Three death-sentenced men went on hunger strike in Ohio State Penitentiary on January 3 to win the same rights as others on death row in the state. On Saturday January 15, the twelfth day of their protest, a crowd of supporters gathered in the parking lot by the tiny evangelical church at the entrance to the prison on the outskirts of Youngstown. They ranged from the elderly and religious to human rights supporters to members of various left groups. They were expecting to participate in the first of a series of events in coming weeks to support the men on their road to force-feeding, or even possible death. Things did not turn out as expected. For once, this was for the better.

The day’s events began when a small delegation made up of the hunger strikers’ relatives and friends (Keith Lamar’s Uncle Dwight, Siddique Hasan’s friend Brother Abdul, and Alice Lynd for Jason Robb), went up to the prison through the snow and ice to deliver an Open Letter addressed to OSP Warden David Bobby and Ohio’s state prison officials. The letter, which supported the demands of the hunger strikers, was signed by more than 1,200 people including the famous (Noam Chomsky), human-rights-leaning legal experts from Ohio and around the world, prominent academics and writers, and ordinary retired teachers and religious ministers. It was Saturday, so Warden Bobby was not there to meet the delegation, but he’d been aware of their coming and left someone at the front desk to take the letter.

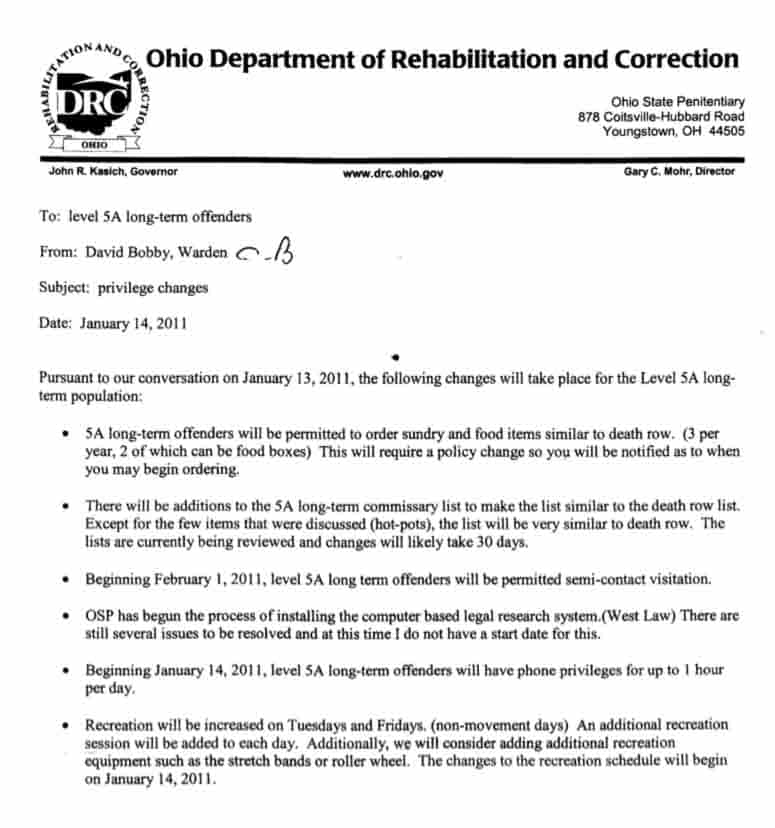

Hopeful word of a settlement of the hunger strike had been circulating among a few friends and activists for two days. It was definitively confirmed that morning when visitors to Jason Robb received a copy of a written agreement from Warden Bobby (see below) outlining a settlement that provided practically all of their demands, despite his insistence at the beginning of the strike that he would not give in to duress.

Although the hunger strikers told me that they were optimistic from the very beginning, there were grounds to expect a harder battle. Bomani Shakur (Keith Lamar) described an incident with the Deputy Warden at the beginning of his protest.

“You know, LaMar, a human being can only go so long without food,” he chided Shakur.

“Yeah, I know,” replied Bomani, “but according to the state of Ohio I’m not human, so I don’t have to worry about that!”

Nonetheless, Warden Bobby and his deputies had been meeting with the hunger strikers for some days and they agreed that they would end their protest upon receipt of the warden’s letter. Friends and relatives who came to visit Siddique Hasan and Keith Lamar (aka Bomani Shakur) told visiting friends and relatives similar details about the end of the strike. Both men said that they had resumed eating.

Shakur told one of his friends that he’d “just been eating hot-dogs.” She replied that it was crazy to eat such things on an empty stomach. Bomani just laughed and said, “but I was hungry, man!”

The delegation returned to the crowd and began the rally. The surprise was revealed to all. The hunger strike was over.

Jason Robb’s victory statement was relayed to the crowd. He wanted to thank everybody for their support, for without it the men would have won nothing. But now, he said, it was time to shift the focus to the fact that five men, including the three hunger strikers, are awaiting execution for things they did not do.

“The energy around our protest went viral,” he told Alice and Staughton Lynd on a prison visit. “This time around the fight was for better prison conditions. Now we begin fighting for our lives.”

Why a Hunger Strike?

The “Lucasville Five” includes the three hunger strikers plus Namir Mateen, who did not join the hunger strike due to medical complications, and George Skatzes, who was transferred out of isolation at OSP after he was diagnosed with chronic depression. All five are awaiting execution for a variety of charges, mostly complicity in the murders of prisoners and a guard during the Lucasville prison uprising of 1993. In a case that resembles that of the Angola 3 in Louisiana, they have been held in solitary isolation for 23 hours a day for more than 17 years, since the evening the uprising ended. This is despite the fact that three of them helped negotiate a settlement of the uprising that undoubtedly saved lives, and despite a promise within the agreement that there would be no retribution against any of the prisoners.

The Ohio prison authorities went back on their word. They not only put the five men in isolation but they built the supermax prison at Youngstown to hold them that way in perpetuity. Having built the prison, they had to fill 500 beds, despite the fact that a small Secure Housing Unit at Lucasville had never been full. But the 1990s were the decade of the supermax. So men who were charged with minor offences found themselves locked up in Youngstown on “Level 5 security,” meaning that they were held for 23 hours a day in a cell no bigger than a city parking space. The steel-doored cells and even the recreation areas where they spent an hour a day were built in such a way as to ensure that they would never have contact with another living being — human, animal, or plant. “Outdoor recreation” was in a cement-walled enclosure that was only outdoor if you consider that the roof is a steel grille. Hundreds of men have come and gone since 1998. Only four, the three hunger strikers and Namir Mateen, remain locked up in perpetual isolation.

A case is underway in the Middle District Court of Louisiana that is likely to judge this kind of treatment as a violation of the eighth amendment prohibitions on cruel and unusual punishment. It may be that the Ohio authorities see the handwriting on the wall and they want to improve the conditions of Ohio’s supermax before they are forced to do so by another court ruling, like the Wilkinson vs Austin case of 2005 in which the US Supreme Court forced them to improve conditions in the supermax.

One of the holdings of the Supreme Court instructed the Ohio authorities to follow Fifth Amendment provision on due process. In 2000, two years after the supermax opened, they began giving annual reviews to the death-sentenced Lucasville prisoners. But the reviews are not meaningful. One of the reviews even concluded, “You were admitted to OSP in May of 1998. We are of the opinion that your placement offense is so severe that you should remain at the OSP permanently or for many years regardless of your behavior while confined at the OSP.” Thus, the four have been condemned to de facto permanent isolation.

This lack of meaningful review, as well as the continued lack of human contact despite the agreement that ended the Youngstown hunger strike, might yet be the focus of litigation not just in Ohio but in other supermaxes around the United States, such as California’s notorious “Secure Housing Unit” at Pelican Bay State Prison.

The conditions of supermax are a running sore on the US human rights record, a sort of elephant in the room that few people want to talk about. Yet there is a growing sentiment among experts and policymakers against extreme isolation, both because of its cost but also due to the judgment that it is a form of torture.

And it is these conditions of extreme isolation, without hope of ever touching a fellow human apart from a prison guard, that drove these men to the ultimate protest of hunger strike. As Bomani Shakur wrote in a statement that announced his hunger strike, none of the men wanted to die. But in such conditions of isolation, and in the absence of any way of proving to the authorities that they were not a security risk if allowed to mix with other prisoners or have semi-contact visits, depriving themselves of food was the only non-violent means of protest that remained for them.

What Now?

For the Lucasville Five, the main attention turns now to their wrongful convictions and to the death penalty itself. Ohio is the only state in the US that executed more men in 2010 than in 2009. And it is second only to Texas in its rate of executions. For the past two years, the state has attempted to execute one man a month, although that attempt has been slowed by botched executions and by some surprising grants of clemency by former governor Ted Strickland. One can only hope that moves away from the use of the death penalty in states like New Mexico and, most recently, Illinois are the beginning of a more general move to do away with this backward policy.

The hunger strikers expressed their hopes, to relatives and other visitors, that the energy that built up around supporting their recent protest could now be turned toward getting them off their death sentences and allowing them to prove their innocence. Ironically, the improved conditions that they won through hunger strike could help in this regard. Among their demands — increased time outside of their cells, semi-contact visits, and equal access to commissary — was the demand that they be allowed to access legal databases like other death-sentenced prisoners, so that they could work toward their appeals.

For now, this is most important to Bomani Shakur. In a shocking recent decision, a district court judge affirmed the recommendation of the magistrate against his petition for habeas corpus without any discussion of the merits of the judgment. Shakur believes that the judge made this seemingly rash judgment in retaliation for his role in the hunger strike. Whether he has reason to believe this or not, he and his counsel now have to turn to the Federal Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit. In real terms, what might have been a further process of five years to execution now seems to have been shortened to perhaps three. The US judicial system is strongly biased against appeal, even in most egregious cases of injustice. So the Lucasville Five now have a hard case to argue. It is a case where public opinion and social movement may have more impact than the law, just as public pressure seems to have played a decisive role in winning a successful end to the hunger strike after such a short period.

Bomani Shakur told Alice and Staughton Lynd that the denial of his habeas petition by the district court makes him more determined and focused on what he needs to do in the next few years. Activists and supporters in Ohio and beyond will be asked to find the same kind of focus.

The Agreement That Ended the Hunger Strike

Denis O’Hearn, Director of Graduate Studies, Sociology Department, Binghamton University – SUNY.

var idcomments_acct = ‘c90a61ed51fd7b64001f1361a7a71191’;

var idcomments_post_id;

var idcomments_post_url;