Jesse Freeston: Last week, the Bolivian city of Cochabamba and the country’s president Evo Morales played host to the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth. The conference sought to distinguish itself from the United Nations conferences for giving a greater voice to civil society and expanding the conversation beyond just greenhouse gas production. The Real News spoke to Jean Friedman-Rudovsky, a Bolivia-based freelance journalist, who recently returned from the conference.

Jean Friedman-Rudovsky: At the official conference there were 35,000 participants, 142 countries represented, and 47 of those countries sent official delegations.

Evo Morales: We are here today because the so-called developed countries didn’t fulfill their obligation to commit to substantial reductions in greenhouse gases in Copenhagen. If these countries had respected the Kyoto Protocol, and had agreed to substantially reduce their emissions inside their own borders, this conference wouldn’t have been necessary.

Jean Friedman-Rudovsky: There were so many proposals and ideas that are sort of popping up all over the place — everything from the International Criminal Court on Climate Change to a global referendum to pushing this idea of climate reparations and climate debt. I think the message the summit sent was if you guys aren’t going to be able to do this, then we need to take matters into our own hands. People from all over the global South are gonna get together and talk about their experiences, talk about solutions, and try to push that message to be incorporated into the next summit of world leaders.

Evo Morales: If in the end they don’t listen, how will we organize and empower ourselves in society, in the workplace, all over the world to force the developed countries to respect the conclusions of the world’s social movements?

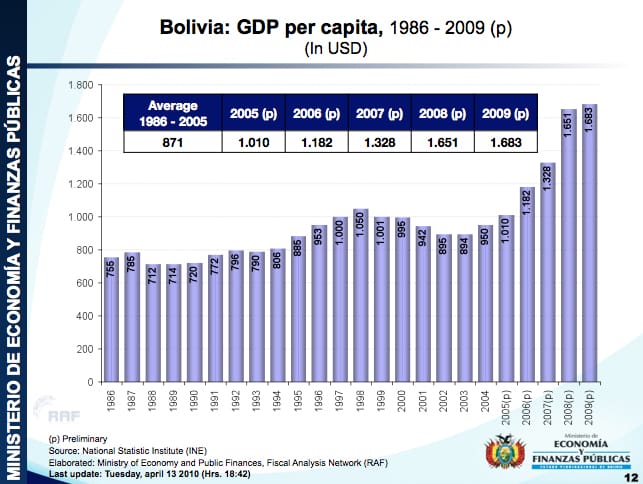

Jesse Freeston: As the summit wrapped up in Cochabamba, Bolivia’s finance minister Luis Arce was in Washington, D.C., giving a presentation of Bolivia’s economic alternative to neoliberalism and its results in the four yeas since Morales took power.

Luis Arce: The GDP per capita: when we formed the government in 2005, it was US$1,010 per Bolivian; now we have US$1,683 — a growth rate of more than 60% in four years. We have now the highest growth rate in the region, from Alaska to Argentina.

Jean Friedman-Rudovsky: Over the past year and a half, you have had a global economic recession, and the fact is, in Bolivia, things have not gotten worse over the past year, which is really saying something. It’s South America’s poorest nation, but, as you know, the economy is growing.

Jesse Freeston: As for how such success was arrived at, Arce primarily credited the nationalization of the oil and gas industry for increasing government revenues, revenues which are then directed towards infrastructure, key industries, and social programs.

Luis Arce: We have resources. We have hydrocarbon, mining, electricity, and environmental resources that we can use to create a new Bolivia. Bolivia will invest in industry, manufacturing, tourism . . . and so on. So, who can do this job for us? Of course, the private sector cannot do that, because the private sector is seeking another thing — profits and so on. The only actor that could do it is, of course, the state.

Jesse Freeston: Some are suggesting that Bolivia’s extraction economy is creating a contradiction.

Jean Friedman-Rudovsky: Evo Morales is leading this world movement to protect the rights of Mother Earth. Yet, in his own country, there is this extractive industry that is the base. The problem is you can’t just cut off all the extractive industries right now: the economy would crash, people would starve, people would die.

Jesse Freeston: The Real News asked the minister about this apparent contradiction.

Luis Arce: The current law, you know, has parameters for mining and hydrocarbon exploitation, so we don’t have problems with that. We have already taken care of natural resources and the environment. No problem. There’s no contradiction at all.

Jesse Freeston: But, even during the conference in Cochabamba, a series of direct actions were taken by community groups around San Cristóbal’s silver and zinc mine in the neighboring department of Potosí. They claim that their water supply is being depleted by the mine, which is run by the Japan-based Sumitomo Corporation.

San Cristóbal Activist: We demand that the company preserve the environment, not contaminate it.

Jesse Freeston: They want the company to pay for the six hundred liters of water per second that it uses, which it currently gets for free under an agreement with the government that preceded Morales’. Actions taken by protesters included blocking all railroad and road shipments for almost two weeks and burning down a company office building. The protesters want their water resources replenished as well as funding for electrical infrastructure projects. The blockade has since been lifted, but the group pledged to take action again if they see no progress in the next month. At the UN Climate Summit in Copenhagen in December, Danish authorities chose to repress street protests, where almost 1,000 people were arrested, most of which after being penned in for hours by police. In contrast, the Morales government did not attack or arrest the protesters in Potosí. Nonetheless, the actions did bring Bolivia’s resource dilemma to the forefront. In an interview with Democracy Now!, President Morales acknowledged it as a challenge.

Evo Morales: We need in-depth studies on this. If we want to defend Mother Earth and the rights of Mother Earth, any project for industrializing natural resources has to respect the regeneration of bio-capabilities.

Jesse Freeston: But he had harsh words for organizations that chastise the government for supporting extraction and infrastructure projects.

Evo Morales: Those foundations, NGOs, said, “Amazon, no oil.” So they’re telling me that I should shut down oil wells and gas wells. So, what is Bolivia going to live off of? Let’s be realistic. . . . They tell me, “Don’t build roads.” And another one says, “Don’t build dams.” The day before yesterday, when I was just back here, I announced that we’re going to build a road from Oruro to a place near here. That is the most widely applauded project by the grassroots people, because the people need to be able to have access. If we just look out here, in El Alto, every day they’re asking for small-scale dams. So, when NGOs and some leaders say “No,” they’re not interpreting the needs of their grassroots. That is the truth.

Jesse Freeston: Bolivia’s central proposal for overcoming reliance on extraction is the idea of climate debt. At the Copenhagen Summit in December, Bolivian climate negotiator and ambassador to Switzerland Angelica Navarro explained the concept of climate debt.

Angelica Navarro: . . . Therefore Bolivia considers that it’s the developed countries that owe climate debt to developing countries. This debt has to be paid to us. . . . This debt has to be twofold. The first one is that they have to repay, regarding all their emissions. . . . They have to free space for developing countries to carry on sustainable development, because we don’t want to develop in the irresponsible way they have done.

Jean Friedman-Rudovsky: Making the industrialized world responsible for helping and aiding countries in the developing world to not just continue resource extraction but to really jump to clean energy. So, they’re really trying to push that idea to get financial and technical resources to be able to move on a cleaner path themselves.

Jesse Freeston: This tension that comes with extraction-based development isn’t exclusive to Bolivia. Ecuador recently became the only country in the world to include the rights of nature in its Constitution, but, like Bolivia, the Ecuadorean government also funds its social programs with extraction revenue. President Rafael Correa has suggested another way that developing countries with resources could overcome this problem.

Rafael Correa: Perhaps the audience isn’t aware of the Yasuní ITT initiative. At more than 900 million barrels of oil, it’s the largest reserve in Ecuador. But it’s in a very ecologically sensitive area: Yasuní National Park. We’ve proposed to the world that we leave this oil underground, thereby avoiding the emission of more than 400 million tons of CO2, whose market value would be around 5 billion dollars in carbon credits. We’re asking for 3.5 billion dollars — half the expected profits from the reserve. The one making the most sacrifice here is Ecuador. Financially, our interest lies in extracting the oil. We want to work together to avoid the acceleration of climate change at least — a climate change that was not caused by the poor countries but by the rich countries. So, we are demanding co-responsibility with the rest of the world. If this doesn’t happen, we will have to extract the oil.

Jesse Freeston: Industrialized governments have yet to show consideration to these kinds of ideas. In fact, the Obama administration has cut some aid to Bolivia and Ecuador following their rejection of the Copenhagen Accord. US climate negotiator Todd Stern told the Washington Post that “the U.S. is going to use its funds to go to the countries that have indicated an interest to be part of the [Copenhagen] Accord.” In the meantime, Minister Arce confirmed that Bolivia has plans to expand its extractive industries in order to finance its many goals, such as food self-sufficiency and extreme-poverty eradication.

This video was released by The Real News on 26 April 2010. The text above is an edited partial transcript of the video.

|

| Print