Guy Hocquenghem. The Screwball Asses. Trans. Noura Wedell. Semiotext(e), 2010. 88 pp. $12.95

“Speak to my ass. My head is sick.”

— Southern French proverb

|

This little book was first published as an anonymous essay at the end of Félix Guattari’s Recherches no. 12, its March 1973 special issue titled Trois Milliards de Pervers [Three Billion Perverts]: Grande Encyclopédie des Homosexualités. The issue was seized and destroyed by the police and banned by de Gaulle. Guattari was fined 600 francs. A year later, while on a visit to Paris, my friend Daniel Guérin wrote a note to a bookseller on Montparnasse requesting that he sell me a copy. The book was a kind of scrapbook of radical gay theorizing, cartoons, erotic drawings and photos — a glorified zine before zines — loosely organized by topics like “Arabs and Gays” (pédés), “Masturbation,” “Cruising,” “Pedophilia,” “Sazo-Mado”. . . .

A steady stream of friends and petitioners seeking assistance for one cause or another passed through Guérin’s apartment. I first met Guy there. Guy was a Soixante-huitard (May ’68er) and one of the founders of the Front Homosexuel d’Action Révolutionnaire (FHAR), formed in 1971 by gay men and lesbians from the Mouvement de Libération des Femmes (the lesbians soon left the FHAR). The FHAR meetings that Guérin took me to — at the École des Beaux-Arts and, one evening outdoors in the dark at the Bois de Vincennes — were chaotic and exuberant the way radical gay groups in the United States at the time were, and that is reflected in the pastiche quality of the banned book.

Guy’s book Le désir homosexuel had just been published in 1972, and The Screwball Asses addresses some of the same issues, but its style is closer to a récit or narration than a book: personalistic, free-flowing; twelve short, untitled but numbered chapters, each introduced with an epigraph like the one at the beginning of this review. Guy’s text is a provocative, pithy, kaleidoscopic, aphoristic critique — and self-critique — of the ways homosexual desire is deformed by phallocratic capitalism and a leftist practice that reproduces heterosexist and bourgeois mores. It critiques the delusions of the newly emergent gay liberation movement and might even be viewed as a predictor of the neoliberal identity politics of assimilation and “homonormativity” embraced by most of the gay movement three decades later. His critique is filtered through Lacanian, Freudian, Deleuzian, and Saussurean lenses that are more developed in Homosexual Desire and succinctly explained by Jeffrey Weeks in his preface to the English translation (1978):

. . . the aim is to find unalienated forms of radical social action, and these cannot be traditional centralized structures (especially of the working class), because these, too, are complicit with capitalism. The model of alternative modes was provided by the spontaneous forms of activity developed in France in 1968, “fusions of desire” which escape the imprisoning force of the “normal”. Schizoanalysis provides the alternative: the schizophrenic is not revolutionary, but the schizophrenic process is the potential of revolution, and only in the activity of autonomous, spontaneous groupings, outside the social order, can revolution be achieved. The result, which is central to Hocquenghem’s project, is a worship of the excluded and marginal as the real material of social transformation.1

In dissecting the homosexual’s location in a capitalist society that reproduces its norms of consumption and fetishization, as well as alienation, even in sexual rebels, thereby fracturing a polymorphous or nondifferentiated sexual desire, Guy’s text anticipates the extreme forms of role playing and marketing that emerged a few years later with the clone and its myriad colored hankies and accoutrements:

Yes, we copy normal relations, we either occupy the place of the subject or that of the object, but we copy them in any case. Today’s homosexual does not embody polymorphic desire: he moves univocally beneath an equivocal mask. His sexual objects have already been chosen by social or political machination, and they are always the same: either weaker or stronger, older or younger, more in love with him or he more in love with them, more bourgeois or more proletarian, primitive or intellectualized, uber-male or sub-male, black or white, Arab or Viking, top or bottom, and so forth. Politics has already done its underground work. If, to boot, consciousness gets involved in political struggle, then the heterosexual and exogamic tendencies of today’s homosexuality will become a caricature, and we will see more and more cases where a dick can only make love to a head and a head to a dick. (17)

In present-day unfree society, homosexuality (like heterosexuality) is channeled, controlled by the dominant capitalist-heterosexist mode. If this was true in 1973, it is even more true today, when the gay agenda is less a challenge to the dominant society than a plea for acceptance into it, when it is marketed with the alphabet soup “LGBT” brand, when minority forms of homosexuality have been marginalized (SM) or anathematized (pederasty and pedophilia) and accommodating forms promoted (religion, marriage), when militarism and patriotism masquerade as liberation and homonormativity reigns. Even as it struggles to free itself, homosexuality remains trapped:

More often than not, we homosexuals are not abnormal; rather, we have failed normalcy. We are as codified by the bourgeoisie as the latter has sexually codified workers by making them failed bourgeois. Rather than being lovers in order to breathe, we are queer [pédés] in order to escape asphyxia. Rather than pretending to be virtuous, we pretend to be dissolute. And if the self-management of desire turned out to be virtue, we would refuse it, already intimating discipline and obligation there. As long as we are not burned at the stake or locked up in asylums, we continue to flounder in the ghettoes of nightclubs, public restrooms and sidelong glances, as if that misery had become the habit of our happiness. And so, with the help of the state, do we build our own prison. (25)

The book does not see the Left as offering a positive alternative, even though the gay movement was strongly influenced by it, as it was by the women’s movement — the former more so in France than in the United States. On the contrary, the FHAR reproduced “the cruel internal aggressiveness that we had picked up in the trashcans of Leftism”:

Like the women’s liberation movement that inspired it, the revolutionary homosexual platform emerged with Leftism and traumatized it to the point of contributing to its debacle. But while they fissured Leftism by revealing its phallocentric morphology and its censure of marginal sexualities (and of sexuality in general), these autonomous movements, despite their refusal of hierarchy, continued and continue to replicate the conditioned reflexes of the political sector that produced them: logomachy, the replacement of desire by the mythology of struggle, the use of charm diverted to public discourse and considered to be a nuptial parade and an accession to power. (26)

His criticism of the Left focuses on mind-set, language, sectarianism, and style:

Not only have Leftists blocked off their senses, they have also constructed a language in which half the words are suspect, or tainted because they have been colonized, swindled of their meaning either by religion, by the bourgeoisie, or by Marxist or Freudian ideologies. . . . If you’ve got nerve, try pronouncing the words fraternity or benevolence in front of a Leftist assembly. Must we deduce from this impossibility that such things are not even remotely possible? Well, Leftists seem to have decided upon it. They have given themselves over to the studious exercise of animosity; they are engaged in deriding everything and anyone, regardless of whether they are present or absent, friend or foe. Theirs is not a system for progressing through contradiction, or for passing from one contradiction to another, but for wallowing in it. What is at issue is not to understand the other but to keep watch over him and be ready to smack his fingers if ever he reaches out. (31-32)

Already in 1973, he sees in the FHAR a failure of gay liberation to merge activism and desire, to overcome its “phallic surcharge” (which caused lesbians to desert it early on), to forge a new way of loving and struggle instead of replicating all the old crap:

We might have hoped that homosexuality could tear classic activism away from non-desire, inject it with a dose of epicurism and create a true celebration of our colluding desires, but that was without taking the bad conscience of homosexuals into account. We must admit that the wildfire was short-lived. . . . Here, we rebuilt the Leftist theater. There, we rebuilt the carnival of stars to assemble the next barricades in evening gowns. Theory for the sake of theory collided with madness for the sake of madness, and they both tried to reconcile themselves in the imperialism of youth and beauty. For, just as collectibles are deemed beautiful when old, bodies desired only as objects are only deemed beautiful when young. (26)

A key goal of gay liberation, Guy argues (along with many post-Stonewall gay activists), is not merely to seek more elbow room for a gay-identified minority, but to confront and help liberate the repressed homoerotic desires of everyone. This is gay liberation before a reformist identity politics replaced it:

Since we are not homosexuals in any elementary way, it is time to stop proudly shouting our shame. “You are homosexuals” is what we should be shouting out to all, even if we must become hysterical in the process. And since it is established that there can be no real bisexuality without homosexuality first being experienced as such, our revolutionary activity could be to cause, by any means possible, the homosexuality of the silent majority to germinate beneath its anti-homosexual paranoia. (47)

“Come out!” was the cry of the post-Stonewall rebels. It was also the name of the journal of New York’s Gay Liberation Front. The trouble is, when the closet doors were flung open and hordes of same-sexers came out in the late 1970s in response to the antigay crusades of Anita Bryant and others (making gay lib a mass movement for the first time), along with them came many bourgeois and moneyed folk who weren’t seeking revolutionary change or to challenge heterosexism, let alone capitalism. And with the decline of the Left as a whole, and along with it a gay Left, the early goal of sexual freedom for all was replaced by an agenda of assimilation into the heterodominant, bourgeois status quo.

Liberation is in conflict with identity politics and a strategy of gradualism. Gays, lesbians, and women’s liberation are all deluded insofar as they all “believe that the difficult pursuit of the non-differentiation of desire is politically premature, or that it is depoliticized and even tainted with mysticism.” He goes so far as to describe their refusal to expand desire and determination to defend their respective turfs as “the establishment of a series of counter-terrorisms that congeal and exclude one another. . . . All sexual minorities thus crystallize on their particular specificity.” He does not see “such atomization” as a necessary stage during which “the margins encircle and encroach upon normalcy in a thousand different ways,” because “the margins should not combat the margins, for this will just strengthen normalcy” (58-59).

His critique of identity politics (a term not yet much in use) is relentless because it serves to thwart a “broadening of desire”: “Limiting oneself to a sexual path, under the pretext that it is one’s desire and that it corresponds to a political opportunity for deviance, strengthens the bi-polarization of the ideology of desire that has been forged by the bourgeoisie” (60). He dismisses the fear of the “touchy nationalists of homosexuality” that they “will lose their sexual identity” if his broader vision of sexual freedom and desire is pursued:

Desire must be allowed to function on any object. And not only on a body other than one’s own. And not only on one body instead of two or more, simultaneously. And not only on the age class of youth or on the esthetic class of beauty, the formal elements of the class struggle. And not only on one of the two phantasmatic modalities of masochism or masochism disguised as sadism. And not only on one of the two sexes. And not only, assuming these differentiations will eventually disappear, on the human species. (60)

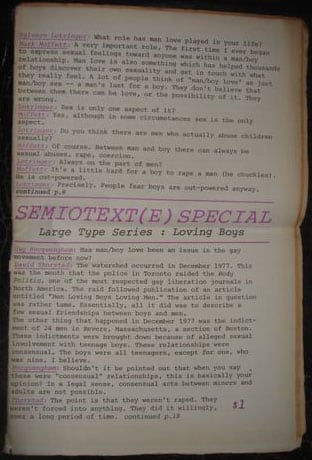

Guy lived in his personal life the kind of nondifferentiated sexual desire he saw as a potential future achievement of the sexual liberation struggle. As he says in this essay, he loved boys passionnément (a word left untranslated), even as he sought to embrace the Other and welcomed ambiguity and fluidity in interhuman relations. In 1980, he interviewed me for the Semiotext(e) Special newspaper Loving Boys, an underground classic (“large type series for people with unlimited vision” — a take-off on the New York Times large-type editions for the near-blind). He mentioned during the interview that he had recently decided to get circumcised. I found that confession of voluntary mutilation surprising, and asked why he had done it. He said that he preferred Arab youths (cut, of course) and that “I’ve spent half my life uncircumcised, and wanted to spend the second half cut.” I asked if I could see it. He cheerfully pulled down his pants and displayed it, and, spontaneously, we made love. Sperm of the moment, so to speak, a transcending of preferences and identities in mutual sharing.

The second half of Guy’s life was cut short just eight years later. His passing was a blow to a movement that lost an irreplaceable voice.

A note on the translation: The book is not an easy one to translate, starting with the French title: Les culs énergumènes. Culs means either “asses” or “assholes.” The latter might be closer to Guy’s intent (“asses” connotes stupidity, and that’s not the meaning here). The word énergumène is difficult to render in English. It can have a mildly derogatory flavor, and is often used to refer to someone who is eccentric, outrageous, or quite a character. Other meanings are of a higher order than “screwball” (which inevitably evokes “screw” and “ball,” neither of which has anything to do with énergumène), and suggest possession by demons, overly excited, even fanatic, exalted. One can sympathize with the translator’s difficulty.

Another problem is not resolved so well, and that is the word pédé, short for pédéraste, but not limited to the narrow meaning of “pederast” as it is in English. In French, it was used by gay activists to mean “gay” (and male). Here it has usually been translated as “queer” (occasionally as “gay”), but especially in light of the later development of “queer theory” and the now widespread use of “queer” to denote far more than simply a gay man (absurdly even potentially a heterosexual female), that translation is misleading and unfortunate (“gay” or “gay male” would be closer), as can be seen in the following quote: “The queer is a traitor whose greatest fear is betraying normalcy. And once he has overcome that shame, he realizes by betraying normalcy, what he did in fact was bow to it” (51). Here, “queer” distorts the meaning by its inevitable conflation with current (mostly academic) usage.

The name of the conservative group Arcadie is given as Arcadia in the following otherwise wonderful summation of Guy’s vision (perhaps confusing readers not informed about French gay groups from that period):

The gays in my dream, my lovers, my friends, my enemies and myself, we can no longer distinguish desire from what is called love. And in my dream we can experience the same joys with women. For I cannot imagine the dissolution of normalcy without the so-called intersexual states becoming universal. I see no other way to get rid of the tyranny of virility, a tyranny, it should be said, that oppresses men just as much as it does women. To demand the recognition of homosexuality as it exists today, colonized by heterosexual imperialism, is simply reformism. It is not for us, it’s for those good souls in Arcadia, at a birthday party, who invite the Police commissioner to the table of honor. (51)

The irony is that, four decades after Stonewall, this last reference — which showed the contempt of the seventies rebels for conservative assimilationists — might easily apply to most mainstream gay and lesbian organizations.

1 Jeffrey Weeks, Preface, in Guy Hocquenghem, Homosexual Desire, trans. Daniella Dangoor (London: Allen & Busby, 1978), 19.

David Thorstad is a former president of New York’s Gay Activists Alliance, a cofounder of the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights, a cofounder of the North American Man/Boy Love Association, coauthor of The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864-1935), and editor of Gay Liberation and Socialism: Documents from the Discussions on Gay Liberation inside the Socialist Workers Party (1970-1973). His writings are available at <www.williamapercy.com/wiki/index.php?title=David_Thorstad>.

var idcomments_acct = ‘c90a61ed51fd7b64001f1361a7a71191’;

var idcomments_post_id;

var idcomments_post_url;