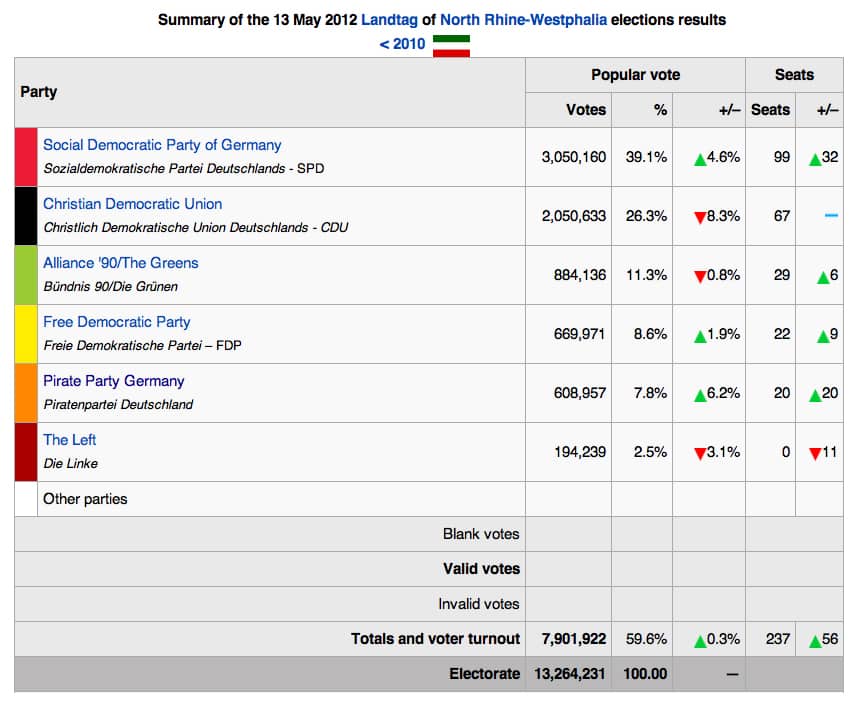

Here’s “good news” and “bad news” from Germany. The good news: the Christian Democratic Union of Angela Merkel took a real whipping in the election in North Rhine-Westphalia (usually abbreviated to NRW), the largest German state in terms of population. Her smiling, almost benign mien, with little bluster or braggadocio, disguises less and less her tough advocacy of austerity — a code word for overcoming deficits not by hitting big banks and big business, who caused the calamity, but rather the people who have always been hit worst and who are truly suffering. Americans may recall Congressman Paul Ryan’s cruel recipes; they are closely related. But the election of François Hollande in France, the current tumult in Greece, and demonstrations all over Spain, in Italy, even in London have shown what many ordinary people think of such austerity! Now, sixteen months ahead of next year’s national elections, her party took the worst beating in its history in this key state, NRW, which has more people than all of East Germany. Her major opponents, the Social Democrats, were greatly strengthened, their partners, the Greens, held their own, and, for better or worse, the two will now have full sway there.

As for the “bad news,” not all of it is world-shaking. The first item involves plans to open the giant new Willy Brandt airport of Berlin on June 3rd as a match for rivals at Frankfurt and Munich. The ballyhoo was immense for a project fought over for decades. Recent TV coverage centered on the amazing planned overnight switch from the pleasant little Tegel airport in the northwest of the city to the huge new site in the southeast, 20 miles away, without missing a flight. It was overwhelming — until it was canceled, just four weeks ahead of the opening date. The fire alarm and evacuation systems were not quite ready, it was claimed, and, after all, safety must come first! But it soon became almost certain that the big construction consortium had known for months that deadlines could not be met but hoped for a miracle and kept its collective mouth shut — until last week. Poor Mayor Wowereit, officially the top official in charge, looked very pale, and the postponement will cost many, many millions from the airlines, the retail shops, and the transportation companies. At first, August was offered as a new opening date, then there was talk of October — or maybe December?

A second blow for Berliners was in the offing: the almost certain loss of major league status for its main soccer team. For some, bitter tragedy! Every year the two worst teams out of sixteen drop to second league status while others move up. Only a miracle can save Hertha BSC. If there is none in one final game, then Berlin, Germany’s biggest city, will be the only major city with no team in the major league, at least until next year. And how shameful!

Source: “North Rhine-Westphalia State Election, 2012,” Wikipedia |

But alas, there was a far more serious bad news item, though all too few realized its significance. The aforementioned election in NRW, which scratched Merkel, seriously wounded its other main loser, the Left Party. It was no surprise in view of recent polls, but a shock all the same! It not only failed to reach the five percent needed to keep any of its seats in the state legislature (it won 11 in the last election) but lost severely, getting only about 2.5 percent! This was the second West German state in a week, after Schleswig-Holstein, where it lost its representation by missing the hurdle, and this state, due to its size, is especially important. It is hard hit by an economic crisis worsened by constant shutdowns of coal mines and steelworks in its Ruhr Valley, a real German Rust Belt. Why did these troubles, with severe cutbacks in the budgets of nearly all towns and cities, not work to the advantage of the Left? And why is this important, even to people in other countries?

Of course the media played a big part in this defeat: except for the very limited leftwing press, largely unavailable in much of the country, TV and printed media have a uniform strategy towards the Left. Except for occasionally playing up internal squabbles or problems, real or contrived, they maintain silence about the party’s actions and activities. In NRW the Left played an important part in preventing college tuition charges, improving free childcare possibilities, fighting for more financial help for local communities, and on many levels town and county councilors of the Left Party have been truly valiant. But all this was ignored while the catchy new Pirate Party was treated to almost daily pageantry, although it still has virtually no program, and it reaped the rewards at the polls, receiving over 8 percent. But this treatment was neither new nor surprising. It was sad that the Left has not been able to spite this media embargo and squeeze into positive public view via the Internet, all digital channels, and, most importantly, with eye-catching, media-challenging actions and activities in the cause of working people, young people and pensioners, immigrants and other disadvantaged groups. Bucking the media is never easy, but constant efforts — like Occupy — sometimes take effect.

But most commonly cited as the cause of the alarming weakening of the Left after its hopeful successes a few years ago was the inner quarreling which consumed so much energy and provided the media occasional welcome scandals. The fighting party program agreed to almost unanimously in Erfurt last October would, it was thought, heal wounds and break barriers. But it did not. Now, after defeats in two West German states, there are fears that the coming congress in early June in Gottingen, when a new slate of officers is to be elected, may not improve the situation.

The conflict involves personalities but, more than that, aims and strategies. The only person thus far to offer himself as candidate for co-president in June is Dr. Dietmar Bartsch, the unusually tall deputy chair of the Left caucus in the Bundestag. Bartsch represents the large, mostly East German sector of the party, which still averages between 15 and 30 percent in the five East German states, the former GDR, and shares in the government of one of them, Brandenburg. This broad base is important as a financial and voting percentage base for the party as a whole. Its leaders, like Bartsch, often called reformers, are in essence pragmatists. “We want progressive reforms in the social system; we must fight for the social benefits now being cut by the Christian Democrats and their coalition partners, the Free Democrats. To achieve success in this direction we must be ready to ally with two other parties now in opposition, the Social Democrats and the Greens. Sometimes we can join with them in a state government; and it may be possible, it is implied, that after next year’s national elections those two parties will need our votes to get over 50 percent of the deputies and gain power. With such hopes at all levels, we must be reasonable in our demands and do as little as possible to antagonize possible future allies. Frequent rejections of any cooperation with us can be seen as election propaganda.” Or so runs their reasoning.

Those opposed to the reformers claim that by being so reasonable, and by downplaying or abandoning main principles, we move so close to the Social Democrats that voters will see no real reason for choosing us instead of them. One basic principle involved is a strict refusal to send German troops anywhere outside Germany and withdraw them from their present deployment in Afghanistan and near the coasts of Lebanon and Somalia (with a newly expanded mission of hitting those pirates over land as well as over sea!). The Social Democrats and Greens have approved foreign deployment and insist on such approval; the “fundis” — or fundamentalist Left — adamantly reject it; the pragmatist reformers would agree to a position of “maybe, sometimes, with possible exceptions.”

Related, but even deeper in its implications, the more radical fundis insist that repairs and restrictions on the banks and big business are only half-way measures; we must keep alive the goal of rejecting the capitalist system and replacing it with some form of democratic socialism. The reformers agree that the system is indeed dated, socialism must remain a goal, but a cloudy distant one, and for now we must just try to make the banking system work more justly and save social welfare achievements, working together with the other left-of-center parties. The retort to this is: once Social Democrats and Greens gain power, they always forget most social promises; in recent years they were responsible for painful cuts in many areas. Their leadership (though not always their membership) always leans towards accommodating big business, where many of their leaders land when they retire from politics. A key issue the Left must always uphold: there must be NO further privatization of state-owned utilities or housing.

A final issue: the reformers agree with all the other parties in decrying the East German GDR as a second dictatorship in Germany, after Hitler, to be condemned almost in its entirety. The more radical wing, on the other hand, says that the GDR did many bad things, it ultimately failed, but its history must not be simplified in black-white terms, it represented an attempt to break with capitalism and fascism and was able to achieve many good things, from jobs for everyone to free childcare, free medical care, and free education for everyone. Its undoubted lack of rights and even its tragedies cannot be equated with the crimes of the Nazis.

One co-president in the past two and a half years was Gesine Loetzsch, a popular leader with roots in an East Berlin borough. Her co-president, Klaus Ernst, was a union leader from Western Bavaria, not so popular in general. A general rule was more or less accepted: a double leadership — a man and a woman, an easterner and a westerner. Loetzsch recently resigned her job because of the illness of her quite aged husband and will remain only as Bundestag deputy. Ernst has not stated any plans, making Bartsch, as mentioned before, the only announced contestant as yet.

But looming over the scene in a way is the charismatic West German politician Oskar Lafontaine, one-time head of the Social Democrats and very popular in his home region of Saarland. It was to a large degree his work in the new Left Party which helped it gain the crucial support of five to ten percent of West German voters and thus put the party on the all-German map. He withdrew from leadership in 2009 to fight cancer — successfully, it seems. Will he stand for election in June as president or co-president? And if so, with whom? The gains he helped achieve are visibly disappearing. Is that because of his absence or because of the more “leftist” stance of many West German party leaders? Many reformer leaders in the East dislike Lafontaine, who has taken more fundi approaches on many questions. While losses were being suffered in West Germany, interesting local victories were won in eastern Thuringia, including the jobs of mayor of one well-known middle size city, Eisenach, and county leader in Nordhausen in the Hartz Mountain area. Like most East German Left leaders, however, they support Bartsch. It is as yet unclear whether the grass roots membership agrees or will be enthusiastic about Lafontaine if he returns to national leadership.

Interestingly, most victories in Thuringia were won by women, who are strongly represented at many levels. Perhaps the best known nationally is the East German leader and theoretician Sara Wagenknecht. Once head of the Communist Platform group within the Left but in the past two years one of the deputy vice-presidents, she is a convincing speaker and writer. But she also became Lafontaine’s partner in more than just a political sense. Some think that the liaison has moved her ever so slightly towards a less militant position while moving him somewhat leftward. Their relationship would seem to make a joint presidency look more than awkward. It has however supplied grist for many of the media, almost their only reporting on the party for a while.

To sum it up: the coming congress in a few weeks can decide not only whether the Left party moves closer to the Social Democrats and Greens or to a more fundamental opposition, which would be more in tune with many active younger people like those in the Occupy groups. It may even determine whether the party moves closer to a split and thus the downfall of an imposing attempt to shake up German politics. Or can it find new paths to an active, aggressive fight for the rights of the majority of Germans and a move away from Merkel’s austerity and military mobilization policies? With Germany the strongest power in Europe (possibly excepting Russia) and one of the strongest economic forces in the world, and with the Left very important to many leftwing parties in Europe, the outcome can have a significant effect on future developments everywhere.

Victor Grossman, American journalist and author, is a resident of East Berlin for many years. He is the author of Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany (University of Massachusetts Press, 2003).

| Print