We spoke with Željko Cipriš, Professor of Japanese Studies at California’s University of the Pacific in Stockton, a city close to San Francisco. A New York publisher, Monthly Review Press, is about to bring out a selection from the works of Miroslav Krleža. Monthly Review Press is a notable publisher of socialist titles as well as of a magazine by the same name. It has published such classics—just to mention the most famous—as Monopoly Capital by Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy, and Labor and Monopoly Capital by Harry Braverman. Our source is a longtime professor of Japanese language and literature, and in the interview explains the motives for the publication in America of Krleža’s four stories, a one act play, a three-act play, and an autobiographical essay.

Whence comes the idea to translate Krleža’s work today and present it to American readers? In other words, are Krleža’s themes sufficiently universal and understandable to new generations?

Whence comes the idea to translate Krleža’s work today and present it to American readers? In other words, are Krleža’s themes sufficiently universal and understandable to new generations?

I’ve long been interested in left-wing writers. At the beginning of this century, I translated into English some works by a young Japanese man who worked in the 1920s, called Denji Kuroshima. Then I translated another Japanese radical writer, also a young man who was active in the 1920s and early 1930s, he is called Takiji Kobayashi. Then it finally occurred to me that I could translate something by the young Krleža too. Krleža is five years older than Kurošima and ten years older than Kobayashi; all three are almost the same age, more or less the same generation as, for instance, Bertolt Brecht or Antonio Gramsci. The seven of Krleža’s texts that I’ve chosen are all written in the 1920s, in the light of the recently concluded World War I and the October Revolution: The Battle at Bistrica Lesna, Barrack 5B, Guardsman Jambrek, National Guardsmen Gebeš and Benčina Talk about Lenin, Finale: Attempt at a Five-Thousand-Year Synthesis, Death of Prostitute Maria, and The Glembays.

At the time when he wrote these texts Krleža was a fiery, rebellious intellectual at the peak of activity. Although I respect the whole of his life’s work, this early period interests me the most. Of course, I hope it will be of interest to others as well: not only American readers but also those from various other countries who read English, but who previously might have never even heard of Krleža. I think that some of his themes, such as for example the ones in this book, definitely are sufficiently universal and understandable to new generations.

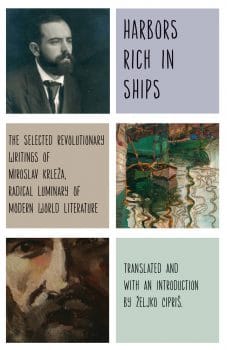

How is it that you are publishing Harbors Rich in Ships: Selected Revolutionary Writings of Miroslav Krleža, Radical Luminary of Modern World Literature with Monthly Review Press, a leftist publishing house? Nowadays domestic and European editors and publishers usually perceive Krleža as an author who writes about the collapse of the (non-)existing Croatian bourgeois class, and less, if at all, as a revolutionary or socialist writer.

First I sent a query to Northwestern University Press (they published The Return of Philip Latinovitz and The Banquet in Blitva), but they were not interested. Vanguard Press, which published The Cricket beneath the Waterfall, unfortunately no longer exists, and New Directions (On the Edge of Reason) does not accept new proposals. I tried two other publishing houses, but to no avail. The editor at Monthly Review promptly responded and asked me to send him the whole book, and only two or three months later we signed the contract.

Young Krleža, as we know, writes about imperialist wars, corruption, oligarchy, plutocracy, the miserable life under the dictatorship of capital, and so on. Moreover, he writes from the perspective of a revolutionary socialist. Almost a century later all of those Krleža’s early themes are still critically and tragically topical. Of course, various versions of ostensible socialism are today thoroughly discredited, but it could be said that socialism as such—in its authentic, humanistic version—remains a valid option for humanity.

From the previous question follows this one: Why did you at first title the collection The Glembays & Other Revolutionary Writings?

Given the fact that I consider young Krleža to be a passionate revolutionary, and see his work from that period as resolutely and deeply oppositional, the word revolutionary sounds appropriate. Once they accepted the book, the editors changed the title so it is now super-long and somewhat bombastic: Harbors Rich in Ships: Selected Revolutionary Writings of Miroslav Krleža, Radical Luminary of Modern World Literature.

To make the most of our conversation, we would like to ask you: In connection with the change of government in America, what is the current atmosphere? Have certain restrictions in your academic sector already become visible related to the arrival of the Republicans to power?

Although there are currently no signs of any restrictions in the academic sector (and let’s hope that there won’t be any), the atmosphere in the country is somewhat depressive. Obama was irresistibly charming, but of his promised hope and change (as some of us doubted from the start) there was almost nothing, neither in the domestic nor in foreign policy. Now we’re going from bad to worse. “Choice” in recent elections was tragicomically horrendous. Millions of Americans do not expect almost anything from either one of the two parties. It seems as if we are stuck in a neo-liberal deadlock. Perhaps it is unnecessary to add that comparable problems are not limited to the United States. How to break through to something new, discover a better and more rational way of social life? Such frustration and struggle against organized idiotism once again call to mind the torments and troubles against which our great writer fought almost a century ago.

Will there be a promotion campaign, and what are the customs pertaining to the presentation of a new book? Will the book be of interest only to the academic circles related to Slavic or South Slavic Studies, or will it also be experienced on a broader scope?

Since in the case of smaller publishing houses such as Monthly Review Press, and most university publishers, responsibility for the promotion of the book belongs more or less to the author (or translator), I’m trying to advertise Krleža’s “new” book wherever and as best I can. I’m sending short messages to each friend, writer, professor, activist, et al. who I think would be interested in the book. I’m also writing to departments of Slavic literature, bookstores across America, and across former Yugoslavia, ministries of culture, and others.

I am convinced that Miroslav Krleža is a writer of world caliber, whose work—timely and relevant—deserves to be much better known than it already is. I fervently hope that this book will be read by the broadest possible range of readers around the world, and that it will in a modest way contribute to human emancipation from an incorrigibly inhumane socioeconomic system. A fully achievable hope, is it not? Optimism of the will!