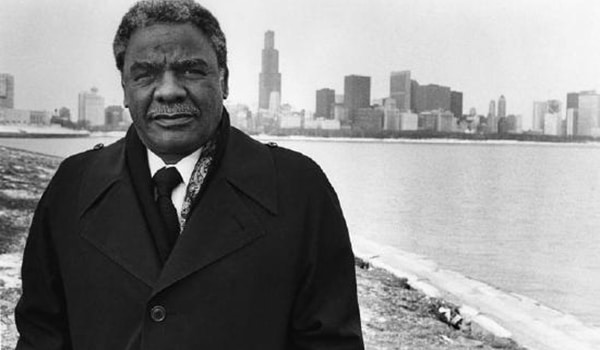

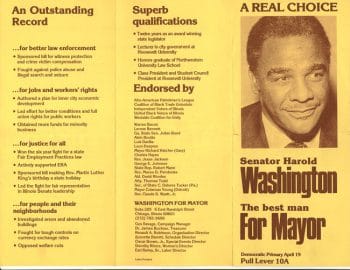

Nearly three decades after his untimely death, Harold Washington’s time as mayor of Chicago offers important political lessons for current progressive activists and organizers. While he ran for office as a Democrat, Washington was, in effect, drafted by a grassroots movement that emerged from the city’s neighborhoods. He only agreed to give up his congressional seat and enter the mayor’s race after supporters worked to add thousands of people to the city’s voter registration rolls while raising thousands of dollars in campaign seed money. What emerged from Washington’s run was a two-way process bringing together the “politics of the suites” and the “politics of the streets.”

Harold Washington became Chicago’s first African-American mayor in 1983, in part, because incumbent Jayne Byrne and fellow opponent Richard M. Daley, whose father had controlled the city’s political machine for two decades, split the white Democratic primary vote. In what was by far the most expensive mayoral election in Chicago’s history at the time, Washington won despite being outspent 5-to-1 by Daley, and by a whopping 20-to-1 by Byrne. However, his win was made possible by a populist campaign that spurred black voters to an almost 80% turnout and gave him 85% of their votes.

The political configuration of Chicago almost assured that the Democratic nominee would be victorious in general elections. In fact, no Republican had been elected mayor since the late 1920s. But Washington’s candidacy created a dynamic heretofore unseen. Racial animus fueled the campaign of his Republican opponent, seven term Illinois state representative Bernard Epton, who benefitted from the fact that many establishment politicians, favoring racial allegiance over party loyalty, jumped off the Democratic ship. In the end, Washington defeated Epton by four points, receiving 97% of a record turnout black vote in the process.

Washington ran pledging to open the political process to those who had historically been left behind. Upon taking office, he signed a decree eliminating patronage employment and proceeded to hold budget hearings throughout the city. Additionally, Washington used affirmative action procedures to increase the number of black and Hispanic employees in city government. White detractors like Jean Mayer, director of an ethnic neighborhood federation, as well as the new mayor’s city council nemesis Ed Vrdolyak, argued that change would largely consist of advancing minorities. But the approach from the beginning was dialectical: electoral and movement politics, insider and outsider strategies. For his part, Washington’s administration pledged to redistribute power and resources away from predominantly white downtown business interests and redirect them towards minority neighborhoods. For their part, activist organizations assumed responsibility for developing financial assistance proposals, reviewing city economic development policies, and implementing capital improvement programs. Admittedly, both the mayor and the activists defined city priorities in entrepreneurial terms, and their approach guided by populist principles was fraught with contradictions. But the goal was to move beyond a scenario in which a choice had to be made between pursuing either “the suites” or “the streets” to doing both with all the complexities and complications that would entail.

Political mobilization and organization operating outside of government yet linked organically to it worked to encourage policymakers on the inside. Results may have been less than hoped for, but they were achieved in the face of a white-dominated city council and under the scrutiny of white local media. While Washington lost his first two budget battles, some economic resources were shifted to neighborhoods, including funds for the creation of community cooperatives. And in granting citizen organizations the authority to review all city economic development programs as well as to submit economic assistance proposals, the mayor’s administration transferred a measure of substantive power as well.

Opposition notwithstanding, Washington redirected public funds to low-income residential districts and older industrial zones. Moreover, he successfully persuaded some private developers to invest in these areas as well. His administration gave priority to neighborhood infrastructural development projects, construction of affordable housing and increased employment opportunities. Towards such ends, city contracts were issued to minority and women-owned businesses. Together with the establishment of public taskforces intended to study various issues, these changes encouraged the continual mobilization of previously inactive citizens.

As Chicago politics shifted under Washington’s regime, some movement activists complained that community and neighborhood groups were moving away from confrontation with government. They argued that coalitions and alliances able to rely upon funding from City Hall led to a service orientation that did not challenge the status quo. According to left-oriented critics such as journalist and radio talk show host Lu Palmer and redevelopment corporation leader Robert Brehm, citizen organizations were becoming less defiant, their tactics more collaborative, and their operations increasingly client-like. While a useful reminder that incorporation can lead to institutional capture, such grousing fails to move beyond the old divide between inside government and outside it. What if, for example, the policymaking process was designed to bridge the gap between the two? On one hand, eliminate the built-in lack of access and influence that currently exists for those outside government. On the other hand, place citizen checks on those inside the corridors of power.

Washington’s coalition was tricky. Multi-ethnic identity politics, class consciousness, and good-government ideas did not always come together in productive ways. The mayor worked tirelessly to reduce tension between liberal do-gooders, socialists and black power advocates who were not always comfortable sitting in the same room. For example, Black nationalists supported a proposal to deposit city money in the Seaway National Bank, the largest African-American bank in the nation during the 1980s. In contrast, white lakefront reformers expressed concern that Seaway was small and vulnerable, and that placing public funds in the bank was too risky. Finally, socialists offered an alternative: establish a publicly owned municipal bank to handle the city’s financial resources. All the while, Washington was appealing to his opponents, often spending more time meeting with and speaking to them than he did his Rainbow alliance.

Harold Washington’s passing seven months after his 1987 re-election occurred before a more complete political transformation could be consolidated. His second term might have offered more room given that reapportionment had resulted in an increased number of allies on the city council. For example, only a week before his death, he issued a call for de-centralized and participatory education reform based on elected local school councils. The councils would be responsible for selecting principals, making budgetary decisions, and managing school affairs. But absent his presence, sharp divisions reemerged. Black nationalists were pitted against racial integrationists, middle-class reformers against working-class parents, white business leaders against the Black community, and the school board against community organizers. A bitter struggle for control of the city ensued between these various political factions.

Much of the change during Washington’s tenure as Chicago’s mayor was accomplished through executive action rather than the legislative process. Undoubtedly, the “stroke of a pen” is more vulnerable than is the enactment of laws. Consider the ease with which Washington-era reforms were largely abandoned. Six-term mayor Richard M. Daley, first elected in 1989, supported some Washington initiatives, particularly in the area of public education, but he used his office to rebuild patronage in city employment and contracting. Daley was initially persuaded to support Planned Manufacturing Districts (PMDs), a zoning mechanism intended to safeguard industrial production, factory employment and working class neighborhoods from gentrification. His administration, however, moved away from this effort in favor of high-end commercial and residential investment and development. At best, reforming Chicago’s historically corrupt and scandal-ridden political culture became an afterthought.

It is, perhaps, unfair to have expected the institutionalization of populist policies and programs in such a short period of time. And long-term change might not have occurred even if Washington had lived longer. Reliance upon individual leaders does not address how urban growth policymaking and the competitive character of global cities respond to the dictates of capital markets. Thus, proactive restructuring without popular mobilization will surely result in business as usual. Neither an episodic “politics of the streets” nor an incremental “politics of the suites” can by themselves overcome the conventional way of doing things. A convergence of the two is necessary to both combat political stasis and to develop an enduring progressive politics.