Where do you see the most exciting research and debates occurring in your field?

As a writer and a journalist with an enduring interest in understanding India, I find the Economic & Political Weekly, Social Scientist, and Aspects of India’s Economy among the most illuminating. All three have been edited by dedicated left intellectuals and run on shoestring budgets, and have a desire to reach left activists. I generally find social-science journals by academics and for academics difficult to follow. I mostly work in a Marxian paradigm. For serious Marxist analyses and debates that adhere to accepted theoretical and empirical scientific standards and are presented in a readily intelligible form, there’s nothing better than Monthly Review, the “independent socialist magazine” published from New York City.

How has the way you understand the world changed over time, and what (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking?

My understanding of the world owes a lot to the writings of Paul A Baran and Paul M. Sweezy, the founders of what may be called the Monthly Review School, and Harry Magdoff and Samir Amin, other important figures of that way of looking at and reacting to the world. Of course, even as Marxist intellectuals share a way of looking at and reacting to the world, they differ in many matters of interpreting and evaluating it. The Monthly Review School’s distinctive intellectual structure took shape with Baran’s The Political Economy of Growth (1957), Baran and Sweezy’s Monopoly Capital (1966), and Harry Magdoff’s The Age of Imperialism (1969), and like the best of all social science, it has been subject to change with the advance of knowledge and understanding. Within this scientific tradition, more recently, John Bellamy Foster has incorporated an ecological Marxist analysis that goes back to Marx in its theoretical construction.

My comprehension of the world owes a lot to what may be called (that part of) the dependency tradition that emanated from Baran’s The Political Economy of Growth, which advanced propositions such as the “development of underdevelopment” (made famous by Andre Gunder Frank), surplus extraction by the imperialist powers from the periphery, and revolution together with “delinking” (Samir Amin) from the economies of the imperialist powers as the way out of underdevelopment. In my case, there haven’t been any significant shifts in my thinking, if by “significant” one means a change of paradigm. But the emphasis has certainly changed—for example, in the present context of “outsourcing”, sub-contracting, “low-cost labour arbitraging” and super-exploitation of labour, one now emphasises the massive size of India’s “reserve army of labour” relative to its active army of wage labour, which has its roots in the process of de(proto)industrialization in the 19th century.

Fidel Castro, who passed away in November 2016, famously declared that history would absolve him. What is the legacy of Castro in the Global South, and do you believe that history has absolved him?

I am trying to picture Fidel Castro on September 21, 1953 in a courthouse at Santiago ending his defence plea thus: “Sentence me. I don’t mind. History will absolve me.” And, I’m trying to conceive of Fidel at the time of U.S. President Barack Obama’s visit to Cuba in March 2016 when, in his column “Reflections” in the Cuban media, this one entitled “Brother Obama” (which appeared on 28 March 2016), he wrote: “We do not need the Empire to give us any gifts.” His legacy in the Global South, in my view, is of a real colossus of 20th Century rebellion against U.S. imperialism.

Regarding your question about whether “history has absolved him,” who am I to judge? From a U.S. neo-colony where one out of every four persons 10 years of age and above could not read or write, and where many starving children infected with parasitic worms died for lack of medical facilities/attention, to a liberated country whose literacy levels are higher and infant mortality rate lower than that of the U.S. itself is, no doubt, a remarkable achievement. And, Cuban internationalism—its medical missions have been appreciated by the poor and the needy not only in countries like Haiti, Brazil and Venezuela, but even in those of West Africa when they were badly affected by the Ebola virus, and also the south Pacific. But history has also come with many setbacks, given the strength and the ruthlessness of the counterrevolution that the revolution was confronted with, and many mistakes were made by the revolutionists, for instance, in the violation of civil liberties. History certainly doesn’t come easy.

In 2006 India’s Prime Minister described the country’s Maoist movement as “the single largest internal security threat” that his government faced. Ten years on, should the Maoists still be seen as a significant force in Indian politics, and does their strategy of protracted people’s war (PPW) have any hope of succeeding in a 21st century context?

Repressive governments invariably exaggerate the external and internal “security threats” they face, this in order to justify higher and ever more allocations of funds for the repressive apparatuses of the state. The Maoists have, since May 1967 always been a significant force in Indian politics because—unlike the parliamentary political parties that represent the interests of factions within the ruling classes and use electoral politics to settle differences within the ruling classes—they have been organising the masses for revolution aimed at overthrowing the existing social order.

The Maoist strategy of protracted people’s war (PPW) involves the political mobilization of (mainly) poor, including tribal, peasants in the creation of a people’s guerrilla army; the building of “base areas” where miniature New Democratic governments are sought to be established; the use of the countryside in the transition from guerrilla to mobile warfare; and the encircling and winning over of the cities to finally capture power. The Maoists have however not yet been able to establish “base areas” where they can demonstrate the qualitative superiority of their brand of “mass-line” (“from the masses, to the masses”) politics over the establishment’s discredited and corrupt form of liberal-political democracy. Equally important, the creation of base areas is essential for the sustainability of the PPW—in guerrilla parlance, the base areas are the Maoist guerrilla army’s essential “rear.” In the absence of base areas, the guerrilla army will not last long or grow and spread.

The Nepali Maoists role in overthrowing the country’s monarchy and subsequently entering government was described by Samir Amin in 2009 as “the most radical revolutionary advance of our epoch”, yet since this point the movement has fragmented and fallen out of power. What are the key lessons of this experience, and what has the impact been on other Maoist movements across South Asia?

Certainly, the Nepali Maoists had made a “promising revolutionary advance,” as Samir Amin put it. They had advanced up to the penultimate stage in the protracted people’s war, but, I think, they neither had the military strength (relative to the then Royal Nepal Army) nor the required urban, mass popular support to encircle and win over the district headquarters and the Kathmandu Valley. So in 2006 they went in for a joint (with the seven parliamentary parties) urban mobilization against the autocratic monarchy. But, sensing the impending collapse of the monarchy, New Delhi and Washington coordinated the counterrevolutionary strategy to bring the Nepali revolution to a close. Even as the Maoists came out on top in the 2008 elections and entered the establishment’s power structure, they couldn’t advance any of the objectives they were expected to—radical land reform, fusion of the two armed forces in a dignified manner, going beyond liberal-political democracy in the direction of “people’s democracy,” genuine federalism, and scrapping the 1950 Nepal–India treaty and the 1965 bilateral security pact.

But yes, the Maoists must be given their due—it was mainly due to their efforts that the monarchy was abolished and the republic came into being, and the Constituent Assembly was convened. Setbacks on the road to revolution however led to recrimination and a split in the Maoist party resulting in a division of both the social and electoral constituencies of the Maoists, and consequent electoral setback for the UCPN(Maoist), followed by further fragmentation. There are two main lessons one can learn from this whole experience—one, that while tactical flexibility is a must, this must never be at the cost of undermining the very strategy itself; and two, no ruling class and the sub-imperialist power (in Nepal’s case, India) backing it ever give up their interests, influence, power, privilege, and wealth without using all possible means at their disposal to defend and consolidate their rule. When the Nepali Maoist movement, rooted in the material conditions of exploitation in Nepal and aimed at overthrowing the exploitative and oppressive social order there, suffered a setback, it certainly adversely affected the South Asian organisation of Maoist parties and movements—the Coordination Committee of Maoist Parties and Organizations of South Asia (CCMPOSA).

Given the poverty and social ills which persist across much of Indian society, do you think that it is accurate to describe India as an ‘emerging power’?

Well, a principal characteristic of Indian society is its monstrous inequality, of which mass poverty is an integral part. But, so is the extreme concentration of wealth and power, and one therefore has to take account of the ingredients of power of the Indian state—nuclear warheads, intermediate-range ballistic missiles, a civil nuclear cooperation agreement with the United States, impending entry to the dual-purpose nuclear technology control regimes (e.g. Nuclear Suppliers’ Group), and the country’s naval reach, in alliance with the U.S. and Japanese navies, around the Indian Ocean to the South China and East China Seas. Indeed, following the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA) with the US, the ground has been laid for the Indian and U.S. militaries to work closely together, allowing the use of their respective bases for refuelling, maintenance, replenishment of supplies, etc. And, with Washington’s recognition of New Delhi as a “Major Defence Partner,” this is supposed to facilitate the US’ “technology sharing with India to a level commensurate with that of its closest allies and partners”, including “license-free access to a wide range of dual-use technologies”, “support of India’s Make in India initiative, and to support the development of robust defence industries and their integration into the global supply chain…” (The matter within quotes is official speak).

In the process of advancing their power, their influence and their mutual interests beyond the country’s borders, the Indian state and Indian big business are dependent upon U.S. imperialism with which New Delhi has forged a strategic alliance as a junior partner. Will this eventually lead to India’s emergence as a sub-imperialist power in South Asia? As of now, only Bhutan seems to have accepted India’s authority, certainly not Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Pakistan or Sri Lanka, or even Nepal or the Maldives, but as a sub-imperialist power backed by Washington, some of these South Asian countries may be expected to fall in line.

If India is “crying out for revolutionary change” then who will be the agents of this revolution and what are the main obstacles that they will need to overcome?

From the time of independence in 1947, India has had the resources and the potential to achieve a high level of human development—yet the great majority of the country’s people have remained desperately poor. Tragically, India remains among the most poverty-stricken countries of the world, with most of the population still inadequately fed, miserably clothed, wretchedly housed, poorly educated, and without access to decent medical care. Hundreds of millions have been the victims of Indian capitalism’s irrationality, brutality, and inhumanity. It is no wonder that for fifty years, the one persistent message of the nation’s Maoists, the Naxalites, has been that India’s deeply oppressive and exploitative social order is “crying out for revolutionary change.” To your question as to “who will be the agents of this revolution,” they will be the oppressed and exploited peasants, including the tribal peasantry, highly exploited workers, and the urban poor who earn a living in the informal sector, all led by a revolutionary intelligentsia drawn from the educated middle class.

The “main obstacles that they will need to overcome” are (i) the caste system, which is fundamentally antithetical to any meaningful unity of the exploited and the oppressed; (ii) religion, ethnicity and nationality, all divisive cards played by the main political parties to divide the toiling masses; and (iii), the inability, so far, to get the soldiers and the police to be unwilling to use force against their fellow citizens, as happened during the French and Russian revolutions. Regarding (iii), it is only when the soldiers and the police reckon that the oppressed and the exploited might win that they may join them. And, if the oppressed can be convinced that their “fate” is not the natural state of affairs, and if the revolutionaries succeed in creating among the oppressed a socialist perception of a better world and belief in the possibility of its attainment, then (i) and (ii) can be overcome.

Scholars such as William I. Robinson have posited that the formation of a transnational capitalist class and “thirdworldization” of sections of the population in the Global North means that traditional theories of imperialism are now defunct. Is the concept of imperialism still viable, and if so, what do you see as its key tenets?

I must say I usually look forward to reading anything by William I. Robinson on Latin America that I can lay my hands on. But I think that his postulations of a “transnational capitalist class” and a “transnational state” implying that national bourgeoisies and the nation-states are tending to be insignificant are gross (theoretical) exaggerations. It is a bit strange that precisely when some of the classic features of imperialism remain, albeit in significantly modified forms (monopoly-finance capital; the tendency to stagnation; waves of mergers & acquisitions, including cross-border ones; huge monopoly profits and capital gains; export of capital and extraction of economic surpluses from the exploitation of cheap labour in the periphery; geopolitical rivalry; nation states and their big corporations coming together to advance their power, their influence, and their mutual interests beyond their borders; natural resource grabs; more neo-colonies and dependencies with the East having joined the South) and others are manifesting themselves in naked forms (direct military intervention; indirect military manoeuvres; a vast network of U.S. military bases; the spread of NATO’s tentacles; strategies to monopolize weapons of mass destruction), that some scholars are claiming that imperialism is no longer a meaningful category.

Of course, a small section of the periphery’s capitalists have also been able to appropriate significant shares of the monopoly profits to become dollar billionaires; a few of the independent countries subordinated to the imperialist powers have become sub-imperialist; the World Bank, the IMF, and the WTO have been advancing the interests of the developed capitalist countries rather than endeavouring to overcome underdevelopment in the periphery; and the “collective imperialism of the Triad” (the US, the main Western European powers, and Japan) led by the United States seeks to jointly manage the world. I haven’t come across anything so profound about the capitalist process of imperialism over the long-term as is captured in this quote from Harry Magdoff (“Globalization: To What End?,” Monthly Review, 43:9, February 1992, p. 3): “Centrifugal and centripetal forces have always coexisted at the very core of the capitalist process, with sometimes one and sometimes the other predominating. As a result, periods of peace and harmony have alternated with periods of discord and violence. Generally, the mechanism of this alternation involves both economic and military forms of struggle, with the strongest power emerging victorious and enforcing acquiescence on the losers. But uneven development soon takes over, and a period of renewed struggle for hegemony emerges.”

While there were clearly many reasons to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Economic and Political Weekly in 2016, recent times have been quite turbulent for the Journal, with the resignation of two Editors coming in relatively quick succession (January 2016 and July 2017). As Deputy Editor of EPW, what have been your proudest achievements, and what are your hopes for the Journal over the coming years?

All the EPW’s achievements as regards the content are the result of the collective endeavours of the editorial team and our writers—producing a combination of a current affairs magazine and an interdisciplinary social-science journal week after week; coming out with special sections in a few of the weekly issues, for instance, “China after 1978,” “Global Economic & Financial Crisis,” “Naxalbari and After” on the 50th anniversary of Naxalbari, and this month, “Das Kapital, Volume 1—150 years,” and in November, “The Russian Revolution and Socialism.” As regards my hopes for the future of the EPW, besides continuing to do what I have just mentioned, I wish (I am due to retire at the end of the year) the magazine also scouts for and publishes factually accurate investigative accounts exposing intertwined corporate fraud and political corruption. The present phase of neo-Robber Baron capitalist development in India needs to be carefully documented and presented to the public.

What is the most important advice you could give to young scholars and editors working in the fields of political economy and international relations?

Impart the truth without fear or favour, based on a sense of authentic history; stand by the scientific method; always maintain a questioning and critical attitude towards the world at large.

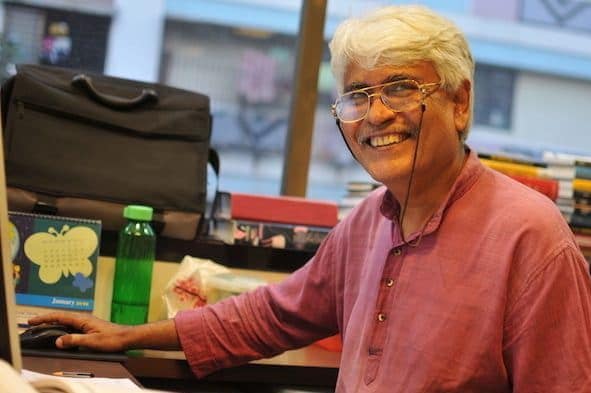

Bernard D’Mello is a senior journalist with the Economic & Political Weekly and a civil-liberties activist with the Committee for the Protection of Democratic Rights, Mumbai. His works include What is Maoism and Other Essays (Cornerstone Publications, 2010) and India after Naxalbari (Monthly Review Press, forthcoming).

Laurence Goodchild is Deputy Features Editor at E-IR.