Hiring and firing practices” just outside the winners circle in 4th place globally.

Now we come to the essence of the matter, the secret of Qatar’s success in “labor market efficiency” in the eyes of the Masters of the Universe. In “Country capacity to retain talent” Qatar is Number One in the whole world!

When it comes to “capacity to retain talent” slavery is, beyond doubt, tops.

|

The “Global Competitiveness Report” of the World Economic Forum and its reflection in our business press is indeed “The World Turned Upside Down”. Let us then take a second look at the category “Cooperation in labor-employer relations”, and suggest that this is the key category of all categories, the key to what distinguishes decent people from those enthusiastic about enslaving children and working them to death. Let us take this category from the “Global Competitiveness Report”, turn it around and call it “class struggle”. In their ranking put right side up, with their last our first and our losers their winners, now South African labour wins the class struggle gold medal, cruising to victory with balls to spare, with Venezuela barely edging out Nepal for the silver. A great performance by the workers and peasants of Nepal, especially in comparison to Bangladesh now coming in 53rd and India far down at 88th. And taking our text from the business press, let us — in good nature — shake our heads and say to the Indian proletariat that there is a need to improve in this area.

| Print