Intersectionality as a key concept in women’s studies has up until the present proven rather durable. Feminist journals are peppered with it and feminists use it pretty much without having to explain what they mean, the term’s affinity with feminism taken for granted and its import unquestioned. Attend any women’s studies meeting, and sooner or later you will hear “intersectionality” uttered like a mantra. Employed to refer to the intersection of gender, race, and class (although often expanded to include limitless other identities), over the years much ink has been spilled and several conferences devoted to debates and discussions about its merits and demerits, not to speak of attempts to pin down its precise meaning.

Among the more recent articles probing into intersectionality is one that assesses its value as a theory. Deploying a sociology of science perspective as her gauge, Kathy Davis arrives at the conclusion that the alleged weaknesses of intersectionality — ambiguity and open-endedness — are actually its strengths, the very reasons for its remarkable success. I single out this article because I believe that Davis’ embrace of ambiguity and open-endedness is currently shared by a majority and is symptomatic of what I (and others before me) view as the dismal state of feminism today, particularly as expressed in the academy. Situated in colleges and universities increasingly corporatized since the Reagan/Bush administration, contemporary feminism has lost its radical edge and speaks mainly to those schooled in its arcane language. This deradicalization, however, must not be perceived purely as a failure of individual feminists but as a consequence of the accommodation to reigning neoliberal ideologies that the academy as a whole has been compelled to make, a move made easy by the absence of a robust social movement. In short, the changes we see in feminism simply mirror those in the academy that are themselves reflections of the ongoing transformations in the larger society. The United States is clearly not the same place today as it was during the social ferment of the 1970s; perhaps more to the point, intellectual life and the thinking of the general public have been profoundly altered as well.

With such a context in mind, I trace the roots of intersectionality as a theoretical approach back to the notion of “triple jeopardy,” a slogan hoisted by Third World women — who, it should be noted, initially refused the label “feminism” — at the peak of the women’s liberation movement in the early 1970s. It is true that it was critical race scholar Kimberle Crenshaw who introduced the term in 1989. But to begin with Crenshaw suggests a certain intellectual laziness, a narrowness of mind that only checks into the word itself and not its conceptual origins. Confining its inception to an already professionalized feminism erases the historical fact that its conceptualization was actually honed in the intensity of revolutionary struggle by women-of-color organizations. It likewise obscures the historical fact that women’s studies came into existence only because of the clamor out in the streets by women’s liberation activists.

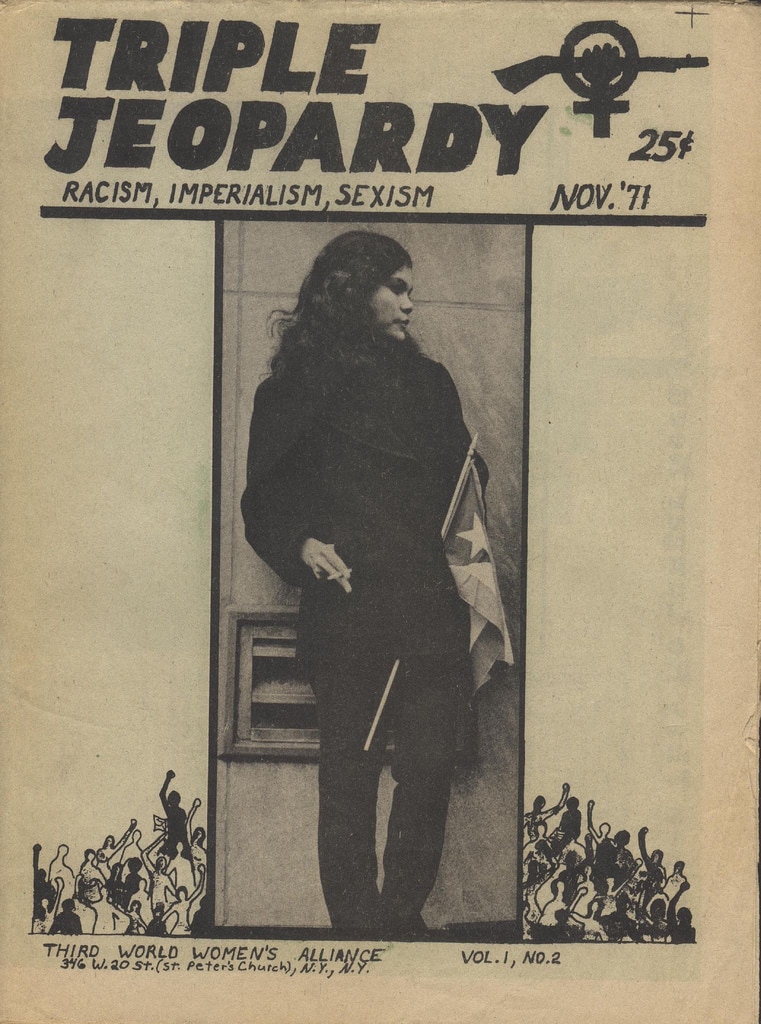

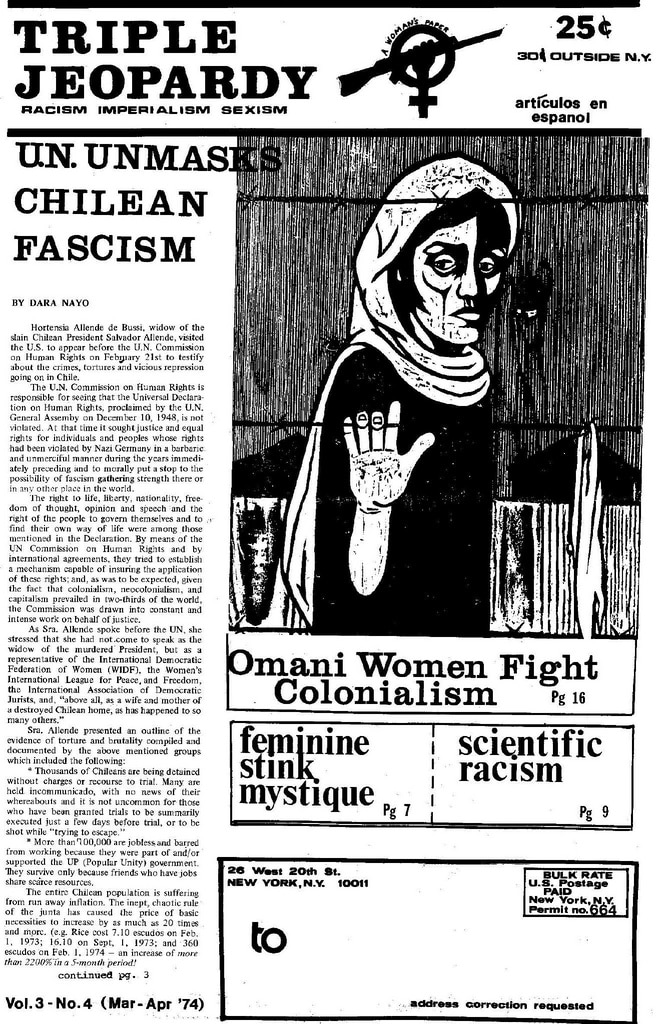

I believe that a recuperation of this aspect of second-wave feminism’s history is necessary if we are to comprehend the present in which vagueness and ambivalence has become a virtue. In the euphoria of the discovery in consciousness-raising sessions that dissatisfaction with their lives rested not in themselves but in gender arrangements, white middle-class women projected their own specific experiences of subordination as universal. This was immediately resisted by women on the margins. “Third World” women (a designation used by women of color who assumed the reality of an “internal colony”), taking their cue from Vietnamese women freedom fighters, asserted the existence of a “triple jeopardy.” By this they meant three systems of oppression: sexism, racism, and capitalism or imperialism. Among the groups taking this stance was the Black Women’s Alliance in New York City that later united with Puerto Rican women to set up the Third World Women’s Alliance in 1970, an organization that became a major player in 1970s activism. The Alliance presented their views in a newsletter titled “Triple Jeopardy.” Subtitled “racism, imperialism, sexism” (in this order), it displayed a fist and rifle inscribed on a woman’s symbol at its masthead. The newsletter covered a wide range of issues including welfare, analysis of the US class structure, struggles of women in China, Guinea Bissau, Chile, and so on.

The jeopardy motif was simultaneously pursued by others seeking to develop the concept. The first was Fran Beale who in 1969 wrote “Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female,” where she details the specificities of Black women’s lives in capitalism, emphasizing their location at the bottom of the social relations of production. Taking off from Beale’s polemic, “A Black Feminist Statement” written in 1977 by the Combahee River Collective (with Barbara Smith as the main author) stands as a major document in women’s liberation history. Like Beale’s period piece, it expands liberal feminists’ “personal is political” stance by adding race and class, and moves the jeopardy thesis forward by describing multiple oppressions as both “simultaneous and interlocking.” The Combahee Statement enjoyed broad circulation and discussion in women-of-color as well as leftist women’s liberation circles. But it was not until the publication in 1981 of This Bridge Called My Back that mainstream feminists’ attention was captured by the writings of women of color. Edited by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, the book broke new ground by testifying to the struggles of women who were Latina, Black, Asian, and Native American. The anthology — most of the pieces were highly subjective and personal — immediately became required reading for women’s and ethnic studies courses. What the book dramatized was the intersection of gender, race, and class minus the anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist perspective consistently invoked by previous manifestos on “jeopardy.” Its extensive adoption notwithstanding, its impact on feminist theory-making turned out to be primarily cosmetic, Norma Alarcón, a contributor to the anthology, was to complain nine years later.

The last and in my opinion the most important contribution to the race, class, and gender-inflected works during this period of revolutionary ferment was the book by Gloria Joseph and Jill Lewis in 1981, Common Differences: Conflicts in Black and White Perspectives. Joseph, a Black woman, and Lewis, a white British, witnessed the antagonisms over race and class that were wracking the movement at the time. Even as Black women (“Black” used as a stand-in for women of color) railed against gender disparity within the ranks of Black liberation, they were not flocking to the women’s movement. The book was an attempt to find out why, by turning to their respective communities for answers. Joseph and Lewis compared and contrasted their findings in the following areas of investigation: attitudes toward the women’s liberation movement, mother-daughter relationships, and sexuality and sexual attitudes. All throughout they make explicit their ideological framework. They do not waiver in implicating the power exerted by multinational corporations in the capitalist United States and how their profit-seeking impels adventures abroad — in a word, imperialism.

From this point on, there is a pronounced change in the works that emerged expounding on the themes of gender, race, and class. The view that a meaningful exposition of their interaction demands an understanding of capitalist operations was soon to be swept away by the collapse of social movements and the onset of conservatism. By the mid- to late 1980s, conservatism was becoming entrenched, necessitating adjustments in intellectual perspectives in order to remain au courant in an increasingly complicit academy. In 1989 the Soviet Union would collapse, causing progressives to lose sight of an alternate vision. These events were not without impact on feminism. This impact is already evident in Deborah King’s essay, “Multiple Jeopardy, Multiple Consciousness: The Context of a Black Feminist Ideology” written in 1988. Her strategy is to attack “monism” which she marshals against Marxism as well as against all liberation politics, be they feminist, racial, or class movements. Double or triple jeopardy, she maintains, were steps in the right direction except for the fact that they were additive, hers being “multiplicative.” We are observing here a profound shift. If This Bridge Called My Back transported the systemic analysis of double and triple jeopardy into the realm of experience, multiple jeopardy has turned this into ideologies that produce multiple consciousness. Soon to follow, in the hands of bell hooks and Patricia Hill Collins, “multiple oppressions” — the notion of “class” now merely designating income, occupation, or lifestyle detached from mooring in the social relations of production — became embedded not in capitalism but in “matrices of domination.” At this point, we have effectively moved to the realm of discourse with less and less material anchor. The way has now been paved for intersectionality as we know it and as Kathy Davis extols it.

As the earlier antecedents of intersectionality make perfectly clear, it was the fertile ground of the women’s liberation movement that enabled feminists to collectively conceive nothing less than societal transformation as their ultimate goal. With the decline of social movements and the deliberate harnessing of intellectuals in the service of capital, feminists, now tethered to academic concerns, have traded clarity of analysis and purpose for ambivalence, obscurity, and mystification.

References

Beale, Fran. 1970. “Double Jeopardy: To be Black and Female,” in Robin Morgan, ed., Sisterhood Is Powerful: Anthology of Writings from the Women’s Liberation Movement. New York: Vintage Books, 340-353.

Collins, Patricia Hill. 1991. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York: Routledge.

Combahee River Collective. 1981. “A Black Feminist Statement,” in Cherie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua, eds., This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. MA: Persephone Press.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43.6: 1241-1299.

Davis, Kathy. 2008. “Intersectionality as Buzzword: A Sociology of Science Perspective on What Makes a Feminist Theory Successful.” Feminist Theory 9.7: 67-80.

Joseph, Gloria and Jill Lewis. 1981. Common Differences: Conflicts in Black and White Perspectives. Boston: South End Press.

King, Deborah. 1988. “Multiple Jeopardy, Multiple Consciousness: The Context of a Black Feminist Ideology.” Signs 14, 1, 42-72.

Moraga, Cherrie and Gloria Anzaldua. 1981. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. MA: Persephone Press.

Triple Jeopardy. <www.flickr.com/photos/27628370@N08/sets/

72157605547626040/>.

Delia D. Aguilar has written extensively on feminism and nationalism, among them a book titled Toward a Nationalist Feminism published in the Philippines. She is a co-editor of Women and Globalization (with Anne Lacsamana).

| Print