Nidesh Lawtoo: You are a political theorist but the kind of theory you are interested in is entangled with a number of different disciplines, from continental philosophy to anthropology, sociology to literary theory, stretching to include in-depth dialogues with hard sciences such as biology, geology, and the neurosciences. Across these disciplines you are known for your work on pluralism, for your critique of secularism, and for a conception of agonistic democracy that is inscribed in a Nietzschean as well as Deleuzian philosophical tradition. In your recent work, you have opened up this materialist tradition to the question of the Anthropocene. I am thinking of The Fragility of Things (2013) and, more recently, Facing the Planetary (2017), two books in which you frame your critique of neoliberal capitalism within larger self-organizing planetary forces such as glaciers and the ocean conveyor system that exceed market controls and force us to rethink conceptions of agency, intersubjectivity, the nonhuman, and politics in light of what you call “entangled humanism and the politics of swarming.”

Nidesh Lawtoo: You are a political theorist but the kind of theory you are interested in is entangled with a number of different disciplines, from continental philosophy to anthropology, sociology to literary theory, stretching to include in-depth dialogues with hard sciences such as biology, geology, and the neurosciences. Across these disciplines you are known for your work on pluralism, for your critique of secularism, and for a conception of agonistic democracy that is inscribed in a Nietzschean as well as Deleuzian philosophical tradition. In your recent work, you have opened up this materialist tradition to the question of the Anthropocene. I am thinking of The Fragility of Things (2013) and, more recently, Facing the Planetary (2017), two books in which you frame your critique of neoliberal capitalism within larger self-organizing planetary forces such as glaciers and the ocean conveyor system that exceed market controls and force us to rethink conceptions of agency, intersubjectivity, the nonhuman, and politics in light of what you call “entangled humanism and the politics of swarming.”

At the same time, in the wake of the 2016 presidential election in the United States, or actually already prior to it, you have been folding these future-oriented concerns with the planetary back into the all-too-human fascist politics that was constitutive of the 1930s and 1940s in Europe, but that is currently returning to cast a shadow on the contemporary scene in Europe and, closer to home, in the United States.

Genealogy of Fascism

As a response to this emerging political threat, last semester (spring 2017) you taught a graduate seminar at Johns Hopkins titled, “What Was/Is Fascism?,” which I would like to take as a springboard to frame our discussion. This title suggests at least two related observations: first, that fascism is a political reality that is not only related to the past of other nations but remains a threat for the present of our own nations as well; and second, that in order to understand what is fascism today it is necessary to adopt genealogical lenses and inscribe neo-fascist movements in a tradition of thought aware of what fascism was in the 1920s and 1930s. So, my first questions are: What are some of the main lessons that emerged from this genealogy of fascism? And what is “new” about this reemergence of authoritarian, neo-fascist, or as you sometimes call them, “new fascist” leaders that are now haunting the contemporary political scene?

Bill Connolly: That’s a good summary of what I am trying to do and of how this problematic on “What Was/Is Fascism” has emerged. Maybe the best way for me to start is to say that if you try to do a genealogy of Fascism your focus is on the present; the first thing that you pay close attention to is not just how things were, say in German Nazism or in Italian Fascism, but also how comparisons to those very different situations may help us to focus on new strains and dangers today. Another aspect of a genealogy of Fascism is to sharpen our thinking about what positive possibilities to pursue in the present. Current temptations to a new kind of Fascism might encourage us to rethink some classic ideals anti-fascists pursued in the past, asking how they succumbed then and what their weaknesses might have been. Some opponents of Fascism were inspired by liberalism, others by neoliberalism, and others yet by smooth ideals of collectivism or communalism. Neoliberalism—or its cousin, classical liberalism—helped to create pressures to Fascism when it ushered in the Great Depression, but perhaps neither of the other two ideals provides a sufficient antidote either. It is wise, in particular, to recall how leading neoliberal theorists accepted Fascism when they had to choose between it and socialism. Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman all decided to embrace Fascism as protection against socialism at key moments when market processes were under extreme duress. So, a genealogy of Fascism can help us to rethink ideals articulated in the past, testing their relative powers as antidotes to Fascism. And it can point to pressures that encourage advocates of other ideals to go over to Fascism. That’s part of what I hoped we could begin to do in this seminar.

Moving to the second part of the question: what are the dangers in the present that make some of us hear eerie echoes from the past? Well, a huge omission has been created in the Euro-American world, especially in the United States where my focus is concentrated. The neoliberal right has succeeded in pushing concentrations of wealth and income to an ever smaller group of tycoons at the top, while the pluralizing Left—which I have actively supported over the last forty years—has had precarious (and highly variable) success in its efforts to advance the standing of African Americans, Hispanics, women, diverse sexualities, and several religious faiths. There is much more to be done on these fronts, to be sure, particularly with respect to African Americans. But one minority placed in a bind between these two opposing drives—and the rhetorics that have sustained each—has been the white working and lower middle class. Portions of it have taken revenge for this neglect, first, in joining the evangelical/capitalist resonance machine that really got rolling in the early nineteen eighties and now in being tempted by the aspirational Fascism of Donald Trump. That has created happy hunting grounds for a new kind of neo-fascist movement, one that would extend white triumphalism, intimidate the media, attack Muslims, Mexicans, and independent women, perfect the use of Big Lies, suppress minority voting, allow refugee pressures to grow as the effects of the Anthropocene accelerate, sacrifice diplomacy to dangerous military excursions, and displace science and the professoriate as independent centers of knowledge and pubic authority.

So, that is where I want to place my focus: working upon earlier ideals of democratic pluralism to respond to this emerging condition. When I say emerging condition, I don’t mean that success is inevitable—the multiple forces of resistance are holding so far. I mean a set of powerful pressures on the horizon that must be engaged before it could become too late to forestall them.

Fascist Rhetoric

Nidesh Lawtoo: On this question of emerging conditions, you have been particularly attentive to the rhetoric neo-fascist leaders like Donald Trump have mobilized to win the election, an affective and infective rhetoric that many of us in the academia might have been tempted to downplay or dismiss for its apparent simplicity and crudeness—at least during the electoral campaign. But it has worked in the past and continues to be working in the present too.

In light of this genealogical reminder, you argue that critics and theorists on the left need to be much more attentive to the ways in which this fascist rhetoric—based on repetition, use of images rather than ideas, spectacular lies, but also gestures, facial expressions, incitation to violence, racist and sexist language, nationalism and so on—operates on what you call the “visceral register of cultural life.” I take this phrase to mean that the fascist “art of persuasion” is not based on rational arguments, political programs, or even basic facts. Rather, its aim is to trigger affective reactions that, as some precursors of fascist psychology (I’m thinking, of Gustave Le Bon and Gabriel Tarde, but also Georges Bataille, D. H. Lawrence and other modernist writers) also noticed, have the power to spread contagiously, especially in a crowd, but now also in publics watching such spectacles from a virtual distance. Could you say more about the affective power of this rhetoric, especially in light of a type of politics that increasingly operates in the mode of fictional entertainment?

Bill Connolly: That’s a really big question and it’s at the center of what I would like to try to do, however imperfectly. In preparation for this seminar, I read for the first time in my life, Hitler’s Mein Kampf. We explored huge sections of it in class, and I note that at first no students wanted to present on this book. I also note that almost no one I talked to, in the US and Germany (we’re having this interview in Weimar, Germany), had read that book either. The book was in large part dictated by Hitler to Rudolf Hess, while they were in prison together in the early 1920s. It reads as a text that could have been spoken: the rhythms, the punchiness, the tendency to lapse into diatribes in a way people sometimes do when they are talking…. What Hitler says in the book is that he spent much of his early life in politics rehearsing how to be an effective mass speaker; practicing larger-than-life gesticulations, pugnacious facial expressions, theatrical arm and body movements on stage to punctuate key phrases. The phrase/body combos in his speeches—we watched a few speeches—are thrown like punches: a left jab, a right jab, a couple more punches, and then boom—a knockout punch thrown to the audience! They are punches. Speech as a mode of attack; speech as communication set on the register of attack. Now acts of violence do not become big jumps for leaders or followers. In fact, as Hitler says, he welcomed violence at his rallies. His guards, who later became storm troopers, would rush in and beat up mercilessly protestors, doing so to incite the crowd to a higher pitch of passion.

If we think about Hitler’s speaking style in relation to Trump’s, it may turn out that Hitler was right about one thing: the professoriate pay attention mostly to writing; not nearly enough to the powers of diverse modes of speech. Of course, there are exceptions: Judith Butler is one and there are others. But writing and texts are what academics love to attend to, and styles of speech require a different kind of attention. If you read one of Trump’s speeches it may look incoherent, but it has its own coherence when delivered to a crowd. He also may rehearse those theatrical gestures and grimaces, walking back and forth on stage, circling around while pointing to the crowd to draw its acclaim, and so forth. When you attend to his speaking style you see that he has introduced a mode of communication that speaks to simmering grievances circulating in those crowds. Of course, he speaks to other constituencies too, some of them the super-rich. But the speeches are pitched to one prime constituency. His rhetoric and gestures tap, accelerate, and amplify those grievances as he seeks to channel them in a specific direction. Immigrants are responsible for deindustrialization, he says, never noting automation and free corporate tickets to desert the towns and cities that had housed and subsidized them so generously.

When Trump engages in the Big Lie scenario, which forms a huge part of his speeches and tweets, followers do not always believe the Lies. Rather, they accept them as pegs upon which to hang their grievances. So, when journalists ask, “Do you believe that he is going to build the wall and Mexico will pay for it?” many say, “No, I don’t believe that”. But when he says it, they yell and scream anyway because the promise is connected to their grievances. Trump is the most recent practitioner of the Big Lie perfected by Hitler earlier. Of course, the latter’s Biggest Lie was the assertion that Jews were themselves master demagogues of the Big Lie. That is exactly how Donald Trump transfigures the production of Fake News on right wing blogs; he charges CNN and the media in general to be purveyors of Fake News. The strategy of reversal is designed to make people doubt the veracity of all claims brought to them, preparing them to accept those that vent their grievances the most.

We have to understand how the Big Lie scenario works, what kinds of grievances it amplifies, how apparent incoherences in Trump’s speeches provide collection points to intensify grievances and identify vulnerable scapegoats—until people leave his speeches electrified and ready to go. They are excited when guards usher a protester roughly off the premises. As the crowd screams, Trump says: “Don’t you love my rallies?” Those on the pluralist and egalitarian Left have to learn how this dynamic works, rather than merely saying, “Those people are stupid if they believe those Big Lies.” That plays into Trump’s hands.

As to how the intertext between entertainment and politics grows, well, Trump was in entertainment as well as being a mogul in real estate where appearances and staging make up a large part of the show. Moreover, his Atlantic City investments pulled him closer to criminal elements, and he deploys gangster like tactics to cajole and threaten people. He moves back and forth between these venues. He is not the first one to have done so. Reagan did too. But Trump has perfected a new version of these exchanges, re-enforced by blogs and tweets.

Satirical Counter-Rhetoric

Nidesh Lawtoo: I would like to follow-up on this last point. You argue that it’s important to understand how this rhetoric works, but not in order to try to erase it. It’s rather a question of channeling it in new directions. This is a difficult maneuver for it implies sailing past the Scylla of a rationalist conception of subjectivity and the Charybdis of an authoritarian conception of politics: on the one hand, you don’t believe that we can transcend this affective or visceral register, for we are embodied creatures that are highly susceptible to mimesis and to the unconscious reactions imitation often triggers, especially in a crowd but not only; on the other hand, you also don’t believe that such affects can only operate from a top-down vertical principle whereby the authoritarian leader has total hypnotic control over the masses. It’s rather a question of promoting horizontal rhetorical alternatives that open up space for resistance, dissent, and political action. Within this configuration, and to reframe my previous question on the relation between fascist politics and entertainment, what do you think of the role a genre such as political satire or comedy plays as a counter-rhetorical strategy? As a non-US citizen who has lived in the US during several presidential elections I noticed how this genre is center-stage in American political, in a way people from other countries have often trouble to even imagine: From The Daily Show to The Tonight Show, The Late Show to The Saturday Night Show to the Last Week Tonight Show and many others shows that inform a big segment of the US population—in ways that, I must say, are more accurate and perceptive than so-called “real” news like Fox News. In a way, comedians seem ideally placed not only to understand, but also to unmask, and oppose Trump’s rhetoric on his own terrain. By training and profession actors rely on rhetorical skills that derive from the world of performance and operate on an affective, bodily register. And they do so in order to counter, horizontally, the vertical rhetoric of fascism—though I noticed their reluctance to use the word fascism in their shows—for that, genealogists are perhaps still needed… Anyway, I find it telling that specialists of dramatic impersonation (or actors) are now those who, paradoxically, unmask the fictions of political celebrities (or actors).

I value the work done on that front and I pay attention to it, but as I watch some of these shows I also have a lingering ambivalence and concern I’d like you to address. On the one hand, the rhetoric of satire effectively channels political grievances to unmask via comedic strategies the absurdity of the Big Lie scenario you describe as well as other authoritarian symptoms (nepotism, dismantling of public services, racist and sexist actions, dismissal of science etc.); on the other hand, comedy also seems to contribute to blurring the line between politics and fiction, generating an affective confusion of genres that could well be part of the problem, not the solution. Of course, satire has been around for a long time, but the promotion of politics as a form of mass-mediatized entertainment that saturates—via new media—all corners of private life seems relatively recent; and this fictionalization of politics, in turn, should redefine the critical role satire plays as well. In this spiraling loop the laughter comedians generate wittily exposes political lies, counters docile subordinations to power, promotes freedom of speech, and perhaps, in small doses, even offers a cathartic outlet that can be necessary for political activism. And yet, at the same time, I also worry that comedy could generate an affective demand—I’m even tempted to say unhealthy addiction—precisely for those political scandals (the sexist language and actions, the lurid tapes, the spectacular firings, the secret investigations, and so on) it sets out to critique, leading an already media-dependent population to paradoxically focus political attention on the leader qua fictional celebrity to the detriment of real political action itself. What is your take on this double bind? And how do you evaluate these comedic efforts to re-channel a visceral rhetoric contra fascist leaders?

Bill Connolly: I take an ambivalent approach to them, too. This is a very good question because my own perspective, which draws sustenance from your work on mimetic contagion in The Phantom of the Ego, is that certain kinds of stances that liberals often adopt, that deliberative theorists and others do too, in which you say that the visceral register of cultural life must be transcended; modes of politics that demean analysis, policy, rational argument and so forth are wrong-headed and have to be replaced. I too prize argument and truth. But I also believe that there is never a vacuum on the visceral register of cultural life, that this register—which can be affectively rich and conceptually coarse—is ineliminable. Infants respond to the gestures, facial expressions, laughter, movements and prompts of parents and siblings on the way to learning language, and this dimension of relational being never simply dies out. It constitutes the affective tone of life. But the visceral register can be engaged very differently than Trump does, as we move back and forth across the visceral and refined registers to pour an ethos of presumptive generosity into both. If we do not become skilled at this we open the door to authoritarians to fill the vacuum. Those of us on the Left need to find alternative ways to allow the two registers to work back and forth on each other, to be part of each other, so that our most refined beliefs are both filled with positive affective tonality and we are equipped to resist the Trumpian assaults. One thing neo-fascist rhetoric teaches us is the ineliminability of the visceral level of cultural life.

Some comedians—when they show you in amusing ways, as Saturday Night Life comics and others do, how Trumpian rhetoric, rhythms, gestures, facial expressions and demeanor work—imply that all this could be replaced with something entirely different. Well, it must be replaced, but not with something that denies the power of gesture and rhetoric, as those mirror neurons and olfactory sensors on our bodies absorb inflows below reflective attention. It is also necessary to examine how different sorts of bodily discipline encourage some modes of mimesis and discourage others. And so, I have an ambivalent relationship to comedians who do the exposes, depending on how they do it and what alternative they pursue.

The question is whether there are some who can carry us, as they show how the contagion works, to other rhetorical styles that don’t deny the complexity of life and that help to infuse refined intellectual judgments with an ethos of presumptive generosity and courage across differences in identity, faith, and social position. These counter-possibilities, then, need to be part of the comedy acts. Sometimes I think that people like Sarah Silverman and Steve Colbert get this while someone like the guy on Saturday Night Life may not. I’m glad that we’ve had these comedic interventions, so that people can look again at what is conveyed and how it is conveyed. But when responses take simply the form of name-calling, they incite more agitated segments of the white working and lower middle classes and teach us nothing about how to woo them in a different direction.

It’s a real quandary. I do not think that people like me, or others, now have the key to unlock this puzzle, but it needs to be thought about. Part of the reason it’s a quandary, again, is that there is never a vacuum on the visceral register of being, neither for the constituencies that Trump courts nor for the intellectuals and pundits who seek to pull these forces in different directions. Trump’s advantage is that it may be easier under conditions of social stress to drag people down than it is to lift them to a higher nobility. Cornel West, however, is a rhetorician who combines nobility, presumptive generosity and courage against aspirational Fascism. Trump is one of crassness and cruelty.

From the Crowd to the Swarm

Nidesh Lawtoo: You mentioned that this rhetorical register is particularly effective in a crowd, when people are assembled at rallies, part of a larger, more complex social unit. So, I would like to shift to a different but related topic. In your new book, Facing the Planetary, you have a chapter titled, “The Politics of Swarming and the General Strike,” which might make some readers wonder: What is the difference between a crowd and a swarm?

More specifically, in an individualistic culture centered on personal needs and desires, what are the strategies, or tactics, we could collectively mobilize to aspire to a political model of swarming that requires a degree of human collaboration that is sometimes instinctively present among certain animal species—the paradigmatic example of the swarm in your chapter comes from honeybees. I ask the question because Homo sapiens in the age of neoliberalism seems often, not only but often, restricted to playing the role of an individual, self-concerned, egotistic consumer, to put it a bit brutally. You, on the other hand, stress the need to learn to actively promote collaborative swarm behavior to collectively counter the multiple human and nonhuman threats we’re up against, as new fascist movements pull us deeper in the age of the Anthropocene. How to negotiate this contradictory push-pull?

Bill Connolly: In that book, which came out in February 2017, there are preliminary reflections about Fascist danger, but the focus is elsewhere. The focus is on how large planetary processes like species evolution, the ocean conveyor system, glacier flows, and climate change intersect with each other and generate self-amplifying powers of their own. Earth scientists have recently—between the 1980s and the 1990s—broken previous assumptions about planetary gradualism that earlier earth scientists such as the geologist Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin made with such authority. There have been several punctuations of rapid, deep change in the past well before the Anthropocene; now there is another rapid change created by capitalism, replete with a series of planetary amplifiers. Planetary gradualism has bitten the dust, but a lot of humanists and human scientists, even those who worry about the Anthropocene, have not yet heard the news. Haven’t you heard? Gradualism is dead. That affects everything.

When you see how the uneven effects of emissions from capitalist states team up with other planetary amplifiers with degrees of autonomy of their own, the question becomes: How to generate a cross-regional pluralist assemblage of constituencies who come to terms with the Anthropocene and press regions, states, churches, universities, corporations, consumers, investment firms, and retirement funds to make radical changes over a short period of time. You must move on multiple fronts to both tame and redirect capitalist growth, as you look forward to a time when the perverse growth machine is brought under more severe control. So, what I mean by the “politics of swarming” does speak to the kinds of things we were just discussing.

The politics of swarming moves on multiple scales, going back and forth to amplify each in relation to the others. One register involves experimenting with role assignments that we pursue in daily life. It’s related to what Foucault meant by the “specific intellectual,” but is now extended to what might be called “specific citizens”. If, say, you are relatively well off in a high emitting regime you change the kind of car you drive, the occasions you ride a bike, the ways you press a neighborhood association to take action with respect to ecological issues, the way in which—if you are a teacher as we both are—you change your courses to highlight these issues, and so forth. You alter a series of role definitions, connecting to people and institutions in new ways. Some collective effects are generated here. But, the key point is how creative role experiments work on the visceral registers of cultural pre-understandings, perception, judgment, and relationality. They move them. They thus prepare us to take new actions in other domains. We, in effect, work tactically upon our relational selves to open them to new contacts and to insulate them from Trumpian rhetoric.

Now other scales of politics can be engaged in a new key: protests, boycotts, electoral politics, creating eco-sanctuaries, copying tactics that have worked in other regions. As the activities escalate and as we encounter new events—a rapidly escalating glacier melt, a new upsurge of climate refugees, vigilante actions against climate activists, etc.—it may now be possible to forge a cross-regional assemblage, applying new pressure from the inside and outside upon states, corporations, churches, universities, temples, neighborhoods, and elected officials to take radical action. A politics of swarming acts at many sites at once.

These cross regional assemblages may not be that likely to emerge, of course. But in the contemporary condition it becomes a piece of crackpot realism to say, “OK, let’s forget it then”. For the urgency of time makes it essential to probe actions that may be possible in relation to needs of the day. The politics of swarming could perhaps crystallize into cross-regional general strikes, as constituencies inspire each other into peaceful and urgent modes of action. A cross regional strike is what I call an “improbable necessity” because the situation is more stark than those imagine who have ignored the history of planetary volatility before the advent of Anthropocene. They overlook how planetary gradualism was never true and is not true now; hence they miss the autonomous role volatile planetary forces play now as C0 2 emissions trigger amplifiers that generate results greatly exceeding the force of the triggers. By “swarming” I mean action on multiple fronts across several constituencies and regions that speak to the urgency and scope of the issues we face. Since we have seen several times in the past how capitalism can be stretched and turned in new directions as well as how imbricated it is with a series of forces that exceed it, the interim task is to stretch it now and then to see how to tame further the growth imperatives it secretes.

The Power of Myth

Nidesh Lawtoo: Facing the Planetary starts with a myth, and although the book itself is not about fascism but about self-regulating planetary processes, the question of myth is also relevant to our discussion for it is genealogically related to fascism. Myth was, in fact, appropriated by Fascists and Nazis alike to celebrate a racist, anti-Semitic ideology. I’m thinking in particular of Alfred Rosenberg’s The Myth of the 20th Century, which was not as influential as Hitler’s Mein Kampf but was nonetheless one of the bestsellers of the Third Reich. Addressing a distressed, disappointed and suffering population in the aftermath of the Great War going through a severe economic crisis, Rosenberg articulated the ideology of Nazism by promoting the Aryan racial myth and the necessary to root the German Volk back in an essentialist and nationalist conception of “blood and soil.” Much of what we’ve just said about rhetoric equally applies to the power of myth to move the masses on a visceral/mimetic register, and precisely for this reason, political theorists, starting very early, all the way back to Plato, have tended to be critical of myth and set out to oppose, or even exclude, the mythic, along with the affective registers it mediates.

Interestingly however, even Plato in his articulation of the ideal republic, cannot avoid the mythic. In his critique of Homer or Hesiod, in the early books, and throughout Republic as well as other dialogues, he relies on mythic elements, such as characters, dialogues, allegories, gods, heroes, and so forth. Somewhere in Laws he even says that this ideal polity has been constructed as a “dramatization of a noble and perfect lie,” or myth. There is thus a sense in which Plato opposes myth via myth, or relies on a philosophical register that includes the mythic to discredit mythic fictions as lies far removed from the truth. Of course, you work within a very different, actually opposed, political ontology, one based on becoming over Being, immanence rather than transcendence, horizontality much more than verticality. Still, one could detect a similar strategic move in your appropriation of the myth from the Book of Job that prefaces Facing the Planetary, in the sense that you rely on a tradition which has in Nietzsche (who was a critical but careful reader of Plato) a major modern representative and considers that in the mythic, past and present theorists, can find a source of inspiration that can be used to counter some of the forces we have been grouping under the rubric of fascism or new fascism.

To return to the opening pages of Facing the Planetary: you show how the Nameless One in the Book of Job attunes Job to nonhuman, planetary forces (oceans, clouds, tornados, etc.), and at one remove, your book relies on this myth to render us attentive to a volatile world of multiple forces as well, as we slide deeper into the Anthropocene. For the present discussion, I wonder if you could draw upon this view of myth open to a plurality of planetary forces to address or counter the myths at play in the politics of (new) fascism. Just as visceral affects can be put to fascist and anti-fascist uses, could myth become a source of inspiration for countering fascist myths?

Bill Connolly: I agree. What I can say is, yes, Plato said that he opposed the mythic, but then in the Symposium he offers a counter-myth of ascending to a transcendent level at which you gain an intuitive grasp of the Forms—it’s an intuitive grasp. He knows that he can’t simply prove such an ascension, then; rather, he produces a myth to support the possibility. But his myth is different from some he opposes because it arises out of a dialogue in which characters pose questions about it, continue to have doubts about it, and so on. Aristophanes is never convinced. So, it’s not just one myth vs another; this mythic mode is sprinkled with reflective dimensions; and that’s true of Nietzsche as well.

You take Alfred Rosenberg, whom you know better than I do. I will take Hitler. Hitler also focuses on the centrality of a racial myth. He saw one day, according to his testimony in Mein Kampf, how Jews provided the “red thread” tying everything he hated together: he could tie them to social democracy, to communism, to miscegenation, to shopkeepers and to other things he wanted to oppose. He presents the racial myth of the Aryan people as an authoritative myth that must be accepted; he terrorized everyone on the other side of it: Jews, homosexuals, Romani, social democrats, and others who resisted its “truth”. Today he would call its opponents purveyors of Fake News.

When I present in the Preface of Facing the Planetary a discussion of the Book of Job as a myth, I draw upon the testimonial in the Theophany in which the Nameless One speaks to Job out of a whirlwind or tornado. Job thus allows us to see and feel how our dominant spiritual traditions include some characterizations of planetary processes and nonhuman beings that are neither oriented to human mastery nor expressive of a world organically predisposed to us. Neither-nor. The world is worthy of embrace despite that in part because it enables us to be. The new work in the earth sciences on planetary processes encourages us to think anew with and through such an orientation, to respect a planet with periodic volatilities, replete with multiple trajectories that intersect and exceed our capacities to master; a planet that will not even become that smooth and slow if we start now to tread lightly upon it. There are strong premonitions of such an image in the Book of Job. You can hear them also elsewhere, as Bruno Latour has shown with his reading of Gaia, the volatile image of the planet developed from Hesiod. And so, we can sometimes engage myths to jostle dangerous assumptions and demands settled into the background of our thinking, practices, theories, and activities, opening them up for new reflection. Because there is never a vacuum on the visceral register of cultural life there are always background premonitions that in-form life. They need to be jostled on occasion. The Anthropocene is a new era, but the rapid shifts it portends are not unique. It is only recently that capitalism has become the key catalyzing agent of planetary change—in dynamic relation to other volatile forces.

Nietzsche was right to say that myth, as a condensation of cultural preunderstandings and insistences, works on the visceral register of being in its modes of presentation, its rhythms of expression, and so forth. I agree with you that we are never in a world in which there is not some kind of mythic background sliding into preunderstandings, modes of perception, and prejudgments. The mythic is not to be eliminated; it is, rather, to be approached much differently than Hitler or Rosenberg approached it, along at least two dimensions: you resist and challenge the myth of the racial Volk, challenging both its falsity and the visceral hatreds that fuel support for it; you then jostle the reassuring myth of planetary gradualism with counter-understandings of planetary processes.

I do not want to eliminate the mythic, and I’m guessing that Plato, whom you have studied more deeply, did not want to either. You could also take an early-modern thinker such as Hobbes who tells you to get rid of rhetorical figures and mythic arguments. Then you read Hobbes carefully and realize he is a rhetorical genius and knows himself to be one. The mythic never disappears: you can draw upon it to disturb and shake cultural predispositions about the planet that continue to hover in the background of the thinking, spirituality and demands of so many people in old capitalist states. At least the Book of Jobhelps to loosen up undergrads in my classes as they encounter again a childhood story they thought they had already engaged. That’s the way I’m trying to think about it.

Mimesis, Tyranny, Strikes

Nidesh Lawtoo: Your interest in the mythic and the way it operates on what you call the visceral register resonates very much with what I call the mimetic dimension of human beings, or Homo mimeticus. I mean by that the fundamental biological, psychological, anthropological, and, since the discovery of mirror neurons, neurological fact that we are, nolens volens, imitative animals that respond, emotionally, affectively, and often unconsciously to the stories we are told, including, of course, political stories. And these stories, as Plato, Nietzsche and many others saw, are not simply imitations of reality, or representations—stable, realistic images we can see from a safe distance. Rather they have a destabilizing formative and transformative power—Nietzsche also calls it a pathos—that spills over the wall of representation to affect and infect, by visceral contagion, our psychic and political lives as well. Mimesis as an unconscious or semi-conscious imitative pathos triggered by what we see and, above all, feel.

To move toward a conclusion and establish a genealogical bridge with other thinkers who are currently countering the rise of neo-fascist movements, I would like you to briefly comment on a recent book that, in many ways, resonates with our discussion: Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century (2017). In this little but illuminating book, Snyder, who is an American historian specialized on the history of the Holocaust, seems to share the presupposition with which we started: namely, that it is necessary to learn from the strategies mobilized by fascist and Nazi leaders and ideologues in the 1930s, and 40s in order to steer contemporary constituencies away from the political reenactment of those horrifying possibilities.

To that end, Snyder offers a series of practical, action-oriented suggestions that structure the book and help us counter the rise of fascism, suggestions like “Do Not Obey in Advance,” or “Defend Institutions,” or “Believe in Truth.” He offers twenty of them, but I would like to zoom in on Lesson 8 titled, “Stand Out,” for it seems in line with a principle necessary to develop what you call “politics of swarming” and addresses forces that I call “mimetic.” Snyder writes: “Some has to. It is easy to follow along. It can feel strange to do or say something different. But without that unease, there is no freedom. Remember Rosa Parks. The moment you set an example, the spell of the status quo is broken and others will follow.” There is a double movement at play in this passage that retraces, from the angle of mimesis, your double-take on rhetoric and myth, in the sense that anti-mimetic movements (not following along) can generate alternative models (or examples) on which the politics of swarming hinges that, in turn, have the potential to trigger mimetic counter-movements (others will follow). Can you comment on this lesson? And what additional lessons emerged from your genealogy of fascism that we could add to the list?

Bill Connolly: I read Snyder’s book last winter, maybe in January, as I was thinking about using it in the seminar on Fascism. We didn’t end up using it—there is the problem that you have forty books on the list and you end up using only ten—but I was impressed with Snyder’s book for several reasons, the most important being its timeliness and its courageousness. He says: We are in trouble; things are going in the wrong direction; don’t think this is just a little blip on the horizon that will automatically disappear—and I agree with him on that. I also liked the way the book is organized around twenty recipes of response. The one that you call attention to, “do not obey in advance,” that is, resist tacitly going along to get along. I think of that as congruent with the themes of role experimentations mentioned earlier. Role experiments create room within the things that you regularly do, like work, raising kids, attending church, relating to neighbors, writing, retirement investments, teaching, etc. You then take a step here, a step there, outside settled expectations, because there is often room to do things that exceed merely going along to get along. They make a difference in a cumulative effect, yes. But the most important effect is the way they help to recode our tacit presumptions and orientations to collective action. Even small things. In this spirit, I recently used Facebook to write an open letter to Donald Trump after he withdrew from the Paris Accord. Making such a minor public statement can coalesce with innumerable others doing similar things. People shared it; it received a broader hearing; even some trolls ridiculed it. It would not be easy to take back. The accumulation of such minor actions counters the scary drive to allow Trumpism to become normalized. Charles Blow, the New York Times columnist, also keeps us focused on that issue.

I like several things about Snyder’s book, but I think—maybe I am wrong for I might not have read it carefully enough—that it is kind of limited to what you and I, as individuals and small groups, can do. Today we need to join these small acts to the larger politics of swarming, out of which new cross regional citizen assemblages grow. Such assemblages themselves, in the ways they coalesce and operate horizontally, expose fallacies in the fascist leadership principle. Protests at town meetings, for instance, fit Snyder’s theme, I am sure. But let’s suppose, as could well happen, that the Antarctic glacier starts melting at such a rapid rate we see how its consequences are going to be extremely severe over a short period of time. (The computer models are usually three to five years behind what actually happens on the ice, ground, and atmosphere). Constituencies in several regions could now mobilize around this event to organize general strikes, putting pressure on states and corporations from inside and outside at the same time. So, the main way I would supplement Snyder is to explore the horizontal mobilization of larger assemblages, to speak to the urgency of time during a period when dominant states so far resist doing enough.

Further, from my point of view, electoral politics poses severe problems; but there is also a dilemma of electoral politics that must be engaged honestly. Electoral victories can be stymied by many forces. But you must not use that fact as a reason to desist. For, as some of us have argued on the blog The Contemporary Condition for several years, if and when the right wing gains control of all branches of government you run the severe risk of a Fascist takeover. So, participate in elections and act on other fronts as well. Indeed, in the United States the evangelical/capitalist resonance machine has acted in its way on multiple fronts simultaneously for decades. The Right believes in its version of the politics of swarming.

The way to respond to the dilemma of electoral politics is to expand beyond it but not to eliminate it as one site of activity. For, again, if the right-wing controls the courts, the presidency, both houses of Congress, the intelligence agencies, and a lot of state legislators, they can generate cumulative effects that will be very difficult to reverse. Aspirational Fascists, for instance, use such victories to suppress minority voting. So, multiple modes and registers of politics.. I wouldn’t be surprised if Snyder and I agree on that.

Aspirational Fascism

Nidesh Lawtoo: I think you’re right that you two would agree. In Snyder’s longer genealogy of fascism and Nazism, Black Earth, of which the little book is in many ways a distillation, he ends with a chapter titled “Our World,” which situates fascist politics in the broader context of climate change and collective catastrophes along the lines you also suggested in Facing the Planetary. The more voices promoting pluralist assemblages contra the nihilism of fascist crowds, the better!

Speaking of little books, then, I hear you are yourself working a on a new short book dealing with some of the issues we have been discussing, which is provisionally titled, Aspirational Fascism. To conclude, could you briefly delineate its general content, scope, and some of the main lessons you hope will be retained.

Bill Connolly: This will be a short, quickly executed book, a pamphlet, that could come out within a year. It’s divided into three chapters, and it will probably be around 100 pages. The first chapter reviews similarities and differences between Hitler’s rhetoric and crowd management and those of Donald Trump. It also attends to how the pluralizing Left has too often ignored the real grievances of the white working class, helping inadvertently to set it up for a Trump takeover. The second chapter explores how a set of severe bodily drills and disciplines in pre-Nazi Germany helped to create men particularly attuned to Hitler’s rhetoric in the wake of the loss of WWI and the Great Depression. You and I are having this conversation today in Weimar, a sweet, lovely, artistic town. Hitler, I am told, gave over 20 speeches here, in the Central platz, to assembled throngs.

So, in the second chapter I attend to how coarse rhetorical strategies, severe bodily practices, and extreme events work back and forth on each other. That chapter is indebted to a book by Klaus Theweleit, Male Fantasies (1987, 2 vols.); it helps me to attend to how specific bodily disciplines and drills attune people to particular rhetorical practices and insulate them from others. The themes Theweleit pursues are then carried into the United States of today as we explore how the neglect of real white working class grievances, the military training and job disciplines many in that class face, and the interminable Trump campaign work back and forth upon one another. That is why I never understate the need to attend to our own bodily disciplines, habits, and role practices.

The third chapter is designed to show how what I call multifaceted pluralism is both good in itself and generates the best mode of resistance to Fascist movements. Multifaceted means that it supports generous, responsive modes of affective communications and bodily interrelations; it also means that the new pluralism treats the white working class to be one of the minorities to nourish, even as we also oppose the ugly things a portion of it does. That support must first include folding egalitarian projects into those noble drives to pluralization that have been in play; it must also include taking radical action to respond to the Anthropocene before it generates so much ocean acidification, expansive drought, ocean rising, and increasing temperatures that the resulting wars and refugee pressures will provide even more happy hunting grounds for aspirational Fascism.

The pluralizing left must come to terms immediately with the need to ameliorate class inequality in job conditions, retirement security, and workplace authority. That deserves as much attention as the politics of pluralization itself. I pursue a model of egalitarian pluralism, then, that challenges both liberal individualism and the image of a smooth communist future, seeing both to be insufficient to the twin dangers of Fascism and the Anthropocene today. There are no smooth ideals to pursue on this rocky planet. But there may be ways to enhance our attachment to a planet that exceeds the contending adventures of mastery that dominated the 19th and 20th centuries.

Those are the three parts of the book. I realize, for sure, that the project makes for heavy lifting, that it will be difficult to convince some pluralists to push an egalitarian agenda and some segments of the working class to take the Anthropocene seriously. But the two projects are interrelated and imperative, and it is possible that advances on the first front could loosen more people up to accept action on the second.

Nidesh Lawtoo: I look forward to this new book. I think that your work, which speaks not only to academics and students across disciplines but also to the general public, including the working-class constituencies we have been addressing, demonstrates, among many things, the importance of the general strike that you call and “improbable necessity.” In the wake of the cumulative scandalous political actions—the last to date being the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement—that do not simply repeat European fascism but entangle new fascist power with nonhuman planetary forces in such catastrophic ways, I’m even tempted to think, or hope, that a vital improbability will, in the near future, turn into an emerging, perhaps even probable possibility. Be that as it may, I thank you for the richness of your work and for the inspiring vitalism you affirm.

Bill Connolly: It has been an illuminating conversation for me. Thank you.

Weimar, 9 June 2017

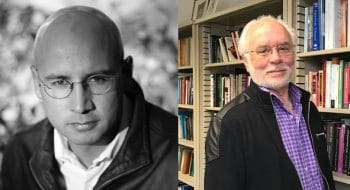

Nidesh Lawtoo is Assistant Professor, ERC Principal Investigator, Department of English, University of Bern.

William Connolly is Krieger-Eisenhower Professor, Johns Hopkins University.