As the representatives from the European Union, the IMF, and the Greek government are trying to flesh out how Greece can use the EU’s and the IMF’s funding to remedy its fiscal position, the main question hovering above their negotiations is whether Greece can and should follow Estonia’s example in massively cutting public spending. Estonia’s public spending in 2009 was a drastic 12% less than in 2008 and this kept public deficit below 2% of GDP in 2009. Both the European Commission and the IMF have hurried to praise Estonia’s efforts; in credit markets Estonia’s credit default swaps (bets on how likely it is that Estonia defaults on its public debt) valuation has been halved since the beginning of the year (that is, the likelihood of default has halved). While it is odd that Estonia’s debt (one of the lowest in Europe, just over 6% of GDP at the end of 2009; in fact, Estonia has government reserves amounting to almost 9% of GDP) is being valued at all as it is not publicly traded to begin with, it is a sign of a general tendency to see in Estonia an example par excellence of handling the crisis. Indeed, the entire issue of public debt seems to have taken the center stage in the ensuing financial crisis on the both sides of the Atlantic — see for instance IMF’s warning.

It is true that Estonia’s numbers (public debt and expenditure, budget cuts) are sheer magic in the European context. So is the fact that these numbers have been accompanied by no street riots; moreover, the government is now probably even more popular than before the crisis. There’s justifiable cause for envy and this begs the question: should Greece, with public deficit of 13% and public debt of 113% (both as percentage of GDP), follow Estonia, bite the bullet and get down to slashing budget and wages? Similarly to Greece, Estonia has no exchange rate policy option as the Kroon is pegged to the euro. (Of course, pegs can always be un-pegged but there seems to be no political will in Estonia or in Europe to do this and by now it is also probably too late as devaluation would now make all the efforts of 2009 futile.) In other words, the question actually is whether the so-called internal devaluation works and if so then precisely how.

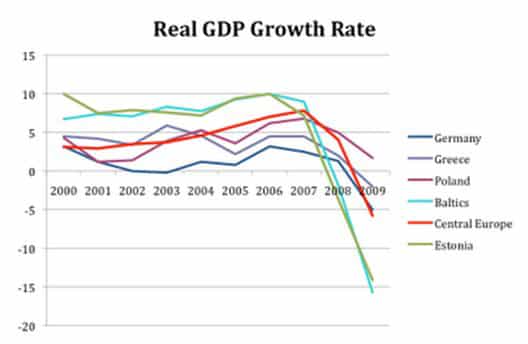

The euphoria around Estonia should die rather quickly when one looks at the GDP performance in 2009. It fell nearly 15%; Greece’s GDP contracted just 2%. The figure below shows real GDP growth rates in Estonia, the Baltics taken together (for comparison), and Central Europe (Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovak Republic and Slovenia; simple averages; all data from Eurostat).

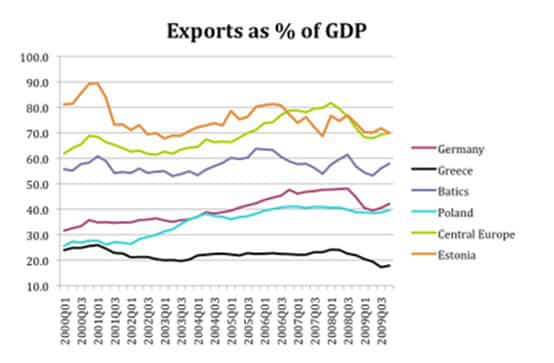

The GDP data show one intriguing figure that really begs the question: how come Poland is still growing? Well, not only is Poland growing, its exports haven’t really slowed down at all during the crisis, as is evident from the next figure below.

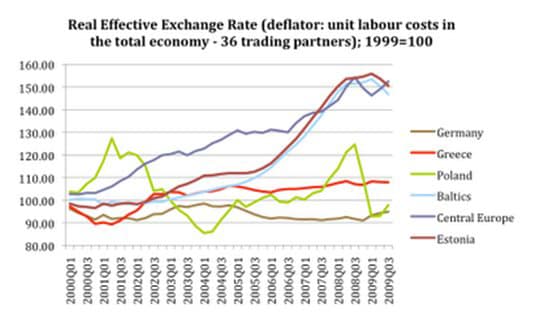

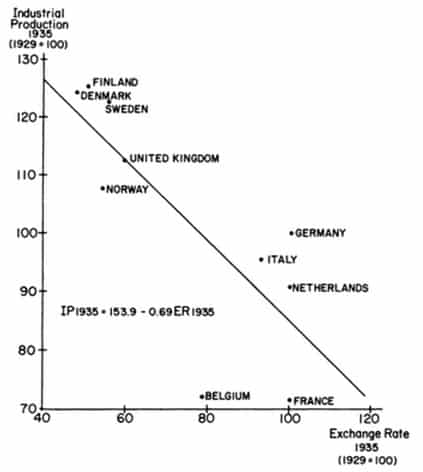

A look at the real effective exchange rates clarifies the story with a rather amazing picture: Poland’s floating currency seems to have done what it’s supposed to do in the crisis like that — devalue. This has considerably softened the crisis, and, contrary to the Baltic and other Central European economies, Poland has very quickly regained its export competitiveness. It is clear that at least partially this was deliberate policy as is explained by the Polish Central Bank president in a Financial Times piece published posthumously last week. It remains to be seen whether Poland remains on this course of sanity.

That devaluation works in situations like what we are currently experiencing shouldn’t really come as that much of a surprise. There’s an interesting parallel from the Great Depression and its aftermath, depicted in the figure below (the figure comes from Barry Eichengreen and Jeffrey Sachs, “Exchange Rates and Economic Recovery in the 1930s,” Journal of Economic History, 45. 4, Dec., 1985, 925-946: p. 936).

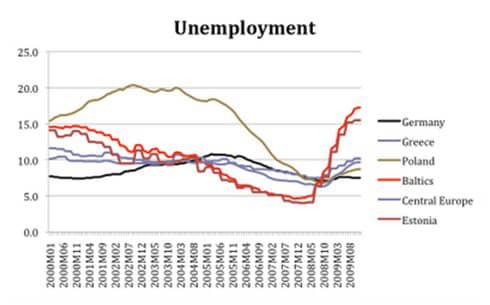

So, what is the price paid by Estonia and the other Baltic states? Again, one would expect that, with the heavily overvalued currencies, the main suffering would take place in the labor market and this is indeed what is happening in the Baltics. While the Baltic media is fanfaring that the unemployment figures didn’t rise last week for the first time since the crisis started, it seems clear that under conditions of weak domestic demand (engendered through anemic borrowing and uncertainty amid wage cuts) and lagging productivity growth (especially if compared to Germany and Scandinavia — Baltic and Central European export industries are largely part of German or Scandinavian production networks) there’s no quick end to the crisis in sight.

While the respective national statistical offices report some price deflation and falling real wages in the Baltic economies, the former are merely cosmetic and the latter in fact contribute to collapsing domestic demand. It has led to positive external balance over the last quarters, but this is not due to exports, but rather because of the breakdown of the capacity to import. Without actual devaluation, in other words, such internal devaluation is bound to last for years in the Baltics and to a lesser extent in the Central European economies generally (other than in Poland, of course). Growth is bound to stay anemic and, because of lagging productivity, exports simply cannot pick up fast and strongly enough to offset the weak domestic demand. Polish companies at the same time could take advantage of their relatively higher export competiveness.

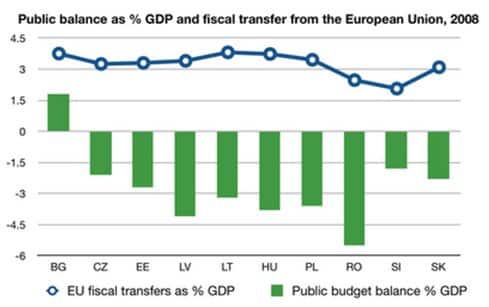

However, without European fiscal transfers, most Baltic and Central European economies would have similar levels of public deficits as Greece, and, accordingly, rising levels of debts. See figure below. (Fiscal transfers from the European Union are annual transfers through the so-called structural funds. Here, the EU fiscal transfers include funds from three main sources: Cohesion, Rural Development, and Fisheries Fund; calculations by the author.) Continued high unemployment will lead, especially in the Baltics, to increasing public debt — or to even more unemployment until the situation becomes untenable for some who then emigrate.

Thus, one can draw the following conclusions: first, in essence, Estonia and the Baltic economies are simply mirror images of Greece and other PIIGS. In the former, the private sector carries the cost of the crisis, in the latter mostly the public sector (social safety nets); because of the in-built inflexibilities, both are cases of free riding: the former export public deficits, the latter unemployment to the rest of Europe. Second, Central European economies, except Poland, seem to follow Germany (weak domestic demand, high levels of exports) through high levels of integration into the latter’s production networks and tailwind Germany’s export machine. This assumes recovery in Europe and the world. The danger is that these economies must match Germany’s productivity growth or else their effective exchange rates start to appreciate again. This is precisely the trap the PIIGS fell into. And third, Poland, with its floating currency and relatively large domestic market, seems to be faring the best so far among Eastern European economies. Such divergence within Central and Eastern Europe will probably become only more pronounced in the coming years.

It is important to understand that these woes have a common cause: unifying rather unequal countries into an economic union. That this is bound to create problems for PIIGS was brilliantly predicted by Jan Kregel already in 1999. Simply put, the eurozone assumed and still tacitly assumes either growing German wages or growing productivity in the rest of Europe. Neither has been the case.

The Baltic economies with pegs, and with its insistence on keeping the pegs, have simply tied the noose around their own necks, trading monetary stability for, first, high financial fragility, and second, very probably long-term high unemployment and debt deflation in the private sector. This will probably result in waves of emigration, growing social problems, and the like. In other words, the costs have been shifted to the future, and they are more than likely to equal Greek troubles in fiscal terms. Estonia is Greece in disguise. It remains to be hoped that the EU and the IMF recognize that and refrain from simplistic fiscal retrenchment that makes problems only worse as the Greek domestic demand and, accordingly, government fiscal position will only weaken further. This results, as we have seen in Estonia, in real economic depression, which is GDP contraction in double digits.

Rainer Kattel is Professor and Chair of Public Administration and European Studies, Tallinn Technical University. The article was originally published in the faculty blog of the Department of Public Administration, Tallinn University, and republished by International Development Economics Associates on 21 April 2010; it is reproduced here for non-profit educational purposes.

|

| Print