The unemployment rate edged down to 8.9 percent in February, as the Labor Department reported that the economy generated 192,000 new jobs. This number is undoubtedly inflated some by the weather-weakened January performance, when the economy generated just 63,000 jobs. The unemployment rate has now dropped by 0.9 percentage points in the last three months. During this period job growth as reported by the establishment survey has averaged just 136,000, only slightly faster than the 90,000 rate needed to keep pace with the growth of the labor force.

It is difficult to reconcile the sharp drop in unemployment with the weak job growth. Generally, the establishment survey is much more accurate since it has a far larger sample and it is benchmarked every year to unemployment insurance data, which provide a near census of payroll employment.

Other data in the establishment survey are consistent with the picture of modest job growth. Average weekly hours were flat at 34.2 for the month. This is up from the trough of 33.7 in June of 2009, but no higher than the level hit in May of last year. The growth in average hourly wages continues to slow slightly, falling to just a 1.6 percent annual rate over the last quarter compared with a 1.7 percent rate over the last year. These data certainly present no evidence of a marked uptick in the demand for labor.

Most of the job growth is concentrated in health care, employment services, and durable goods manufacturing. These three sectors averaged 24,000, 28,000, and 35,000 new jobs per month, respectively, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the job growth since November. While the employment services sector is often viewed as a harbinger of future job growth, it is worth noting that this sector added 34,000 jobs per month in the same months last year.

Other sectors are notable for their weakness. Retail trade added just 6,000 jobs on average for the last three months, while restaurant employment rose by an average of less than 9,000. On the plus side, construction has added an average of 2,000 jobs per month, suggesting that employment in the sector has reached bottom. State and local governments shed an average of 21,000 jobs. This rate of job loss is likely to accelerate and will be a serious drag on an already weak labor market.

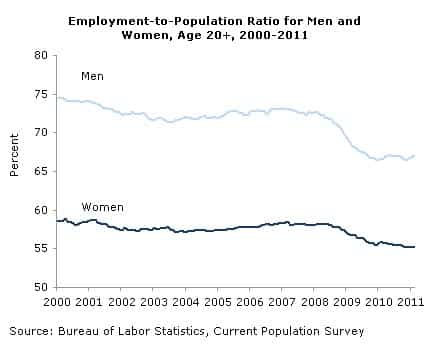

On the other side the household survey shows clear evidence of an improving labor market, at least for men. The unemployment rate for men over age 20 fell from 10.0 percent in February of last year to 8.7 percent last month. The employment-to-population (EPOP) ratio has risen by 0.4 percentage points over this period. By contrast, the unemployment rate for women over age 20 stayed constant at 8.0 percent over the last year. Their EPOP actually fell by 0.6 percentage points over this period. The EPOP for men is still down by 6.1 percentage points from its pre-recession peak and 7.4 percentage points from its peak in 2000. For women, the February EPOP is 3.3 percentage points below the pre-recession peak and 3.6 percentage points below the 2000 peak.

Black men have shared more or less equally in these gains with a 1.6 percentage-point drop in their unemployment rate to 16.2 percent and a 0.2 percentage-point increase in their EPOP over the last year. By contrast, the unemployment rate for black women has risen by 0.9 percentage points while their EPOP has fallen by 0.7 percentage points.

Other data in the household survey also show evidence of an improving labor market. The number of people employed involuntarily part-time is down by more than 800,000 from the levels of last summer. The number of discouraged workers is down from the year-ago level for the second consecutive month. Perhaps most striking is a sharp drop in the number of workers who have been unemployed less than five weeks. The level reported in February is the lowest since September of 2007 and in fact is lower than any level reported in the 90s.

However, there is nothing to suggest the strong job growth necessary to restore full employment. At the rate of job growth over the last three months, it would take almost 14 years to get back to normal rates of unemployment.

Dean Baker is an economist and Co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, in Washington, D.C. This article was first published by CEPR on 4 March 2011 under a Creative Commons license.

| Print