The U.S. economy continued in a deep recession and hopes for a rapid recovery faded as new national unemployment figures of 9.5 percent were announced early this month. If one includes discouraged workers and the underemployed (those with part-time jobs who would like full-time work) in the calculations, then the figure soars to 16.5 percent. The Federal Reserve on July 15 projected an approaching jobless recovery with unemployment continuing to rise to 9.8 or even 10.1 percent this year.1 Why has the economy not recovered more rapidly as many economists, pundits, and politicians predicted it would?

The economy remains stagnant in large measure because during the last several decades the process of globalization has restructured American manufacturing industries in ways that have reduced their weight and significance in the economy and society. Investment in manufacturing in the United States has declined, while investment abroad has grown. The industrial worker core (factory workers) had been declining for some time, a result of both new technology and offshoring, and now the decline has become precipitous.2

The statistics tell the story. In 1960 out of a total non-farm workforce of 54,274,000, there were 15,687,000 manufacturing workers representing 29 percent of the total. By 2009 out of a total of 134,333,000 non-farm workers, there were only 12,640,000 manufacturing, representing just 9 percent of the total. That is, industrial workers fell in the last fifty years from almost one-third of all workers to less than 10 percent.3

Now this long-term trend has been accentuated and punctuated by an economic crisis that marks the end not only of the recent period of expansion, but perhaps the end of an era of U.S. predominance in the world market, with dramatic implications for unions and workers.

The Downturn in Manufacturing

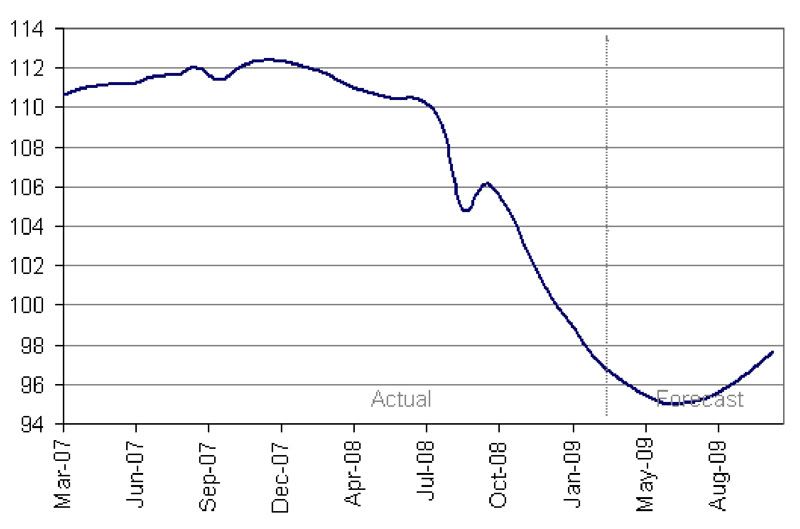

While J.P. Morgan Chase and Goldman Sachs reported profits indicating that recovery has begun for the highest of high finance, manufacturing continued to decline, even if more slowly than in the recent past. Industrial production fell by 0.4% in June, the slowest rate of decline in eight months. But capacity utilization is at an all-time record low of 68 percent. Industrial output fell by 11.6 percent in the second quarter, compared to a fall of 19.1 percent in the first quarter. Auto and auto parts production, however, fell by 32.5 percent. These continuing declines in industrial employment are responsible for the rising unemployment rate.

U.S. Industrial Production Index, Past Trend Present Value & Future Projection, Index Value. 1997=100.

Source: forecasts.org/iip.htm

Witnesses speaking before a subcommittee of the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking and Urban Affairs on July 17 testified that manufacturing would be key to recovery. Mark Zandi, Chief Economist and founder of Moody’s Economy.com, told the subcommittee that Congress must put into effect policies, such as economic incentives, that would increase investment. He noted in passing that since 2000 some five million industrial jobs had been lost.4

But, as Louis Uchitelle observed recently in a perceptive article in the New York Times, in the past economic recuperation was driven by manufacturing, at the center of which stood the auto industry. The auto industry — which includes both the Big Three and foreign-owned assembly companies employing 309,000 autoworkers, as well as the 4,000 auto parts companies employing 450,000 parts workers — had been key to economic recovery in past recessions. With the closing of many auto assembly and parts plants, the car companies are not leading that recovery, and no other industry is playing its historic role.5

The Decline of the Machine Tool Industry

Even more disturbing perhaps than the decline of the auto industry is the decline of the machine tool industry, an industry that stands at the heart of any industrial economy. The machine tool industry is made up of the machines that make machines. Every other industry depends on machine tools in order to conduct its manufacturing operations. There are about 7,000 such companies — Hardinge, Kennametal, Thermadyne, and Ingersoll are among the largest — with combined annual revenue of $25 billion. Machine tool companies produce dies, molds, cutting tools, and machining centers, some of this high-tech automated equipment, created in complexes that contain specialized foundries and machine shops. Working for these companies are engineers and high-skilled workers whose know-how represents an invaluable human capital.

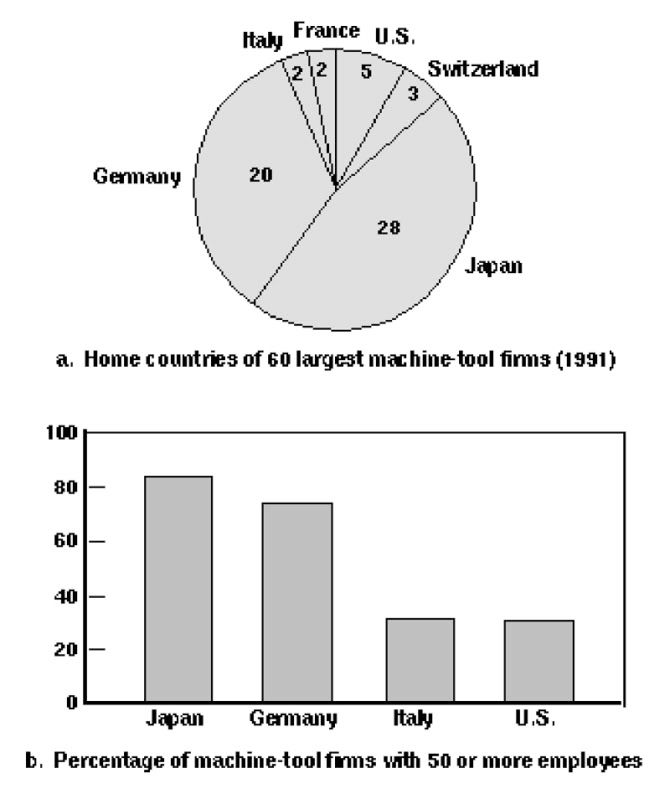

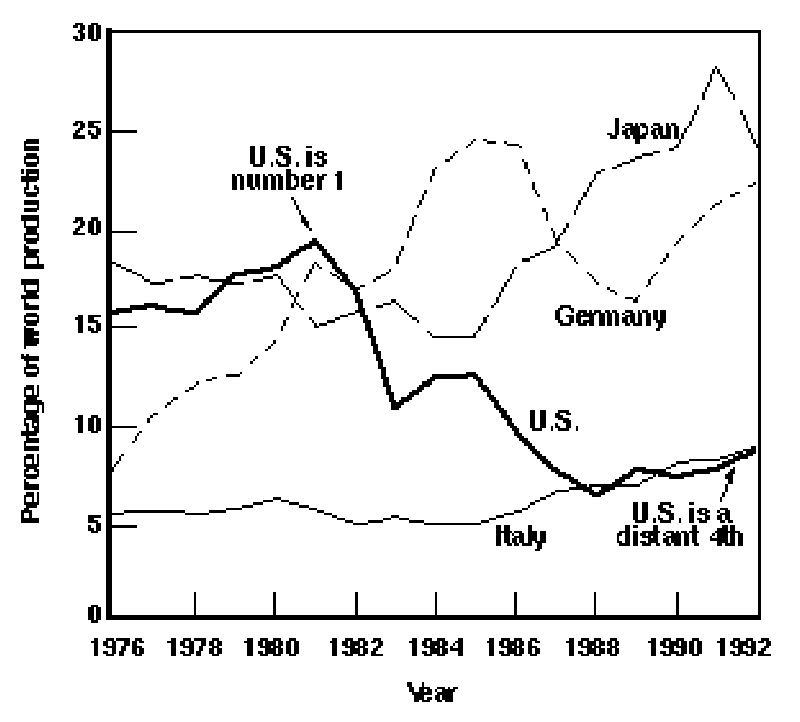

Since the early 1980s, the machine tool industry has been on the decline, a descent which has become precipitous. During the 1980s and 1990s the U.S. machine tools lost out in world competition not only to Japan and Germany.

Size of U.S. Machine-Tool Firms Compared with Those of Other Major Producers – 1993

Source: Rand Research Report, “The Decline of the U.S. Machine-Tool Industry and Prospects for Recovery,” 1993.

During the 1980s and early 1990s, the United States fell to a distant fourth in machine tool manufacture.

Decline of the U.S. Machine-Tool Industry

Source: Rand Research Report, “The Decline of the U.S. Machine-Tool Industry and Prospects for Recovery,” 1993.

During this period of increased global competition, the U.S. machine tool companies failed to keep up with developing technologies and ceded technological dominance of the field to Japan.6

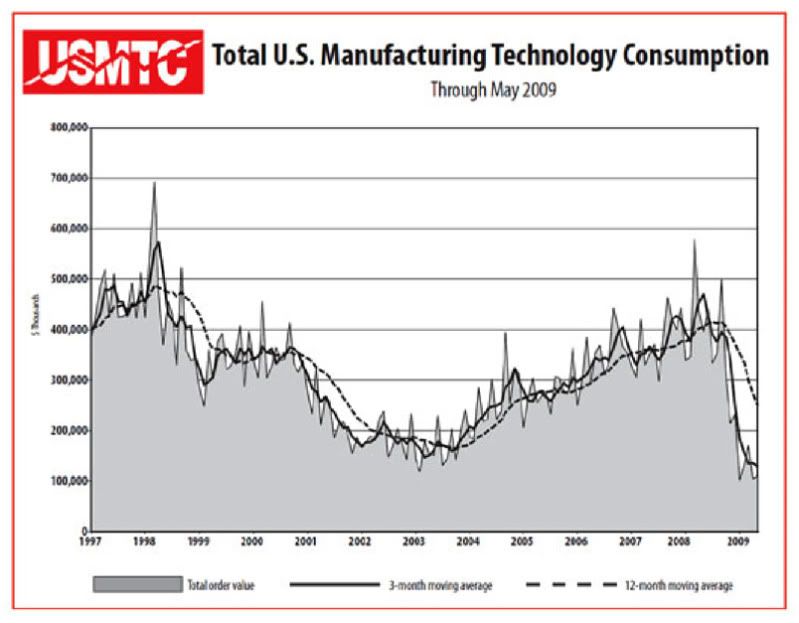

The machine tool industry’s production, sales, and profits have been uneven for some time. Today, writes one industry observer, “The U.S. machine tool industry is on the verge of oblivion.”

The Crisis of the Machine Tool Industry

Source: Gary P. Pisano and Willy C. Shih, “Restoring American Competitiveness,” Harvard Business Review, July-August 2009.

Since the crisis of the 1980s, the U.S. machine tool industry has descended to new lows, now ranked seventh in the world with an output last year of $3.8 billion.

— History —

(Thousands of U.S. Dollars)

| Year | Metal Cutting | Metal Forming | Total |

| 1996 | $4,252,641 | $565,751 | $4,818,392 |

| 1997 | $4,873,443 | $598,127 | $5,471,570 |

| 1998 | $4,578,421 | $627,329 | $5,205,750 |

| 1999 | $3,396,100 | $500,157 | $3,896,257 |

| 2000 | $3,566,064 | $458,184 | $4,024,248 |

| 2001 | $2,445,056 | $223,455 | $2,668,511 |

| 2002 | $1,926,965 | $236,865 | $2,163,830 |

| 2003 | $1,790,413 | $189,515 | $1,979,928 |

| 2004 | $2,657,861 | $185,308 | $2,843,169 |

| 2005 | $2,870,938 | $195,912 | $3,066,850 |

| 2006 | $3,761,939 | $182,443 | $3,944,382 |

| 2007 | $4,066,378 | $217,258 | $4,283,636 |

At the same time, Japan produced $15.8 billion in machine tools, Germany $15.6 billion, and China a remarkable $15 billion.7 One report says that China now produces one quarter of the world’s machine tools.8

Decline in Research and Development

The movement of manufacturing abroad, particularly through outsourcing, has had profound implications for the U.S. economy. As a recent article on “Restoring American Competitiveness” in the Harvard Business Review suggests, when U.S. corporations outsourced manufacturing, including the machine tool industry, they also ended up outsourcing research and development. Consequently, the U.S. has fallen behind in cutting edge technologies.9

The decline of the machine tool industry and the research and development which accompanied it represents an historic shift of enormous proportions. U.S. preeminence in manufacturing was based from the beginning on the machine tool industry first developed in the American armories at the very beginning of the 19th century.10 The U.S. began to overtake England in manufacturing in the mid-19th century largely because of preeminence in machine tools.11 The further development of machine tools at each stage of industrial development produced the machines that created integrated production operations, continuous processes, and later assembly line production.12 And in the mid-twentieth century it was a revolution in machine tools that ushered in automation.13 By the late twentieth century these mechanical operations were being integrated with electronics and computer controls. As this history suggests, the decline the machine tool industry signals a more general decline of the heights of industrial manufacture.

What Are the Employers and Politicians Thinking?

The American economic, political, and military elite is for its own reasons concerned about the precipitous decline in machine tools and related research and development. Military service officers, politicians, and, for example, aircraft company officials have repeatedly warned that the decline of machine tools represents not only an economic and social problem, but also, from a military point of view, a strategic problem.14 Even more worrisome to the country’s power elite should be the U.S. weakness in research and development related to manufacture.

While the United States remains the world’s dominant military power, the eclipse of manufacturing and the possible collapse of machine tools would represent a disaster of no small proportions.

What Does This Mean for the Working Class?

The decline of manufacturing generally and of the machine tool industry in particular suggests a weakening of the American industrial working class. This is not simply a question of numbers, but also of the character of the work and kind of social organizations to which it gave rise. Factory workers, because employers brought them together in large numbers and put them in charge of machines that produced commodities for the market, discovered that they had the power — through slowdowns and strikes — to affect production and therefore profits. When industrial workers struck and organized, they also became a political power, even if the unions’ conservative officials failed to turn that into an independent force.

The machine tool industry in particular assembled around itself the engineers, machinists, electricians, and other highly skilled workers who often stood at the center of their communities and of the labor unions in their plants. While often seen as the elite of the industrial world, it was tool-and-die makers and other such skilled workers who often formed the core of early organizing efforts. German and British immigrants among them brought trade-union and socialist traditions to the machine tool industry and the auto plants of the United States.

The industrial unions in manufacturing, for all their faults — and their faults were often quite serious, such as racial exclusion in the trades, an insular community consciousness, social conservatism, and political subordination to the employer and the capitalist parties — still represented a potential locus of discontent and the power to make change. Machine tool workers, whose consciousness was often a mix of craft pride and social parochialism, of union commitment and political caution, shared both the weaknesses and the potential of other industrial workers. The dramatic reduction in manufacturing and particularly of the machine tool industry will weaken these workers’ communities as well as labor unions and will undermine the potential for progressive political change in the United States.

A Political Alternative

Workers in industry and the American people as a whole have a right to demand that the government intervene to stop the destruction of entire branches of U.S. industry. What might the government do? As we have argued on other occasions with regard to the U.S. auto industry, the government could and should nationalize the auto industry, turning it over to be run by workers and consumers (who obviously could hire the technical experts they need, from accountants and lawyers to production managers and industrial hygienists).15 We have every confidence that people who have designed, engineered, and made cars for decades could now make trains, buses, and windmills.

While the unions and the public fail to act, however, investors, employers, and the government continue to permit an all-important industry such as machine tools to atrophy, and ultimately to die. What is necessary is the construction of a working class and social movement prepared to fight through direct action — demonstrations, strikes, civil disobedience, factory occupations, and so on — while at the same time creating an independent political party of working people that embodies the hopes and dreams of ordinary American people for peace, education, health care, action on the environment, and justice for all.

We do not now find any sizable contingents of workers who are willing to fight, though there have been some notable exceptions such as the Republic Window workers, the Stella D’Oro workers, and the rank-and-file Auto Worker Caravan.16 So, until working people are ready to fight, we have to continue to organize. The organizing will begin with a discussion among family members and friends at the kitchen table or with an informal get-together at the coffee shop. Those discussions will lead to the creation of small groups, a militant minority prepared to take action. The action may not come immediately, but we need to begin that discussion now.

1 Neil Inwin, “Fed Sees Heightened Joblessness Drawing Out Recovery,” The Washington Post, July 16, 2009.

2 Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Employment, Current Employment Statistics, databases, historical tables, online. I recognize that simply using the BLS categories for “manufacturing” and “private services” oversimplifies the picture somewhat, but at the same time it provides a useful baseline measure of the change.

3 Ibid.

4 “Witnesses Say Healthy Manufacturing Key to Economic recovery,” RTT News, July 17, 2009.

5 Louis Uchitelle, “Once a Key to Recovery, Detroit Adds to Pain,” New York Times, June 1, 2009.

6 Rand Research Report, “The Decline of the U.S. Machine-Tool Industry and Prospects for Recovery,” 1993.

7 Richard A. McCormack, “U.S. Machine Tool Industry Is on the Brink: How Does an Industry Survive without Any Orders?” Manufacturing & Technology News, (Vol. 16, No. 5) March 31, 2009.

8 David R. Butcher, “China’s Machine Tool Industry Coming of Age,” Industrial Market Trends (Thomas.Net), July 23, 2008.

9 Gary P. Pisano and Willy C. Shih, “Restoring American Competitiveness,” Harvard Business Review, July-August 2009.

10 Merritt Roe Smith, Harpers Ferry Armory and the New Technology: The Challenge of Change (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977), passim.

11 H.J. Habakkuk, American and British Technology in the Nineteenth Century: The Search for Labour-Saving Inventions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1967), 105-6, 168-71.

12 Alfred d. Chandler, Jr., The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1977), 240-281.

13 David F. Noble, The Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984), passim.

14 See for example, Richard McCormack, “Eroding Industrial Base Raises Concern Deep Within the Military,” Manufacturing & Technology News (Vol. 11, No. 21) Nov. 19, 2004.

15 Dan La Botz, “A Big Caravan to Washington? The Auto Crisis: Management, Labor, and the Struggle for the Future”; and Dan La Botz, “What’s To Be Done About the Auto Industry?”

16 See: www.ueunion.org/ue_republic.html; www.autoworkercaravan.org/ ; and stelladorostrike2008.com/

Dan La Botz is a Cincinnati-based teacher, writer and activist. Contact him through his home page: <DanLaBotz.wikidot.com>.