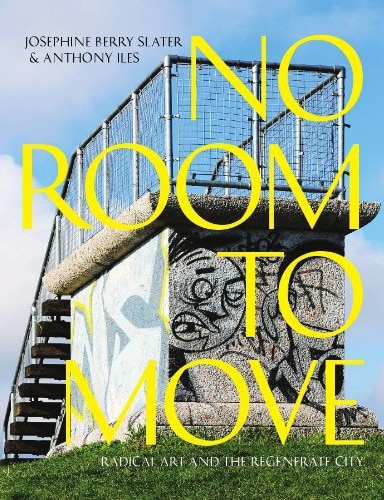

Josephine Berry Slater and Anthony Illes. No Room to Move: Radical Art and the Regenerate City. Mute Books. 124 pp.

“Gentrification was already coming. The feta-cheese footprint.” — Stewart Home

Broadway I

Located on the historic drovers’ road that led from Essex to the slaughterhouses of Smithfield, Broadway Market in Hackney is one of the oldest chartered markets in London. On a pleasant Saturday it can be an attractive place to linger. Beautiful twenty and thirty somethings sail by on vintage bikes, stop to buy a stalk or two of wildly overpriced asparagus, a chunk of cheese from the Pyrenees, drink a coffee at one of the attractive continental style cafes and check each other out for the flâneur thrill of it. Walking here in this fantasy world, paradoxically located within what is still one of the poorest boroughs in Britain, you could be forgiven for momentarily forgetting that the global economy lies in tatters. This is a Disney Land, a place for lotus eaters, but it is also the site of a conflict that has revealed the ravaged painting in the attic of Hackney Council, and in broader terms delineates the problematic issues surrounding regeneration.

On the wall of one of the most popular cafes here, just below the sign that gives customers the wifi code, there is a black and white photograph of the market as it was in the early 1980s. It looks a very different place; a morose woman holds a limp bunch of flowers she has just purchased from one of the few rickety, rain battered stalls, a couple of equally limp grocers’ shops line the street amongst many more that are boarded up and plastered over with for-sale signs. It’s a far cry from the bijou world of organic butchers, art book stores and glittering new estate agents that line the market now.

And why is this photograph here? It seems incongruous among the bowls of Provençal olives and the pyramids of Valençay. It opens up a feedback loop between fantasy and authenticity, present and past. On the one hand it reminds the boho-lite cash cows who shop here that they live in the ‘authentic East End’ of jellied eels, barrow boys, violence and misery, it gives them a sniff of the romanticised urban working class community that once defined this part of London, on the other hand it comforts them by safely containing the nightmare of the past, it’s history and everyone knows history has no bite to it anymore, right?

In 2001 Hackney council did its books and found a 72 million pound hole in its finances and was told by central government that the game was up and ordered to plug the gap by selling off large swathes of its commercial property portfolio. Within 28 days shop-keepers on Broadway Market were notified that the properties in which they ran their businesses would be sold to the highest bidders to achieve what the council called — while paying no heed to the possible social and ethical connotations of the term — ‘best value’.

The street is now effectively owned by three large property developers: Roger Wratten — a former Citybank dealer — and two offshore interests, one called Broadway Investments Hackney, which is registered in the Bahamas, the other with a Moscow postcode.

Here is an example of the irony of the globalised context in which we now find ourselves. Broadway Market is touted as a local success story, a market regenerated by locals for locals, that sells cheese made in the south of France to people born in Surrey in shops owned by a property investment company based in the Bahamas.

Broadway II/Mute I

“Art is attached to the bourgeoisie by an umbilical cord of gold.” — Clement Greenberg

Among the many shops that line the market are two excellent art book specialists; Donlon Books and the lackadaisically named Art Bookstore, there is also a non specialist place, Broadway Books and there’s an independent DVD rental outlet that specialises in art house and foreign language cinema. All this reflects the artistic milieu of the street and the surrounding area and inevitably leads one to question the role artists have played in the process of regeneration.

The story is a familiar one; artists and other so called ‘creatives’ move into a deprived area in order to gain cheap rents, they bring a fairy-dusting of bohemian glamour and then open the floodgates for property developers to move in, buy everything up and hike the rents. Locals are often forced out. It’s a story in which artists — perhaps because of their reputation for otherworldliness — are often portrayed as blameless dupes, but what if the story was not that simple, what if some were not duped at all but were actively allowing themselves to be used to inculcate a neoconservative entrepreneurial urban social model?

In both the art book stores mentioned above one can pick up a copy of Mute Magazine, which has just had 100% funding withdrawn under the Conservative party’s austerity measures for the arts. It’s a radical journal that ‘invites its readers and writers to consider new possibilities for resistance to hegemonies wherever they find them, from socio-economic and technical structures, to codes of representation and enunciation, to the production and articulation of psychic experience and beyond.’ It’s not difficult to see why the Conservative party might not be favourable to such an organ.

|

You can also pick up a copy of a book Mute published recently entitled No Room to Move: Radical Art and the Regenerate City. The book contains a critique of the regeneration model of urban development followed by several field interviews with artists whose work questions, satirises or mimics the so called ‘creative city’ model.

As the book explains, the roots of the regeneration concept evolved out of ‘gentrification’, a term coined by the sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964 to describe the movement of affluent individuals into less than affluent areas. Initially the process seemed to evolve organically, but over time it has become increasingly engineered by ‘at first local and now global networks of real estate developers and speculators. The outcome of gentrification is usually increased property prices, increased revenue to local governments from property taxes and the displacement of the local population.’

This engineering has often involved artists, indeed Stirling Ackroyd, an estate agents based in Shoreditch, specifically targeted adverts for short life live/work leases at artists (whom they cynically termed scuzzers) in order to stimulate growth in the rental market and attract property investment into the area.

No Room to Move locates the difference between gentrification and regeneration in the latter’s unique levels of state involvement. Regeneration is the attempt to stimulate gentrification through the establishment of ‘quasi-state agencies, tax breaks, re-zoning, public subsidy of private development, the privatisation of local resources and the deployment of culture.’ It’s defined by the state’s involvement in a form of voodoo economics:

Modelling themselves on the ideal of a self organising free market, regeneration agencies have sought everywhere to maintain the illusion that the market is the driver of positive change. Underfunded by central government and bombarded with neo-liberal ideology, local councils have executed something like the IMF’s structural adjustment programmes upon themselves, transferring council housing, schools and leisure services into private hands.

The problem is that the model of culture led regeneration developed under New Labour (the building of galleries/life style palaces, the commissioning of monumental public sculpture to signal a down at heel area’s emergence as a new cultural bastion, the use of artists as softeners for real estate buy ups) has been shown to be a chimera in light of the financial crisis. The state is underwriting market based solutions rather than investing in atrophied public services, state intervention has merely shifted its ideological mask. ‘The State bankrupts itself to make it seem as if the market is working’.

Culture led regeneration reached its zenith during the New Labour years but it originated, like so much Blairite ideology, in Thatcher’s Britain. In 1981 civil unrest erupted in the form of riots across the UK. In London (Brixton), Liverpool (Toxteth), Birmingham (Handsworth) and Leeds (Chapeltown). The local issues in each case were nuanced but the central issue was the same, poor inner city communities felt victimised by the state and saw the police as enforcers of the its will, not protectors of the people. The then Secretary of State for the Environment, Michael Heseltine toured the cities in the aftermath of the urban dissent and his solution was to focus on culture and sport as a band aid. He was inspired by West Germany’s post war Bundesgartenschau (BUGA), biannual garden festivals which were extremely effective in the process of regenerating Germany’s crippled post war cities. However Heseltine failed to recognise that the success of these festivals and the attendant white goods revolution they inspired was underwritten by vast American investment on a level the UK could never hope to match.

None the less, five festivals were held in Britain, in Liverpool, Glasgow, Gateshead, Stoke-on-Trent and Ebbw Valley. They were social and architectural failures, in each case the sight was left derelict or in the hands of developers who bought them up. However, ‘they would become a success story for capital in the medium to long term as new areas of development were opened up, planning laws waived and land remediation costs paid for by the State.’

|

Heseltine was also responsible for the setting up of a number of Quasi Autonomous Non Governmental Organisations (Quangos) to oversee the redevelopment of large parts of former industrial sites in the inner cities (including the Garden Festival sites). The largest was the London Docklands Development Corporation. No Room to Move locates the split in artists’ attitudes to regeneration to the LDDC’s establishment. Before it was set up, Docklands was an area inhabited by a militant working class of former dock workers and increasingly, from the late 70s onwards, artists and squatters attempting to set up a proto-punk Situationist community. As the LDDC implemented its redevelopment strategy the local community, artists and trade unions fought a bitter battle over the area’s identity. Artists Peter Dunn and Lorraine Leeson collaborated on the Docklands Community Poster Project (1981-1991) which involved the making of a number of large (12ft-18ft) billboard posters that were attempts to outline the issues affecting the community. They ‘highlighted the inequities of the deal the LDDC was offering to the [local] community and the interests of big business that lay behind it.’ Nothing, of course, changed.

On the other side of the equation was the emergent Young British Artists (YBA) phenomenon and in particular their ring leader, Damien Hirst. In the early stages of the Docklands development many artists had studios leased from the LDDC through ACME studios. When Hirst was attempting to put on his now famous Freeze exhibition he turned to the LDDC directly who allowed him to use a warehouse belonging to the Port Authority of London in Plough Lane.

Hirst had a natural ability to find the sources of money and wealth and was able to align his art with government policy. This ultimately led to Blair’s rebranding of the entire nation (and particularly the capital) as Cool Britannia. Hirst and the LDDC together formed an ad hoc model for how government, big business and art could work together and this led to the instrumentalisation of art in the regeneration project. Artists became increasingly professionalised and followed an entrepreneurial model that bloomed in the 90s mega art market. As No Room to Move points out a ‘structural shift had taken place’ in the relationship between artists and free market capitalism.

And look where it has led us, in one year’s time the Olympics will be held not far from where Hirst held the Freeze exhibition and nightmares have been born. The Olympics is leading to Triumph of the Will type visions in many of our heads. Except this is not the triumph of Nazi ideology, but a neo-con model, a soft version of Naomi Klein’s shock doctrine. Foreign money is pouring in, particularly Russian, real estate is being bought up, everyone wants a piece of the action. The artists Anja Kirschner and David Panos made a film Trail of the Spider that satirises the Olympic land grab, described by Iain Sinclair as:

a Situationist spaghetti western shot on Hackney Marshes; where, the makers assert, the land-grab expansionism of the Old West ‘collides with suppressed history’. Range wars erupt along ‘a vanishing frontier, swarming with calculating surveyors, corrupt lawmen and hired thugs’.

This is the wild west, and of course at the heart of the Olympics demonstrations of drug fuelled athletic prowess there will be the ‘cultural olympiad’ with Anish Kapoor’s mangled Eiffel/Blackpool Tower-lite at the centre of it to remind us, like the young Nazis in Leni Riefenstahl’s film, to look up into the bright new dawn. We get the art we deserve perhaps, and it is blinding us.

John Douglas Millar is a researcher, critic, curator and writer living in London.

var idcomments_acct = ‘c90a61ed51fd7b64001f1361a7a71191’;

var idcomments_post_id;

var idcomments_post_url;